[ad_1]

Salvatore Di Falco, Anna B. Kis, Martina Viarengo 30 April 2022

Climate change is evident in the rise of extreme weather events like floods, droughts, and other natural catastrophes. Many countries with the world’s lowest GDP per capita are located in sub-Saharan Africa, which is also one of the regions in the world most severely affected by the adverse impacts of climate change. The more frequent droughts in rural areas further reduces their economic resilience, which further undermines their development prospects. (Niang et. al. 2014). While migrating to urban areas from rural areas is an adaptive response to these economic shocks Peri and Robert-Nicoud 2021 state that this is a key adaptive response, the existing empirical evidence on the role of environmental factors in influencing migration decisions has been mixed (Neumann et. al. 2015 Cai et al. 2016, Cattaneo & Peri 2015, 2016 Carleton & Hsiang 2016, Mueller. 2020).

In a recent paper (Di Falco et al. 2022), we contribute to this literature by providing new insights on the impact of droughts on agricultural households’ migration decisions in sub-Saharan Africa, and how this varies depending on the intensity and persistence of weather shocks.

Droughts and agricultural production as well as migration responses

The majority of sub-Saharan Africa’s rural population depends on agriculture for its primary source of income. While agricultural practices can adapt to changes in climate over a longer period, the increased frequency and severity if droughts caused by climate change significantly reduces the ability of farmers to adapt quickly (Hertel and Rosch 2011,). If the climate shock is severe or persistent enough that the family’s income from agriculture is not sufficient, rural-urban immigration can be used. On the other hand, migration has substantial costs; in certain cases, if extreme weather shocks are exceptionally harmful, they can end up further constraining households’ choices, including those about migration (Cattaneo and Peri 2016, Peri and Sasahara 2019).

Both arguments are frequently mentioned in public debates, with climate change at the center of policy and research. Cattaneo and colleagues found mixed empirical evidence to support a direct link between climate change and migration. 2019). Many macro-level studies based on lower-frequency census data show that climate shocks have a significant impact on migration, potentially accelerating urbanisation, especially for sub-Saharan African agricultural societies (Marchiori, et al. 2012, Barrios et al. 2006). However, within-country analyses using household data demonstrate that this impact depends on household and individual characteristics (Naudé 2010, Beine and Parsons 2015, Gray and Wise 2016).

We combine the benefits of both the micro and macro approaches to create a large rural household panel with around 140,000 individual-wave observations. This unique dataset has the advantage to have higher external validity because it includes multiple countries, while maintaining statistical robustness high due to a large sample.

