[ad_1]

Tiny temperature drops have caused chaos around the world throughout the century, even in Taiwan

-

By Michael Turton / Contributing reporter

In the 17th century, something like a third of the world’s population died.

Geoffrey Parker, in his monumental book on that terrible century, Global Crisis: War, Climate Change & Catastrophe in the 17th Century, itemizes the climate disasters that overwhelmed Europe, Asia, India and the Americas. Japan had its coldest spring ever in 1616. It also snowed in Fujian 1618. In the 1620-30s, successive droughts and floods in India, Europe, and other countries ravaged many countries’ harvests.

One of the “years without a summer,” 1628, followed 1627, the wettest summer in Europe in 500 years. Global tree ring data reveals that the 1640s saw terrible floods, droughts and cold all over the globe. In Scandinavia, 1641 was recorded as the coldest year.

Photo courtesy Wikimedia.

The cruelty of the first century continued in the second half. All over the northern hemisphere, 1675 was remembered as another “year without a summer.” In 1683-84, the Thames froze over for weeks, and bull baiting exhibitions were held on the ice. Between 1650-1680, the Russian population fell as the harvests failed repeatedly in the face the coldest autumn-to spring stretches in 500 years.

Famine and the plague ruled from China to Catalonia. Cities and towns saw their populations plummet, tax rolls vanished, revolts, wars and revolutions broke out, and land and sea became the playground of bandits and pirates. The poor were also subject to cannibalism as well as infanticide and suicide. All across Europe, town registers tell the same story about young males who were killed in war and their populations being decimated by plundering and plague.

Parker says that our science, the lineal descendent to Enlightenment inquiry was created in part by the successions of crises. He does not blame witches (900 people were killed in south Germany after one bout in bitter weather in 1626), or comets.

Photo courtesy Wikimedia.

Numerous lines of evidence show that after 1645 the sun’s output fell, a period known as the Maunder Minimum. The period between 1638 and 1644 saw 12 enormous volcanic explosions around the Pacific, filling the earth’s atmosphere with dust and cooling the planet. The rest of the damage was done by plagues and wars.

The taxes came next.

DEBT-DRIVEN UNTREST

Photo courtesy Wikimedia.

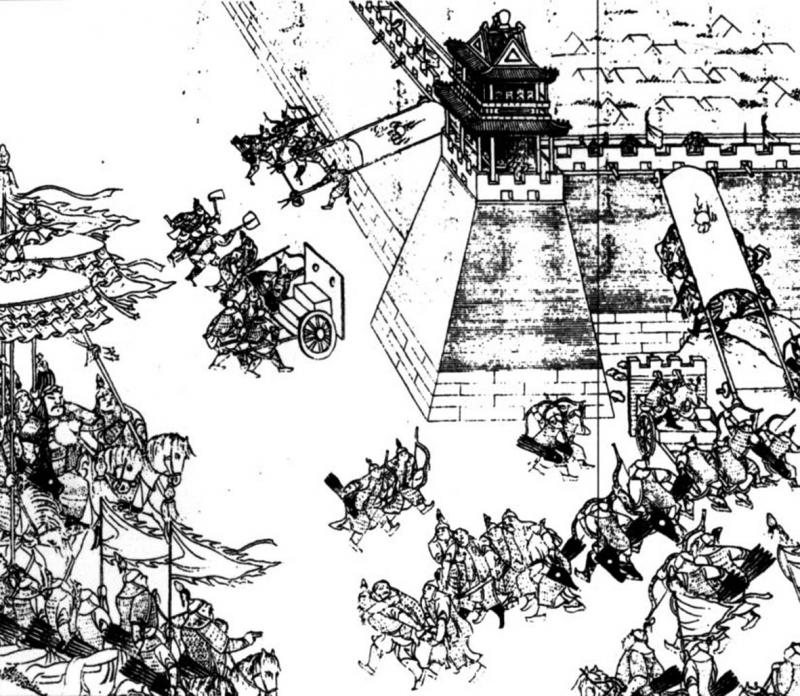

Koo Hui-wen (古慧雯) in “Weather, Harvests, and Taxes: A Chinese Revolt in Colonial Taiwan” described how a global phenomenon appearing locally generated the famous revolt of Kuo Huai-yi (郭懷一). Around the globe, the succession of failed harvests caused those in debt to rise up against taxes (especially new ones that would fund the constant warfare) as well as debts that couldn’t be paid, causing the toll of death, instability, and even death.

