[ad_1]

“We want to use our scale and our scope to lead the way,” Amazon founder Jeff Bezos said when announcing The Climate Pledge in 2019.Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP

This story was first published by Reveal and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This is how it worksAmazon isn’t concerned about the climate impact of many of its products. It simply decides that it will follow different rules than its competitors.

Target.com adds to its carbon footprint by counting the emissions associated with all the Pampers purchased from Target. Target.com also adds carbon emissions to customers who order Samsung TVs.

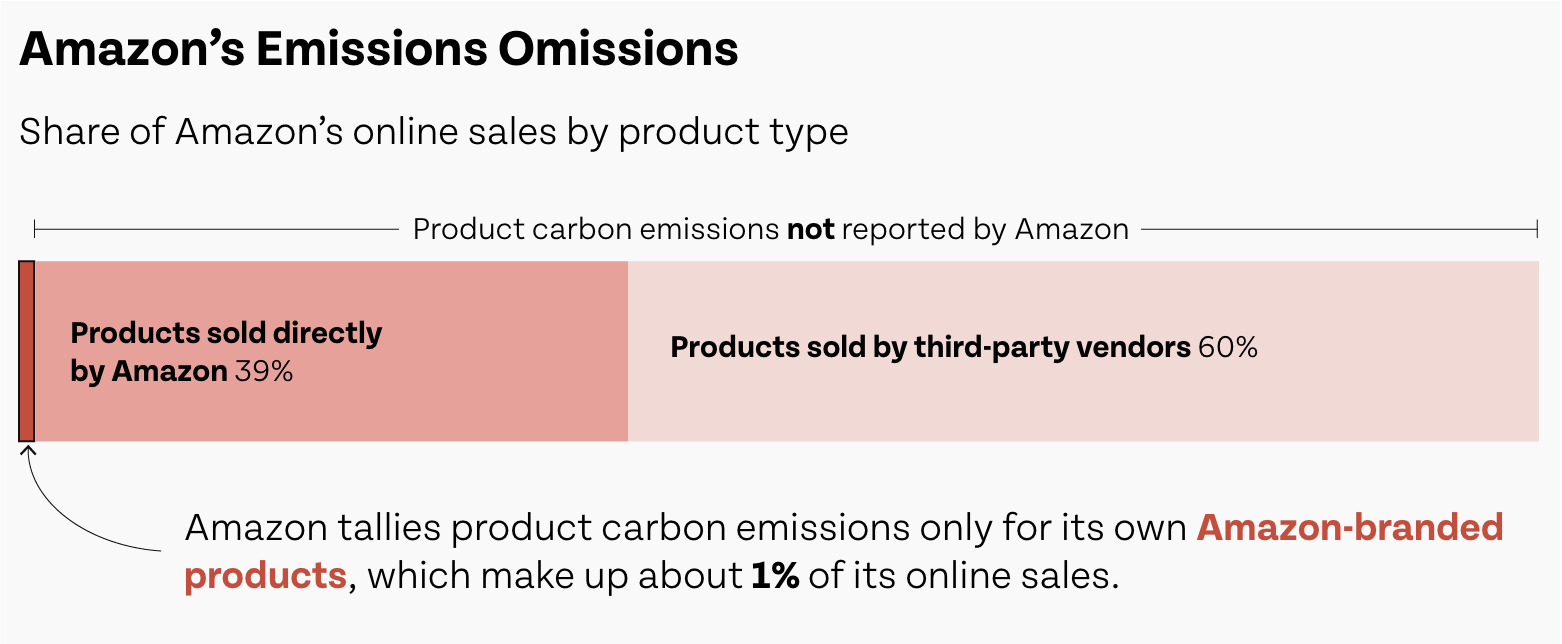

But when shoppers click “Buy Now” on those same products on Amazon, the nation’s largest online retailer doesn’t count those carbon emissions. Amazon is responsible for the full climate impact of only products that have an Amazon brand label. These products account for about 1% of Amazon’s online sales.

The company’s name, which is a river that flows through a forest, was born. Damage by climate change, vastly undercounts its carbon footprint, accepting less responsibility for global warming than even smaller competitors.

