[ad_1]

In 2021, climate change will be a major issue in the world. record heat waves. droughts. wildfires extreme storms. People who have been affected by climate change are often the ones most in need of assistance. done the leastTo cause it.

To reduce climate change and protect those who are most vulnerable, it’s important to understand where emissions come from, who climate change is harming and how both of these patterns intersect with other forms of injustice.

I am interested in the justice dilemmas created by climate change and climate policies and have been an observer at international climate negotiations since 2009. Here are six charts to help you understand the challenges.

Where are the emissions coming from?

One common way to think about a country’s responsibility for climate change is to look at its greenhouse gas emissions per capita, or per person.

China is currently the biggest greenhouse gas emitter country-by-country. However, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, Canada, Australia, and the United State have more than twice the per-capita emissions of China. Each has more than 100 times the per capita emissionsMany countries in Africa.

These differences are important from a justice perspective.

The majority of greenhouse gas emission comes from the United States. come from the burning of fossil fuelsTo power industries, stores and homes, and to produce goods and services including food transportation and infrastructure.

As a country’s emissions get higher, they are less tied to essentials for human well-being. Measures of human well-beingIt is possible to increase your emissions very quickly, but with very little increases in speed. but then level off. This means that high-emitting nations could reduce their emissions while not affecting the well being of their population, while lower-income, less-emitting ones cannot.

Low-income countries have been arguing for yearsIn a context where global emissions must be drastically reduced, this is a necessity. next half-centuryIt would be unfair for them to make cuts in areas in which richer nations have already invested. This would mean that those in richer regions continue to live in high energy consumption and consume a lot of consumer goods, but they will not be able to invest in essential areas.

Responsibility for decades of emission

It is important to remember that climate injustice does not just revolve around current emissions.

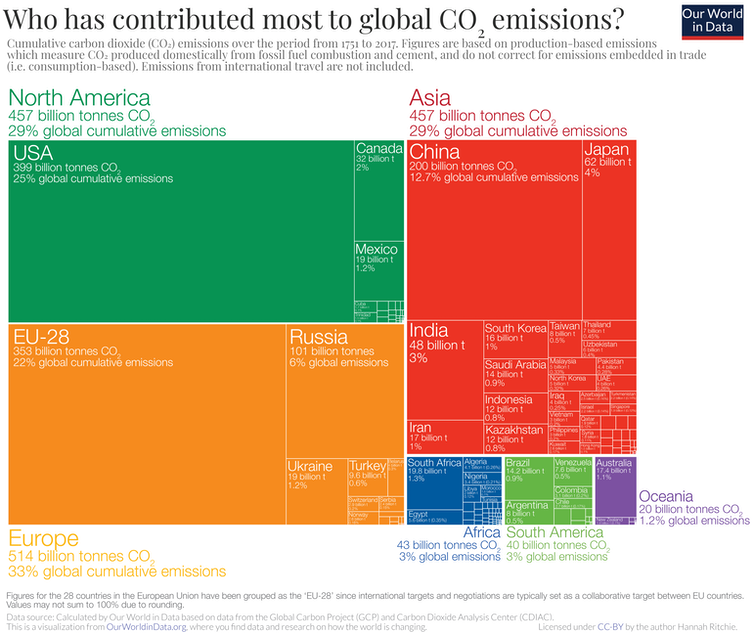

Carbon dioxide remains in our atmosphere. hundreds of yearsThis accumulation drives climate change. Carbon dioxide traps heatThe result is global warming. Some countries and regions have a greater responsibility for cumulative emission than others.

For example, the United States has emitted more than 25% of all greenhouse gases since 1750s. Africa, however, has only emitted 25%. only about 3%.

Hannah Ritchie/Our World in Data. CC BY

Today, people continue to benefit from the wealth and infrastructure that was created with energy linked to these emissions many decades ago.

There are differences in emissions between countries

As well, the benefits of fossil fuels are not evenly distributed across countries.