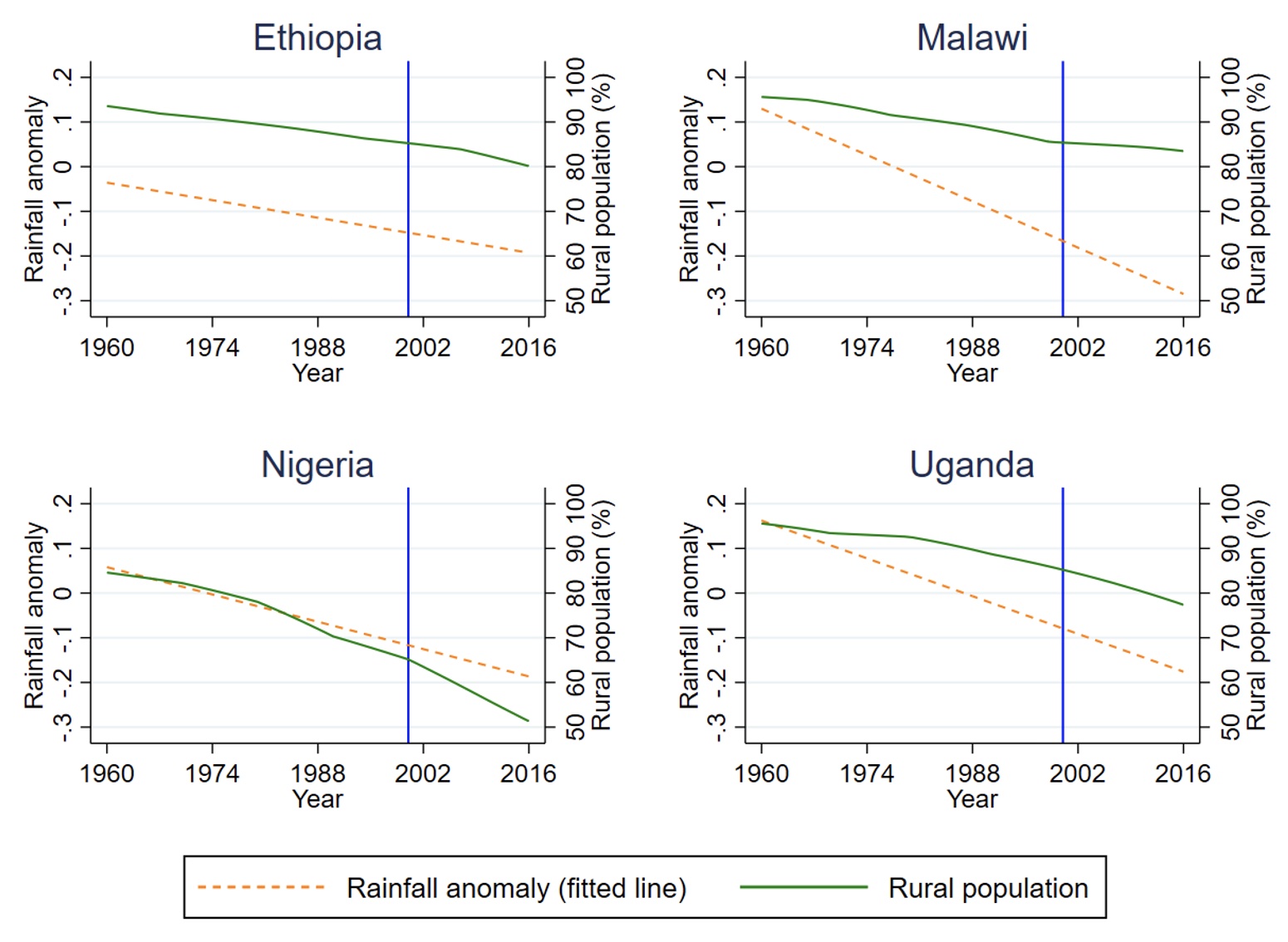

Figure 1 shows that there is evidence suggesting that there is a relationship between precipitation shortages and increased urbanization in the last decade in four of our sample countries: Uganda, Malawi, Nigeria and Uganda. As you can see in the negative trend in standardised rainfall anomalies,1 a measure of drought adapted to local climate conditions, the quantity of growing-season rainfall has been decreasing since the 1960s, reflecting an increasing frequency of droughts. On the other hand we see a steady decline of rural households in our total population. This indicates an urbanization trend which is particularly advanced in Nigeria, the only middle-income country in our sample. However, it was evident starting in the 1980s in Uganda and a bit later in Ethiopia and Malawi. The decrease in rainfall and the increase in rural population are somewhat similar trends, especially after 2000 (marked by a horizontal line). While there are differences in the pace at which urbanization is taking place across countries, the similarities of the trends suggest a possible relationship between extreme climate events and rural-urban migration.

Figure 1Frequency and intensity of droughts and urbanisation

Source: Authors’ calculations based on World Bank World Development Indicators (share of urban population) and CRU TS climate data.

NoteBased on the World Bank indicators, a percentage of rural population is included in the calculation of the country’s total population. Rainfall anomaly is a standardised measure that measures extreme precipitation events. It’s calculated as follows: Long-term average rainfall is subtracted from the annual growing-season rainfall and divided by the long term standard deviation of rainfall. The year 2000 is marked by a vertical line.

Exposure to droughts repeatedly and migration decisions

We use a fixed effects regression method to confirm the intuition in Figure 1. First, we analyze whether individuals are more likely migrate if there has been a drought in the years preceding the migration decision. We compare the effects of severe droughts and droughts that are large enough to significantly disrupt agricultural production.2 (relatively frequent, moderately harmful to crops), and extreme droughts (rare, extremely harmful to crops).