Tendencies from activists as well as investors have led to thousands of companies agreeing to disclose their carbon footprints, with the help of a nonprofit organization. CDP (originally known as the Carbon Disclosure Project).

Amazon had been shamed with an F grade for failing to disclose until this past year, when it submitted to CDP’s questionnaire for the first time. Amazon requested that its report not be made public, unlike many other companies being pressured to disclose.

Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting obtained Amazon’s report, and the detailed accounting within illuminates how such a massive company manages to boast such a small carbon footprint.

The report also points out the dangers of relying solely on voluntary commitments and self-disclosures from companies with vested interests in underestimating their accountability. Amazon has positioned itself as a climate change leader, promoting a “Climate Pledge” to zero out emissions by 2040. But by not counting all of its emissions, it isn’t on the hook for cutting them.

Let’s break down the ways that Amazon manages to downplay its carbon footprint.

Usually, the largest is the best chunk of a retailer’s carbon footprint comes from all the products it sells. And that’s where Amazon has the biggest gaps.

Take all the greenhouse gases that are released into the atmosphere by retailers manufacturing the products they sell. For everything with a plug, add in the electricity they eat up when they’re on. Add in the emissions that eventually lead to their destruction.

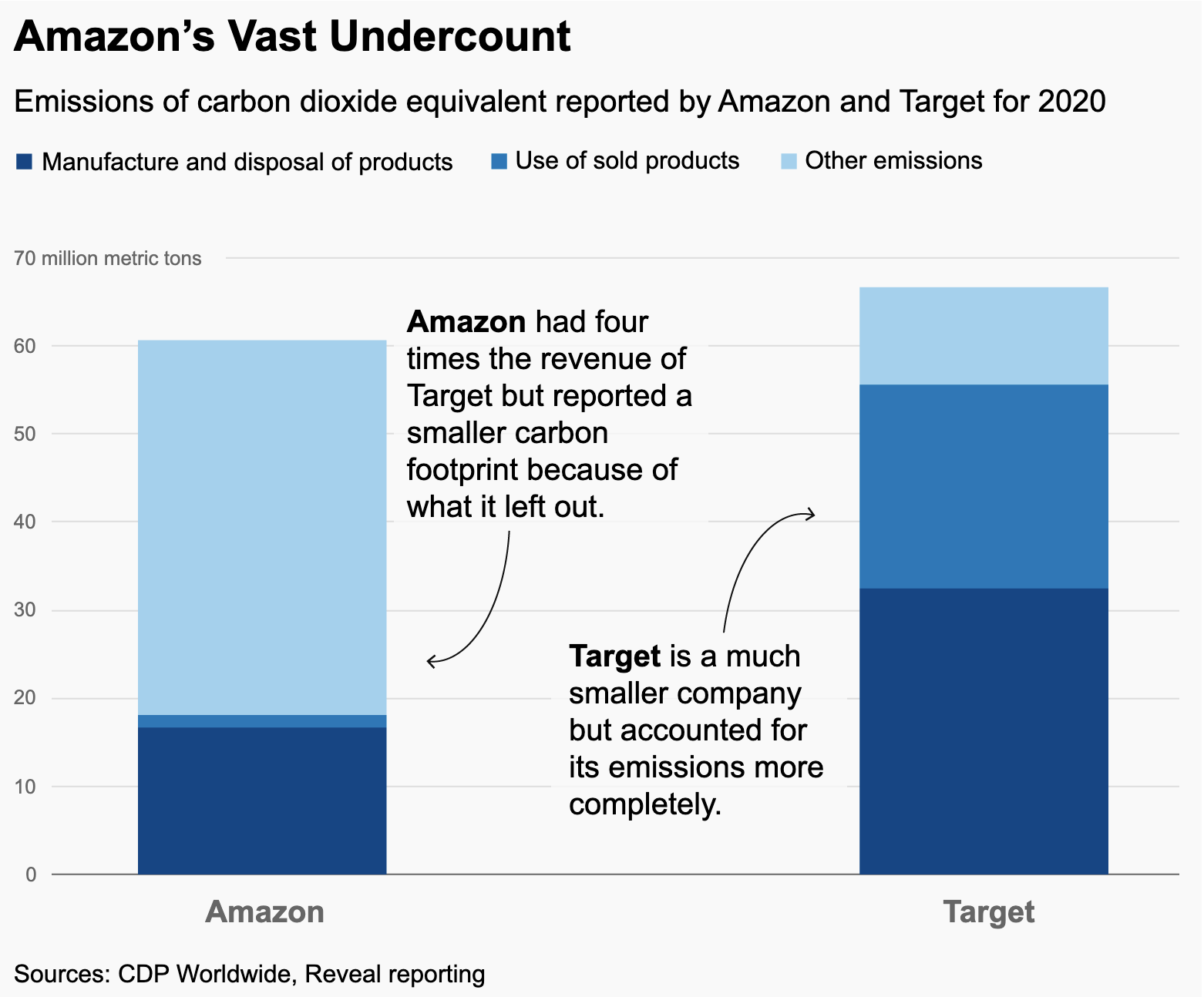

For that lifecycle of consumer products, Target’s report, which it makes public, showed triple the amount of carbon emissions that Amazon’s did. This is 37.5 million metric tonnes more carbon dioxide than Amazon. Similar of just over 8 million cars driven for a year.

And that’s for a year Amazon Racked up well over $100 billion more in sales than Target. How is this possible? Well, Amazon counts only products labeled with its private brands – the Echo Dots, Kindles and AmazonBasics staples, for example. These, according to Amazon, are the totals. 1% of its online sales.

There’s another 39% of sales that Amazon should be counting if it were using the same accounting as its peers. These are the products Amazon buys directly from manufacturers. They’re made by other companies—think Levi’s, Nintendo, Frigidaire—but their product listings say “ships from” and “sold by” Amazon.com. These brands are also available at Walmart and Target. But unlike Target and Walmart, Amazon doesn’t count the emissions that go into making these products—or those that come out of them.

