[ad_1]

After years of punishing drought in some areas, many farmers in Australia’s east were hoping the newly declared La Niña eventThey would receive good rains.

Many are celebrating the most wet November in Australia’s history. However, heavy and prolonged rains are causing new problems for farmers.

Last year’s La Niña delivered good rainfall in some areas – while leaving others drier than they would have been under an El Niño, with many areas in southern Queensland missing out. In La Niña years, the cattle farming town of Roma receives an average of 247mm from November to the end of January. They received only half of that last year.

This year’s La Niña has already delivered rain to many areas left dry last year. Roma, for instance, received more than 200mm in November 2021. These large rainfall events and seasons are necessary after prolonged droughts to replenish the soil’s moisture.

However, it will be less welcomed in newly waterlogged areas along Queensland’s NSW border and Northern Rivers region as it could lead to more flooding.

Continue reading:

Climate change is likely driving a drier southern Australia – so why are we having such a wet year?

What does La Nina really mean for farmers?

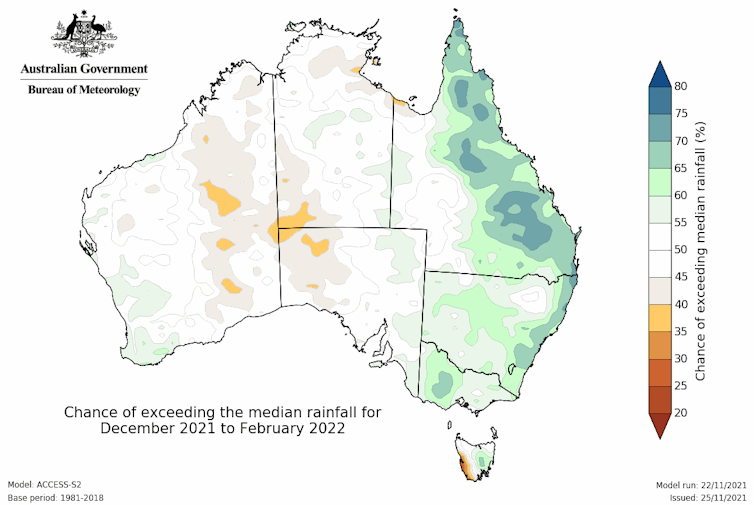

Seasonal forecastsFrom now until March, a greater than 60% chance for rainfall in eastern Australia will be above the median.

Many farmers in eastern Australia have been experiencing below-median rainfall levels for three or more consecutive years. This will be good news for them.

Bureau of Meteorology, CC BY

Farmers usually welcome La Niña with open arms, given plentiful rainfall can boost production and profits.

However, a boon to one industry may be a burden to another. Heavy or prolonged rainfall can damage delicate crops and fruit, delay harvests, or make them more difficult. Flooding can flood entire fields and cause destruction to roads and other infrastructure.

Lukas Coch/AAP

For the sugar industry, increased rainfall associated with La Niña can mean sugarcane has to be harvested at lower sugar content levels, or be delayed in harvesting. Heavy rain can cause cane to be ruined, making harvesting more difficult and reducing yield. This can all lead to lower profitability.

The bumper crop of 2021 is a big win for the grains industry already been downgradedFlooding in New South Wales has led to losses in the billions in areas such as New South Wales.

By contrast, the beef industry in Queensland relies on grass, so a La Niña summer with above average rain can increase pasture growth and regeneration as well as cattle weight gain and market prices.

This double-edged sword – too much rain or not enough – is nothing new to Australian farmers.

Understanding how La Niña and other ENSO (El Niño-Southern Oscillation) events impact different regions and industries is critical to take advantage of good years, minimise losses in poor years, and make sound decisions based on the best possible information.

What does that look? In La Niña years, cattle farmers may decide to move their cattle out of flood prone regions or rest a paddock to allow it to regenerate with the extra rain, which will provide more grass in the following season.

For grain farmers, La Niña means keeping a close eye on both three-month seasonal climate forecasts and the daily weather forecasts to decide if it’s worth the risk to plant a big crop and if they are likely to be able to harvest it before any big rainfall events occur.

Continue reading:

Yes, Australia is a land of flooding rains. But climate change could be making it worse

Shutterstock

Can we predict La Niña rainfall?

La Niña events usually bring average to above average rain to much of Australia’s east. Unfortunately, no two La Niñas occur in the same way.

Because of this variability, it is important for farmers to understand how La Niña events impact their area so that they can plan for likely conditions.

Australia’s east coast climate is heavily influenced by the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a naturally occurring phenomenon centred in the tropical Pacific that consists of three separate phases: La Niña, El Niño, and a neutral or inactive phase.

La Niña years occur around 25% of the time, with El Niño years also at 25%, and neutral years making up 50%. ENSO is not completely predictable and can change between these phases irregularly. While it is unusual to have back-to-back La Niñas it is not unprecedented.

During these La Niña events, surface water in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific cools and the ocean to the north of Australia tends to warm.

Changes in the ocean cause changes in Pacific’s atmosphere. This Pacific phenomenon ripples outwards like a rock being thrown into a pond. It causes atmospheric changes in places such as Australia and Chile.

In Australia, La Niña tends to bring more rain and lower temperatures across much of the country, while we see increases in heavy rain, flooding, and severe tropical Cyclones making landfall.

What is the future? While most La Niña events are projected to produce less rainfall in many regions, projections suggest the wettest La Niña years will tend to be just as wet or wetter that they were in the past.

Australia’s farmers will continue to face the challenges of floods and droughts brought by La Niña and El Niño, but as farmers learn more about these events and how they impact their area and industry, they can become more resilient.