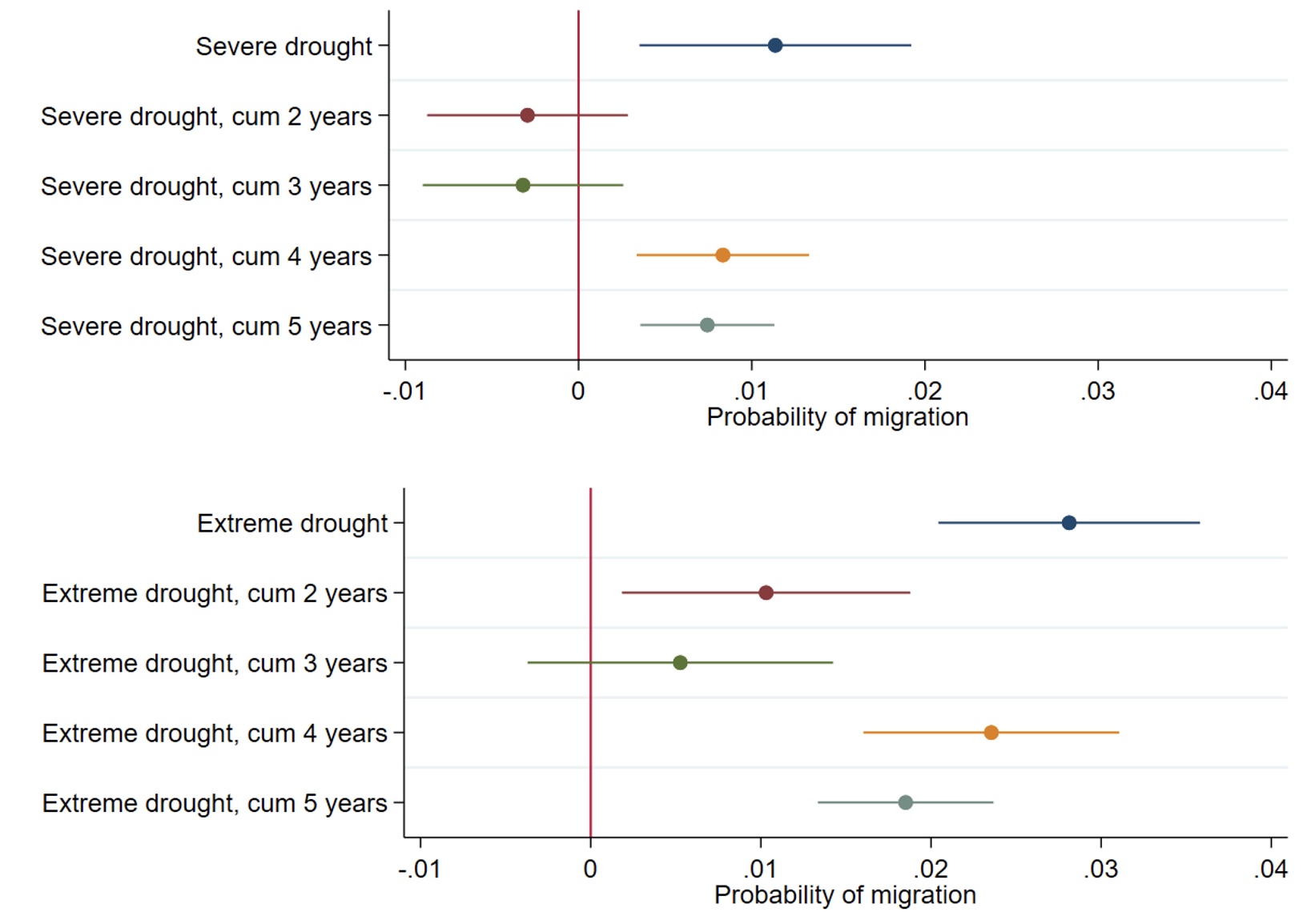

In Figure 2, we present the marginal effects of various climatic shocks – that is to say, we show the increase in the probability of migration induced by different types of droughts. As expected, rural migration accelerates after severe and extreme droughts. Although droughts have a moderate effect, severe droughts can cause migration to increase by 2.8% (compared to 1.1% for severe droughts). This supports the idea that droughts’ primary impact is through the agricultural channel. Therefore, severe droughts (1.1%) have a twice greater migration-inducing effect (2.8%) than severe droughts (1.1%).

Figure 2Marginal effect of climate shocks on migration probability by persistence and severity

Source: Authors’ calculations based on World Bank LSMS and CRU TS climate data.

Notes: The coefficients are based on a fixed effect regression with the following controls. Severe droughts can be defined as a standardised rainfall anomaly where the wettest three quarters were at least 0.5, but less than 1.5 standard deviations lower than the long-term mean. Extreme droughts are defined by standardised rainfall anomalies in which the wettest quarter was more than 1.5 standard deviations lower than the long-term average. The sum of the past one to five year’s severe and extreme droughts is called the “severe” and “extreme droughts. Additional information is available for the other.

We also estimate the effect of droughts that occurred several years before the decision was made to migrate. We argue that if rainfall shortages gradually erode households’ adaptation capabilities, which is the case when they repeatedly destroy crops, then the droughts’ impact is likely to persist for more than one year, and migration from rural to urban areas can remain high for several years after the droughts occurred. This hypothesis is tested by comparing the impact of a drought on a household in the last year (first and fifth lines of Figure 2) with the impact on a drought on the household at any time in the past two to five decades (second to fifth lines of Figure 2).

One, extreme and severe droughts can have a lasting impact on migration, increasing it for at least five more years. This effect does not diminish or disappear over time. The average impact of experiencing additional severe or severe droughts in the past five year (0.7% and 1.8% respectively) is comparable to the impact of suffering from severe or severe droughts in the previous years (1.1% and 2.8% respectively). All severe and extreme droughts that households experienced in the past five years have an impact on the contemporaneous probability of migration, resulting in a much higher number of migrants than we would expect based on the effect of last year’s droughts alone. This means that a single drought may have a moderate effect on migration, but a series of severe shocks has a greater impact. It can range from 0.7% for one severe drought to 9% for five severe droughts.