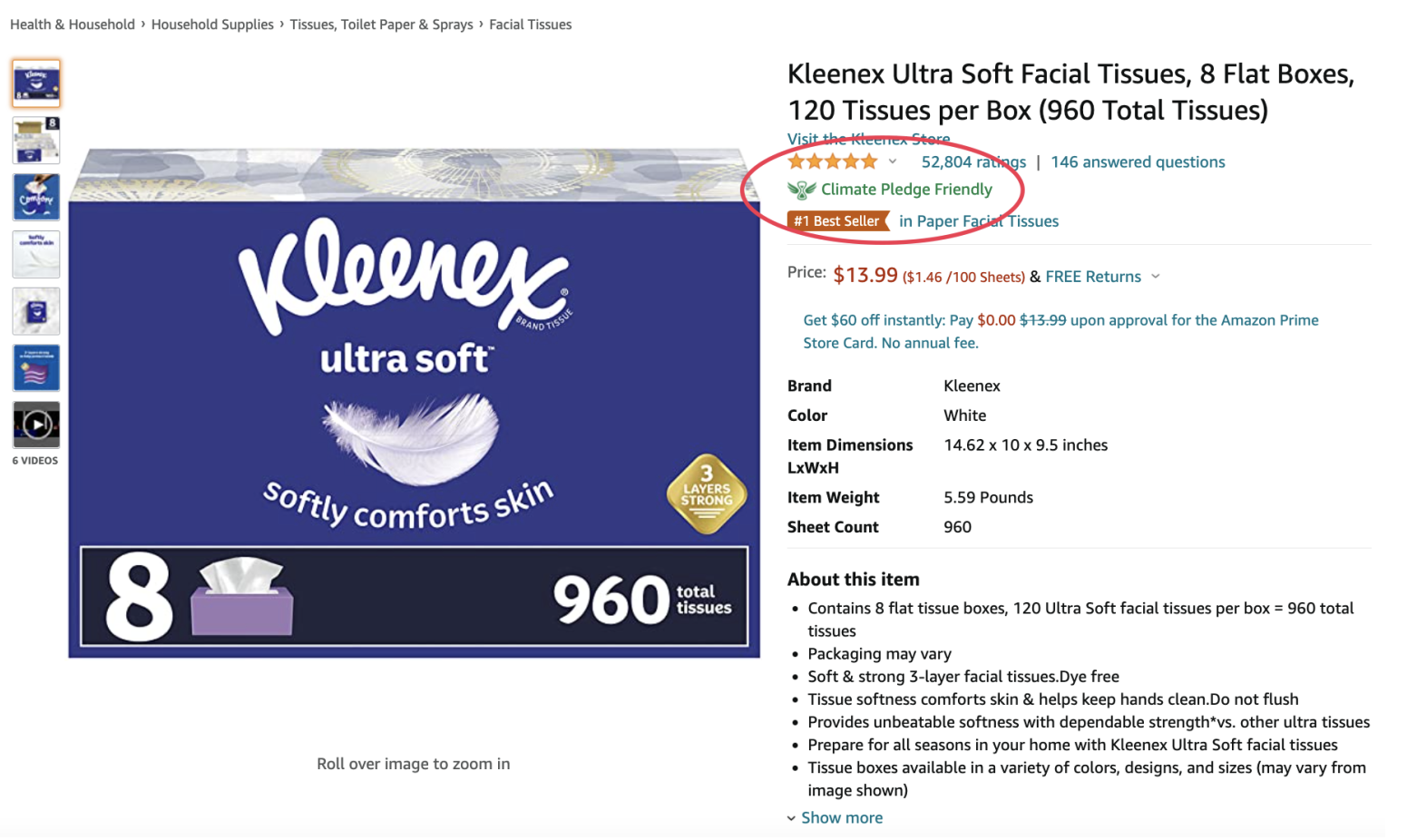

So these products might even be labeled “Climate Pledge Friendly” on Amazon—like a box of Kleenex tissues. But the company doesn’t actually count them toward its Climate Pledge.

Kleenex tissues on Amazon.com are labeled “Climate Pledge Friendly”, but Amazon does not count emissions from non-Amazon brands towards its Climate Pledge.

(The remaining 60% of Amazon’s sales come from third-party vendors who use Amazon as an online marketplace; Amazon doesn’t count those emissions either, but that’s more of a gray area. Amazon spokesperson Luis Davila said third-party sellers “control their own carbon emissions accounting.” Walmart, which also has third-party sellers hawking wares on its website, says it does count those products in its carbon footprint. Target wouldn’t comment on whether it counts third-party sales.)

CDP uses what’s known as the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, which lays out how companies should be measuring emissions. Amazon states it follows the protocol. They have also committed to having their goals validated by Science Based Targets Initiative. This initiative is a partnership between CDP and other organizations that certifies corporate plans for reducing emissions.

But the protocol doesn’t allow companies to count only their own private brand products. Alberto Carrillo Pineda (managing director of Science Based Targets Initiative) stated that retail companies must count all products they sell directly to customers under the protocol.

“Everything you purchased should be included, and everything that you sell should be included,” he said.

(Carrillo Pineda said his organization will have to get a third party to evaluate Amazon because it received $18 million from Amazon’s founder through the Bezos Earth Fund.)