Koo claims that a Taiwanese Han farmer Kuo received loans from the Dutch in the form pepper to finance sugar plantation. However, 1651 was too dry in Taiwan and the sugar harvest was poor. These loans could not be repaid. Other farmers were rallied by longstanding issues with tax collection, debt, and in 1652, the Han staged their greatest revolt since the Dutch era.

The climate crisis drove unrest in other ways. A series of poor harvests with the attendant food trouble in the 1630s in northeast Asia led Manchu leaders to conclude that they had to “invade China or perish,” as Parker put it. Tree ring data shows that for 1643-44 were the coldest years in East Asia between 800 and 1800, with temperatures falling over 2°C on average throughout the midcentury period. North China was hit by its worst drought for 500 years in 1640.

In part, the climate crisis and the Manchu invasion of 1644 accelerated the Ming dissolution. This chaos and destruction was felt in Taiwan as a loss for markets. In 1650, the Taiwan Strait saw the collapse of the price of venison. Koo says that although the Dutch had monopolized the trade in deer products and the colonial authorities decreased the payments, many Han holders of monopolies found themselves in jail for unpaid loans. Revolt was an attractive alternative.

The already unpayable tax burden was further increased by a poll tax that was introduced in 1639. Dutch soldiers began to prey upon civilians by extorting money or in kind, beating them, and entering homes to rob them. This caused bitter resentment.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) crushed Kuo’s revolt. They fielded veterans against Han farmers: around 60% of their soldiers, sailors and marines were actually German. Many of these were the result of a floating population displaced by the bloody Thirty Years War between 1618 and 1648.

TWO DEGREES

In Taiwan we focus on the Dutch Era as part of Taiwan history — part of the way we often fail to background Taiwan history against the global events that drive it — but for the Spanish and Dutch, Taiwan was part of an overall strategy for monopolizing the trade along the China coast and the whole corridor from the Moluccas (now the Maluku Islands in Indonesia) to Japan as Jose Eugenio Borao has described in “‘Intelligence-gathering’ episodes in the ‘Manila-Macao-Taiwan Triangle’ during the Dutch Wars.”

Bartolome Martinez from Dominica, an emissary to the Dominican, went to Macau to purchase ammunition. He also warned the Chinese not to send any ships to Manila. In 1619, he suggested that the Spanish set up a fort in Pacan (likely Beigang now in Tainan) in order to protect the trade with China and help with the Dutch blockades of Manila.

This would have made Taiwan a part of Manila and its market, and perhaps the Spanish would have colonized Taiwan. Today, Taiwan might be considered one more island in the Spanish Philippines. Instead, the Chinese proposed that the Dutch relocate to Taiwan in 1623. The rest is history.

The terrible century continued in Europe. The Spanish and Dutch went to war again in 1640. This time, the Dutch evicted Malacca’s Portuguese inhabitants and took Keelung, with guns taken from Malacca, the next year.

In 1641, Portugal became independent, Phelim O’Neill and Rory O’Moore, deeply in debt, led the Irish in revolt after a bad harvest, the Nile fell to the lowest level ever recorded, and 12 years of drought began in the Canadian Rockies. Spain was itself plagued by revolts, skyrocketing food costs, social disorder, and endless war for a decade.

All these agonies were caused by a tiny drop in solar radiation combined with volcanism that varied temperatures just 1 to 2°C for the century.

Isn’t there a famous goal that calls for limiting temperature change to 2°C?

Notes From Central Taiwan is a column written and edited by Michael Turton (long-term resident), who shares incisive commentary from his three decades of experience living in and writing about Central Taiwan. These views are his.

Moderators will moderate comments. Please keep comments relevant to the article. Comments containing abusive or obscene language, personal attack of any kind, or promotion will result in the user being banned. Final decision will be made by the Taipei Times.

[ad_2]