To get an idea of the magnitude of the impact, imagine the following scenario: The combined population of the five countries included in this sample was subject to one severe and three extremely dry years for five consecutive years. The cumulative effect over multiple years would be five times that of the annual impact, resulting in a total of 1.1 million additional rural migrants in the five countries.

This finding is in addition to the evidence from studies on natural catastrophes in Mexico and Southeast Asia (Bohra-Mishra, et al. 2014, Sedova, Kalkuhl 2020 and Saldana-Zorrilla 2009 Our study shows that it is important to consider the cumulative effects of past weather shocks when investigating migration decisions.

Conclusion

We present a new dataset, which is based in five sub-Saharan African African countries. It shows that focusing only upon the short-term effect of weather events may result in underestimating the impact of climate changes on rural-urban migration. Our results highlight the importance of studying the cumulative effect of climate change and other shocks over the course of time to improve our understanding of the factors that determine migratory flows, their impact upon individuals and on the sending- and receiving regions. Global climate change policies must address the impact of climate change on low-income countries and vulnerable farmers in a climate where many climatic models predict an increase in the frequency and severity of extreme events in Africa.

Refer to

Barrios, S, L Bertinelli and E Strobl (2006), “Climatic Change and Rural-Urban Migration: The Case of Sub-Saharan Africa”, Journal of Urban Economics 60: 357–371.

Bohra-Mishra, P, M Oppenheimer and S M Hsiang (2014), “Nonlinear permanent migration response to climatic variations but minimal response to disasters”, PNAS 111(27).

Cai R, S Feng, M Oppenheimer and M Pytlikova (2016),” Climate variability and international migration: The importance of the agricultural linkage”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 79: 135–151.

Carleton, T A and S M Hsiang (2016), “Social and economic impacts of climate”, Science 353(6304).

Cattaneo, C and G Peri (2015), “Migration’s response to increasing temperatures”, VoxEU.org, 14 November.

Cattaneo, C and G Peri (2016), “The migration response to increasing temperatures”, Journal of Development Economics 122: 127–146.

Cattaneo, C, M Beine, C J Fröhlich, D Kniveton, I Martinez-Zarzoso, M Mastrorillo and B Schraven (2019), “Human migration in the era of climate change”, Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 13(2): 189–206.

Di Falco, S, A B Kis and M Viarengo (2022), “Climate Anomalies, Natural Disasters and Migratory Flows: New Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 15084 and IHEID Center for International Environmental Studies Work Paper No. 73/2022.

Gray, C and E Wise (2016), “Country-specific effects of climate variability on human migration”, Climatic Change 135: 555–568.

Henderson, J V, A Storeygard and U Deichmann (2016), “Has climate change driven urbanization in Africa?”, Working Paper.

Hertel, T and S Rosch (2011), “Climate change and agriculture: Implications for the world’s poor” VoxEU.org, 17 March.

Mueller, V, G Sheriff, X Dou and C Gray (2020), “Temporary migration and climate variation in eastern Africa”, World Development (2020), 126: 104704.

Naudé, W (2010), “The Determinants of Migration from Sub-Saharan African Countries”, Journal of African Economies 19(3): 330¬–356.

Neumann, K, D Sietz, H Hilderink, P Janssen, M Kok and H van Dijk (2015), “Environmental drivers of human migration in drylands – a spatial picture”, Applied Geography 56: 116–26.

Niang, I, O C Ruppel, M A Abdrabo, A Essel, C Lennard, J Padgham and P Urquhart (2014), “Africa”, in Climate Change 2014: Adaptation, Impacts, and Vulnerability Part B: Regional Aspects Cambridge University Press, 1199–1265.

Peri, G and A Sasahara (2019), “The effects of global warming on rural–urban migrations”, VoxEU.org, 15 July.

Peri, G and F Robert-Nicoud (2021), “The economic geography of climate change”, VoxEU.org, 11 October.

Sedova, B and M Kalkuhl (2020), “Who are the climate migrants and where do they go? Evidence from rural India”, World Development 129, 104848.

Saldana-Zorrilla, S and K Sandberg (2009), “Spatial econometric model of natural disaster impacts on human migration in vulnerable regions of Mexico”, Natural Disasters 33:591–607.

Endnotes

1 Rainfall anomaly refers to a standardised measure for extreme precipitation events. It is calculated as follows: The long-term growth-season mean rainfall is subtracted in a given year and divided by the long-term standard deviation.

2 Severe droughts are defined as standardised rainfall anomalies where the wettest quarter rainfall was at least 0.5, but less than 1.5 standard deviations below the long-term mean. Extreme droughts can be defined as anomalies of standardised rainfall where the wettest quarter was more than 1.5 standard deviations lower than the long-term mean.