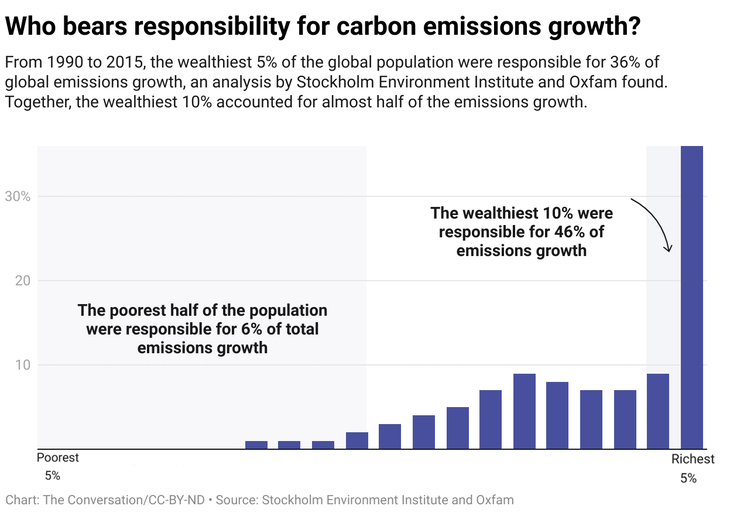

This perspective is the best way to think about climate justice. patterns of wealth. A study by the Stockholm Environment Institute and Oxfam found that 5% of the world’s population was responsible for 36% of the greenhouse gases from 1990-2015. Less than 6% was attributed to the poorest half.

Stockholm Environment Institute and Oxfam. CC BY-ND

These patterns are directly connected to the lack of access to energy by the poorest half of the world’s population and the high consumption of the wealthiest through things like luxury air travel, second homes and personal transportation. They also show how actions by a few high emitters could reduce a region’s climate impact.

In the same way, more than one-third of global carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels or cement in the past half century can be attributed to them. directly traced to 20 companiesprimarily oil and gas producers. This brings attention to the need for policies to hold large corporations responsible for their contribution to climate change.

Who will be affected most by climate change

Understanding the source of emissions is only one part of the climate justice puzzle. Climate change poses greater risks to poor countries and regions.

Some small islands countries, such as TuvaluThe Marshall IslandsAs sea levels rise, so do their chances of survival. Parts of sub-Saharan Africa. the ArcticMountain regions are more vulnerable to climate change than other areas of the globe. Parts of Africa are experiencing rapid climate change as a result of changes in temperature, precipitation, and rainfall. food security concerns.

Many of these countries and communities are not responsible for the greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change. They also have the least resources to protect themselves.

Climate impacts – such as droughts, floods or storms – affect people differently depending on their wealth and access to resourcesThe extent of their participation in decision-making. People who are marginalized, such as colonialism or racial injustice, are less likely than others to be able and willing to take action to protect themselves against climate harms.

Strategies for a just Climate Agreement

All of these justice issues are central to negotiations at the United Nations’ Glasgow climate conference and beyond.

Many discussions will focus on who should reduce emissions and how poor countries’ reductions should be supported. For example, investing in renewable energy can help to reduce future emissions. However, low-income countries will need financial assistance.

Wealthy countries have not been able to keep their promises to provide for their citizens. US$100 billion a yearto assist developing countries adapting to the changing climate. costs of adaptation continue to rise.

Some leaders are asking difficult questions about how to deal with the pressures of leadership. losses that cannot be undone. How can the global community help people who have lost their homes and way of life?

The justice perspective is critical in addressing some of the most pressing issues. These must be addressed both locally and within national borders. Systemic racism cannot and should not be dealt with at an international level. In order to address systemic racism at the national and local levels, laws and other tools that hold corporations responsible will need to be developed within each country.

These discussions will continue well after the Glasgow conference is over.

This story is part of The Conversation’s coverage of COP26, the Glasgow climate conference, by experts from around the world.

The Conversation is here for you to clarify the air and get reliable information amid a flood of climate news stories and stories. Read more of our U.S. global coverage.

Source link