[ad_1]

It must be difficult for Boris Johnson that he is a footnote in French. However, at the end of two very long weeks, there were only two outcomes at the UN climate summit at Glasgow. A Copenhagen-style meltdownPutting the implementation of Paris Agreement on hold for many years. Or a footnote.

A meltdown was never in anyone’s interest, so we have ended up with a footnote. A long footnote. An important footnote. But a footnote nonetheless. The Glasgow Climate Pact saw rules clarified, more finance, especially for adaptation, and greater clarity on long-term goals. loss and damageSome (still insufficient) progress was made on short-term commitments.

And if we step back and look at the decades-long process that started with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, it’s important, particularly for tired school-strikers, to realise how far we have come.

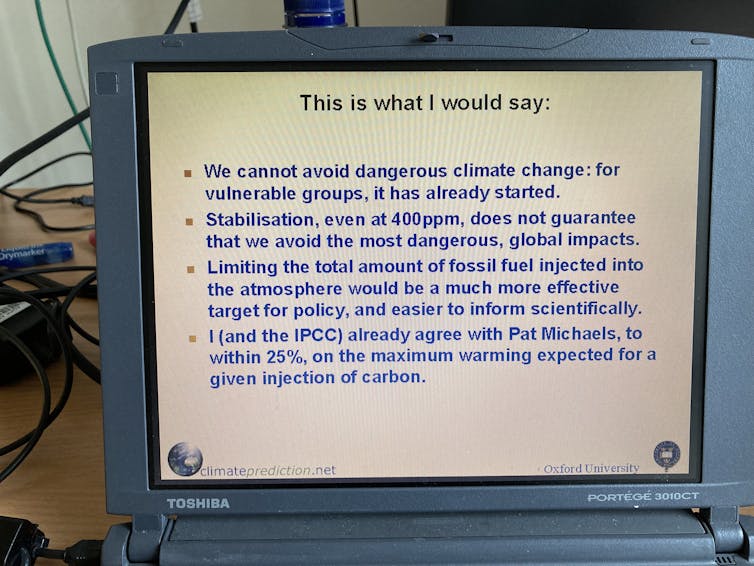

It took 16 years. 0.3℃) ago, in 2005, that my fellow-scientist Dave Frame and I gave a talk pointing out that the 1992 convention’s goal of stabilising atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases – which for carbon dioxide meant 50%-80% reductions in global emissions by 2100 – was unlikely to be enough to stop global warming. Warming was primarily determined by cumulative carbon dioxide emissions, so to halt warming we would need to reduce annual CO₂ emissions to net zero.

Myles Allen, Author provided

Later in 2005, we even gave a crude estimate of the “carbon budget”, or the amount we could dump in the atmosphere from burning fossil fuels over the entire industrial epoch before driving global temperatures over 2°C: one trillion tonnes of carbon, which is equivalent to 3.7 trillion tonnes of CO₂. The latest estimate combined historical and allowable emissions from the 2021 Global Carbon Budget is 3.74 trillion tonnes of CO₂.

To be fair, Dave and I were over-optimistic in that we didn’t account for carbon sinks weakening as soils warmForest fires are becoming more frequent. We thought just limiting fossil fuel emissions to that trillion tonnes would be enough for 2°C.

We fixed it all and published the result in 2009, along with several other groups drawing similar conclusions, it was clear we would have to limit all CO₂ emissions, including those from deforestation and not just from fossil fuels, to around a trillion tonnes of carbon to limit warming to 2°C. And that remains the estimate today – although we continue to eat into this total budget every year that emissions continue.

That wasn’t because these early groups were particularly clever or foresighted. It’s because the problem turned out to be simple. The best thing about studying how global temperatures react to greenhouse gas emissions has been how few surprises there have ever been. Global temperatures continue to rise decade after decade. predicted back in the late 1970s.

And the simplicity of that response must be a factor in how conversations at the UN’s annual climate summit have moved on. In 2003, when I attended COP10, I saw smartly dressed young Americans walking around in pairs, handing out leaflets that explained how coal was the future fuel and the lack of evidence for human influence.

The world has changed and I wonder how many of those young men (they were all male) were at COP26 as chief sustainability officers for major multi-national corporations or taking their daughters to Fridays For Future marches.

Our 2005 talk wasn’t particularly well received – “unhelpful” is the word I remember. This is perhaps unsurprising since the title of the conference was “Stabilisation 2005”, and we were grumbling that stabilisation targets were beside the point.

Cumulative emissions since pre-industrial had just passed half a trillion tonnes at the time, so people were concerned the message seemed to be: “Relax, we’re only half-way there.” Well, we’re now over two-thirds of the way.

Reasonable odds of 2°C

But if (and it’s a big if) countries manage to honour the pledges they’ve made since Paris, most importantly China’s declaration of carbon neutrality by 2060 and India’s net zero by 2070, even if serious global reductions don’t start until after 2030, we would (just) save the trillionth tonne of carbon.

This would give us, depending on what happens to other emissions, reasonable odds of limiting global warming to 2°C. Talking at COP18 Doha 2012 (the next COP where the idea of net Zero was still a bit radical), it was clear that I didn’t expect to be able in 2021 to write that.

Of course, it’s not enough, because while global temperatures have responded to emissions pretty much as expected, the climate impacts associated with even today’s level of warming, as we pass 1.2°C, have proved much worse than we would have predicted back in 2005. These were the unexpected surprises.

Nick_ Raille_07 / shutterstock

So the world decided in Paris in 2015 that 2°C was clearly not “safe”, and we should aim instead to limit warming to 1.5°C. That is where the Glasgow agreement falls short.

We have made progress in acknowledging where we want to get to, not how we’re going to get there, still less actual evidence we have started. Nations could only agree to “phase down”, not “phase out”, the use of unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies. That’s an agreement to slow, not stop.

At the very least, they agreed to mention fossil-fuels in a UN climate deal for the first. The industry is making new records at a moment when it is doing well. profitsIt must be brought in (kicking and screaming) to the tent to play its part. solutionIt should not be restricted to selling the product that is causing problems, nor should it be subsidised.

Early reductions are important because carbon dioxide builds up in the climate system. It’s just like the braking distance: the sooner you hit the brakes (slow global warming), the shorter your stopping distance (lower peak warming). And we don’t even know how well the brakes work.

The greatest uncertainty of all, and one they don’t talk about much in COP meetings, is that until we actually start to reduce global emissions, we won’t find out how hard – or easy – it will be. Transitions are often not as easy once we get started. expensive or traumatic as feared. We might be again surprised.