[ad_1]

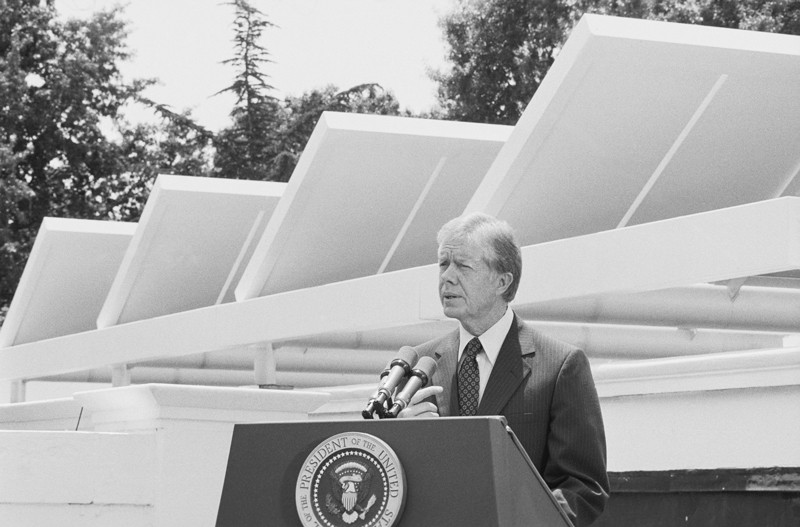

In 1979, Jimmy Carter, the US president, installed solar panels on the White House roof.Credit: Bettmann/Getty

Fire and Flood: A People’s History of Climate Change, from 1979 to the Present Eugene Linden Penguin (2022)

Russia’s violent invasion of Ukraine has sent shock waves through the world’s energy markets, causing oil prices to swing wildly and nations to redraw allegiances over gas supplies. The war could drive the world towards a more decarbonized economy — or further entrench dependence on fossil fuels.

Given the global nature the current events, it seems strange to offer a US-centric perspective about the failure to address climate change. But journalist Eugene Linden’s Flood and FireThere are lessons to be learned from the energy crisis. Despite the book’s US focus slipping into parochialism, it reminds us about the many forces that have prevented society developing effective solutions for the climate crisis. It identifies missed opportunities and highlights strategies for the future, especially in finance and business.

We have covered environmental issues for TimeLinden has been a contributor to the magazine for many years and is an efficient summariser of scientific knowledge. His story begins in 1979 when Jule Charney, a meteorologist, chaired a committee of the US National Academy of Sciences that examined the effects of carbon dioxide on climate. The background is well-known: scientists Eunice Newton Foote, John Tyndall, and John Tyndall noticed that CO was being released into the atmosphere in the 1850s.2Gas heated up quicker than air. Svante Arrhenius, a physical chemist, calculated how much extra CO could be produced in the 1890s.2The planet could be warmed by it. Roger Revelle, an oceanographer was keeping track of the amount of CO that humans had produced by the 1950s.2must be going in the atmosphere, and Charles David Keeling was starting his iconic measurements for CO2 levels above Mauna Loa, Hawaii.

Charney and his colleagues in 1979 were well aware of the fact that CO was being poured into the world.2The atmosphere can have potentially devastating social consequences. Linden provides a useful framework to think about the future. There are four clocks. The first tracks climate change in real time; the clock’s hands advance with every climate-driven storm, drought, flood and other extreme event. Each clock lags behind at different speeds. One represents research. This is an attempt to explain climate change quickly, but it is slowed by publication and investigation. Public awareness is another, which is slower than discovery. The business world is the last and slowest.

Linden reflects on the missed opportunities in the years following 1979. The 1980s saw the United States set back its business clock when President Ronald Reagan cut federal support for the development of renewable energies, particularly solar power. These countries lost technological leadership in these areas to Germany, Japan, and other countries. Exxon and other fossil-fuel companies began to develop highly effective strategies in the United States to delay action on curbing emissions. They also started to doubt the reality of global warming. The clock for public awareness has slowed.

In the 1990s, scientists were doing quite well. Researchers extracted long cores ice from Greenland’s ice sheet to solidify their understanding of how abruptly the climate has altered in the past. Unfortunately, society was not able to keep up. The opportunity to decarbonize quickly was lost by the former Soviet countries after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union. The emerging nations also failed to move beyond dirty energy sources and find cleaner sources of power. China’s coal-fueled rise began.

This era, which lasted until the 2000s, was also a heyday for climate denialism. It was especially prevalent in Australia and the United States where the rhetoric of individual liberty and fighting regulation is deeply rooted. Doubt-merchants fuelled fights over the ‘hockey stick’ graph (showing an abrupt rise in temperatures over time) and whether global warming had ‘stalled’ after the powerful 1997–98 El Niño event, and they stoked the 2009 Climategate scandal over scientists’ internal discussions. The public-awareness clock was further behind.

Linden is a firehose of cynicism directed at international policymakers. He slams the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s reports as being timid, and the United Nations agreements on limiting greenhouse-gas emission as being toothless. His greatest ire, however, is directed at businesses that mortgaged a liveable future for today’s profits. Researchers proposed integrated tools for reducing carbon emissions, such as the 2000s concept of ‘stabilization wedges’: multiple strategies across transport, heating and so on, to collectively reduce emissions. Yet even insurance companies — which, more than any other business, should want to eliminate the risk of climate change sooner rather than later — failed to adequately incorporate such strategies.

In the 2000s and 2010, as extreme weather events became more frequent and global temperatures rose, insurance companies continued their coverage in communities most at risk. Here are the floods, fires, and other disasters mentioned in the title. Many of these events affect the most vulnerable communities. Urban heat, which is exacerbated by climate changes, affects communities most closely along racial or ethnic lines. Not only does sea-level rise affect beach homes in the wealthy, but also poorer areas with less coastal protection. Climate change’s impacts ultimately boil down, as with many other areas in environmental justice, to inequity.

In this, Linden falls well short of other recent histories such as Alice Bell’s Our Biggest Experiment(2021), which explores climate, race and class in a more sophisticated way. Linden’s subtitle of a ‘people’s history’ is odd: there are very few in his narrative who are not scientists, politicians and business leaders. He does not spend enough time exploring how to address climate impacts on low-lying nations that could soon be submerged by the sea-level rising or Indigenous peoples in the fast-warming Arctic.

Linden believes that extreme weather events like prolonged droughts in Australia or hurricanes in North America and the Caribbean are so evident that they could lead to political change in places where there were no previous discussions. But the path to success is not clear. The clocks of public awareness and of business interests, especially, continue to lag behind the reality of what’s transpiring.

The final outlook is even worse. Linden concludes that the global response of COVID-19 shows how ill-equipped the world is to deal with complex, long-lasting problems. Tribalism, misinformation, and autocracy are all on the rise. Even the promise of jobs in an economically decarbonized world is not enough to overcome these forces. Will the collapsing Russian economy drive many nations back to a reliance on fossil fuels, or will the fuel shock caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine accelerate the transition to renewable energies?

This, like many other things in uncertain times, remains to remain to be seen.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interest.