[ad_1]

It was one of the biggest climate change questions of the early 2000s: Had the planet’s rising fever stalled, even as humans pumped more heat-trapping gases into Earth’s atmosphere?

The scientific community was booming by the turn of this century. Climate change was understood on solid footing. Decades of research showed that carbon dioxide was accumulating in Earth’s atmosphere, thanks to human activities like burning fossil fuels and cutting down carbon-storing forests, and that global temperatures were rising as a result. But weather records seem to show that global heating slowed in the period 1998-2012. How could this be?

Scientists discovered that the apparent pause was a glitch in the data after careful analysis. The Earth had actually continued to warm. This hiccup prompted a large response from scientists and climate skeptics. This is a case study of how public perceptions can influence science, for better and worse.

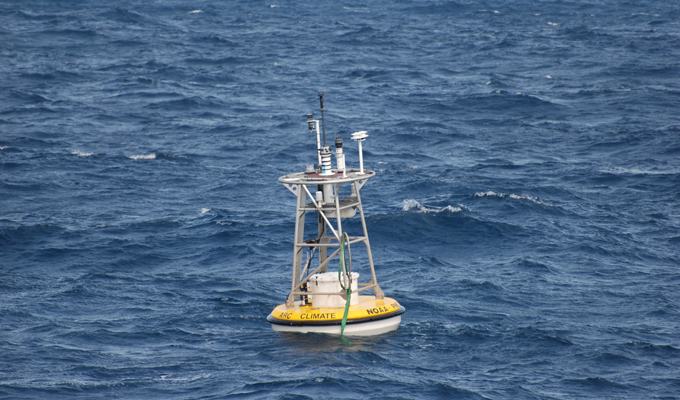

The mystery of what came to be called the “global warming hiatus” arose as scientists built up, year after year, data on the planet’s average surface temperature. Many organizations maintain their own temperature data. Each relies on observations from weather stations, ships, and buoys around globe. Although the actual amount of warming will vary from year to year and record-breaking years are becoming more common, overall, there is a trend upward. The 1995 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reportFor example, he pointed out that recent years had been amongst the warmest since 1861.

And then came the powerful El Niño of 1997–1998, a weather pattern that transferred large amounts of heat from the ocean into the atmosphere. The planet’s temperature soared as a result — but then, according to the weather records, it appeared to slacken dramatically. The global average surface temperatures rose between 1998-2012. It has fallen to half of the rate it did between 1951-2012. That didn’t make sense. As people add heat-trapping gas to the atmosphere at a faster rate, global warming should accelerate.

By the mid-2000s, climate skeptics had seized on the narrative that “global warming has stopped.” Most professional climate scientists were not studying the phenomenon, since most believed the apparent pause fell within the range of natural temperature variability. The public quickly noticed them and scientists began to investigate whether the pause was real. It was a highly publicized shift in scientific focus.

“In studying that anomalous period, we learned a lot of lessons about both the climate system and the scientific process,” says Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist now with the technology company Stripe.

Scientists were busy trying to understand why global temperature records seemed flat in the early 2010s. Ideas included the contribution of Cooling sulfur particles emitted from coal-burning power stationsAnd The Atlantic and Southern oceans absorb heat. These studies were the most concentrated attempt to understand the causes of year-to-year temperature variation. They revealed how much natural variability can be expected when factors such as a powerful El Niño are superimposed onto a long-term warming trend.

Scientists spent years investigating the purported warming pause — devoting more time and resources than they otherwise might have. Scientists began to joke about the journal’s publication of so many papers on the apparent pause. Nature Climate Changeshould be changed to Nature Hiatus.

Register for the latest from Science News

Summary and headlines of the latest Science NewsArticles delivered directly to your inbox

Thank you for signing-up!

We had trouble signing you up

In 2015, a team of researchers from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration published their findings. A jaw-dropping conclusion was reached in the journal Science. Global temperatures were not rising at a steady pace; rather, incomplete data had obscured the ongoing global warming. After more Arctic temperature records were added, and biases were corrected in ocean temperature data, the NOAA dataset showed that global warming was still continuing. The apparent pause of global warming disappeared when the corrected data was included. A 2017 studyHausfather, who led the study, confirmed and extended these results. Other reports.

Even after these studies had been published, the hiatus continued to be a favorite topic for climate skeptics. They used it as a way to argue that global warming is overblown. Congressman Lamar Smith, a Republican from Texas who chaired the House of Representatives’ science committee in the mid-2010s, was particularly incensed by the 2015 NOAA study. He demanded to see the data and accused NOAA of altering it. (The agency denied that the data had been altered.

“In retrospect, it is clear that we focused too much on the apparent hiatus,” Hausfather says. Figuring out why global temperature records seemed to plateau between 1998 and 2012 is important — but so is keeping a big-picture view of the broader understanding of climate change. The hiccup was a temporary fluctuation in an important and longer-lasting trend.

Science relies on testing hypotheses and questioning conclusions, but here’s a case where probing an anomaly was taken arguably too far. It caused researchers to doubt their conclusions and spend large amounts of time questioning their well-established methods, says Stephan Lewandowsky, a cognitive scientist at the University of Bristol who has studied climate scientists’ response to the hiatus. Scientists who were studying the hiatus could have been focusing on providing policy makers with clear information about the reality of global heating and the urgency to address it.

The debates over whether the hiatus was real or not fed public confusion and undermined efforts to convince people to take aggressive action to reduce climate change’s impacts. That’s an important lesson going forward, Lewandowsky says.

“My sense is that the scientific community has moved on,” he says. “By contrast, the political operatives behind organized denial have learned a different lesson, which is that the ‘global warming has stopped’ meme is very effective in generating public complacency, and so they will use it at every opportunity.”

Already, some climate deniers are talking about a new “pause” in global warming because not every one of the past five years has set a new record, he notes. But the big picture is clear: Global temperature have continued to increase in recent years. The seven warmest years on record occurred in 2015, and every decade since 1980 has been warmer than the previous.