It’s true that these indirect emissions from a company’s supply chain, called Scope 3 emissions, are notoriously difficult to tally, and many companies use guesstimates. But they often represent the majority of a company’s impact on the environment, and counting them forces companies to put pressure on suppliers to clean up their act, too.

There’s another thing Amazon isn’t counting that its peers do. It’s not a large part of Amazon’s footprint—maybe more of a toenail—but it sets the company apart from its rivals.

Amazon had 29% more employees than Target, with triple the number of employees in 2020. There are fewer emissions from their commutes.

That’s because while Target, Walmart, and The Home Depot estimate the gas their workers burn while driving to and from work, Amazon counts emissions only from its own corporate shuttles. Asked about the discrepancy, Amazon’s Davila said: “Employees can use public transportation to get to the office, and if they live nearby, they can walk or bike.”

This is what quadruple means the revenue of Target in 2020 and a sprawling global empire that Target doesn’t have, Amazon actually reported fewer overall emissions than Target that year: the equivalent of about 61 million metric tons of carbon dioxide for Amazon vs. 67 million metric tons for Target.

That can have real-world consequences.

Both Amazon and Target have committed to going “net zero” by 2040, slashing carbon emissions and compensating for what’s left with carbon offsets. So because of what Amazon fails to count, it’s on the hook for eventually canceling out fewer emissions than Target, despite its far bigger impact on global temperatures.

