[ad_1]

Like natural evaporative air conditioners, forests directly cool the planet. What happens if you take them down?

Rapid deforestation occurs in tropical countries like Brazil, Indonesia, or the Congo. may have accounted forUp to 75% of surface warming observed between 1950 and 2010 can be attributed to this factor Our new researchWe took a closer look at the phenomenon.

Using satellite data over Indonesia, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea, we found deforestation can heat a local area by as much as 4.5℃, and can even raise temperatures in undisturbed forests up to 6km away.

More than 40% of the world’s population live in the tropics and, under climate change, rising heat and humidity could push them into lethal conditions. It is essential to preserve forests in order to protect the people who live within them and those around them as the planet heats.

Shutterstock

Hot spots for deforestation

At the recent climate change summit in Glasgow, world leaders representing 85% of Earth’s remaining forests committed to ending, and reversing, deforestation by 2030.

This is a crucial measure in our fight to stop the planet warming beyond the internationally agreed limit of 1.5℃, because forests store vast amounts of carbon. Deforestation releases this carbon – approximately 5.2 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide per year – back into the atmosphere. This account accounts for nearly 10% global emissions between 2009-2016.

Deforestation is particularly prevalentIn Southeast Asia We calculateBetween 2000 and 2019, Indonesia lost 17% (26.8million hectares) of its forested land, and Malaysia 28% (8.12million hectares) of its forest cover. Others in the region, such as Papua New Guinea, are considered “deforestation hot spots”, as they’re at high risk of losing their forest cover in the coming decade.

For a variety reasons, forests in this region are being cut down, including to expand palm oil and timber plantations and logging, mining, and small-scale farms.

These new land uses can result in different spatial patterns for forest loss. Satellites can measure and see these spatial patterns.

EPA/HOTLI SIMANJUNTAK

What we found

We already know that forests have a direct effect on climate change. Losing forest can cause local temperatures to rise. We wanted to see if different patterns in forest loss affected how much temperature increased and how far warming spread into neighboring, unaltered areas.

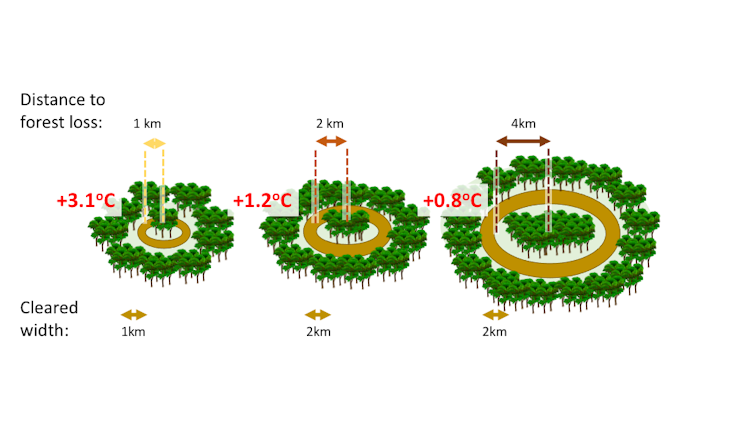

To find out more, we usedSatellite images that measure temperature at the land surface. As shown in the illustration below, we calculated this by averaging the forest loss in rings of different widths. We also looked at the average temperature change within each ring.

For example, if you consider a circle of forest that’s 4km wide, and there’s a completely deforested, 2km-wide ring around it, the inner circle would warm on average by 1.2℃.

The greater the forest loss, it is, the more warming. If the ring was 1-2km away, the circle would warm by 3.1℃, while at 4-6km away, it’s 0.75℃.

These may not sound like large temperature increases, but global studies prove otherwise. for each 1℃ increase in temperatureThis would result in a decline of around 3-7% in major crops’ yields. Southeast Asia’s forests can be preserved within 1km of the agricultural land to prevent crop losses of 10-20%.

These estimates are conservative as we only measured the effects of forest loss on average annual temperatures. Another important factor is the fact that average temperatures are higher. usually createTemperature extremes that are higher, like heatwaves, are more dangerous. The heatwaves with extremely high temperatures are the most dangerous for crops and people.

Of course, forests aren’t normally cut down in rings. This analysis was done to exclude other causes of temperature changes, and put the effect of non-local forest destruction in focus.

Why is this happening?

Forests cool the ground because trees draw water out of the soil to their roots, which then evaporate it. The heat and sunlight that evaporate water are the energy sources. This is why you feel colder when you step out of a pool of water on your skin.

A single tree in a rainforest can cause severe damage. local surface cooling equivalent to 70 kilowatt hours for every 100 litres of water used from the soil — as much cooling as two household air conditioners.

Because of their large canopies, forests are excellent at cooling the land. This is because they can evaporate a lot more water. This evaporative cooling stops in tropical regions, and the land surface heats up.

This is not new to Borneoans. In 2018, researchers surveyed people in 477 villages, and found they’re well aware nearby forest loss has caused them to live with hotter temperatures. When asked why forests were important for their health and the health their families, the most frequent answer was that trees regulate the temperature.

Aidenvironment, 2005/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

A double whammy in climate change

In many parts, including Australia and the Tropics, the expansion of farmland is a significant reason for reducing forest. Conserving forests may be a better strategy for food security, and the livelihoods of farmers, due to the fact that higher temperatures also reduce farm productivity.

If forests have to be cut, there are ways to prevent the worst temperature increases. For example, we found that keeping at least 10% of forest cover helped reduce the associated warming by an average of 0.2℃.

Similar results were seen for smaller areas of forest loss. Temperatures did not rise as much. This means that temperature impacts are less severe if deforestation happens in smaller, irregular blocks rather than all at once.

To share these findings, we’ve built a web mapping toolThis allows users to explore the effects of different patterns of forest loss on local temperatures throughout maritime South East Asia. It helps show why protecting forests in the tropics offers a climate change double whammy – lowering carbon dioxide emissions and local temperatures together.