If Amazon were counting its footprint like some of its competition, it would have to get rid of tens of millions more tons of carbon emissions—by radically transforming its business, forcing suppliers to change their own operations, paying for enormous amounts of controversial carbon offsets or maybe even confronting whether The Climate Pledge is compatible with Amazon’s business model after all.

Davila didn’t directly address why the company doesn’t account for the climate impact of most of the products it sells, but reiterated its commitment to cutting emissions, including ordering a fleet of electric delivery vans and buying renewable energy for its electricity needs.

“Amazon is also finding, investing in, and building new solutions to meet the urgency of the climate crisis,” Davila said in a statement.

Amazon is definitely not.The worst carbon lowballer. Costco, for example, doesn’t count lifecycle emissions for any of the things it sells. The company, whose internal slogan is “do the right thing,” is facing blowback, as shareholders Voted to make it own up to all of its emissions and set concrete targets to cut them. Costco’s CDP report is public and will release an action plan by the end the year.

Amazon has been the leader in climate change issues, and others must follow its lead to save the planet. “We want to use our scale and our scope to lead the way,” founder Jeff Bezos said in Announcement The Climate Pledge in 2019, positioning his company as “a role model for this.” The pledge now has more than 200 signatories, and Amazon boasts a $2 billion Climate Pledge Fund and a Seattle sports stadium named the Climate Pledge Arena.

There’s a backstory to the company’s climate marketing. It’s faced intense pressure from a group of inside agitators, Amazon Employees for Climate Justice. Bezos’ announcement came on the eve of an employee walkout protesting the company’s lack of action. Less than a year later, two of the group’s organizers were fired in what the National Labor Relations Board determined was illegal retaliation, leading to a Settlement last year.

Eliza Pan, a spokesperson for the group, is actually a former employee. She speaks for the group as current employees are concerned that Amazon might exact revenge if they speak up.

When Reveal spoke to Pan about the report, she expressed “frustration and anger that Amazon has hidden so much behind PR.”

“It seems like Amazon is misleading employees and the public,” she said, “or even being straight-up deceptive about how well it’s doing against its climate goals.”

Even with the holes in Amazon’s accounting, the company that promises to get to zero by 2040 is going in the wrong direction. Its carbon footprint has increased by just 36% between 2018 and 2020.

Faced with that inconvenient data point, Amazon argues publicly that its “carbon intensity” – the amount of carbon it emits per dollar it makes – improved 16% in 2020.

“This year-over-year carbon intensity comparison reflects our early progress to decarbonize our operations as we also continue to grow as a company,” Amazon’s public Sustainability report states.

But privately, Amazon’s CDP report shows a less impressive figure. CDP asks companies about their carbon intensity. This is based on the direct impact of their operations and energy consumption.

Looked at that way, Amazon’s improvement was 3.9% in 2020 and didn’t stack up well against competitors. Amazon calculated a rate about 39 metric tonnes of carbon emissions for every $1 million of revenue, while Target’s was 29 and Walmart’s 20. Asked about the comparison, Davila said, “We can’t speak for other companies.”

To avoid increasingly catastrophic ravages of climate disaster, scientists warn that the Earth needs to reach “net zero” by midcentury. Humanity is in a crisis. Not on trackMany environmentalists fear that corporate promises to save the planet could lead to dangerous complacency.

A Report from the NewClimate Institute and Carbon Market Watch, two European environmental organizations, gave low marks to most of the large companies it looked at, including Amazon and Walmart. “The change that we require from corporates in the situation that we’re in right now will not come from consumers or shareholders,” said Eduardo Posada, an institute analyst. “We need watchdog initiatives and regulators to hold them to account.”

Amazon is positive, however. “We are relentlessly optimistic about the future,” Kara Hurst, Amazon’s vice president of worldwide sustainability, wrote in last year’s public sustainability report.

But the end of the report includes a boilerplate disclaimer: “No assurance can be given that any plan, initiative, projection, goal, commitment, expectation, or prospect set forth in this report can or will be achieved.”

In other words, don’t hold us to it.

This story was edited and copied by Nikki Frick.