[ad_1]

Lifting hundreds of millions of people out of “extreme poverty” – where they live on less than US$1.90 per day – would drive a global increase in emissions of less than 1%, according to new research.

The study was published in Nature SustainabilityThe report, which highlights the global inequalities in emissions between people from rich and poor countries, is called “Global Inequality in Emissions.” It finds that the average carbon footprint for a person living in sub-Saharan Africa contains 0.6 tonnes of carbon dioxide (tCO2). Nevertheless, the average American citizen produces 14.5tCO2 annually.

The average carbon footprint of the top 1% of emitters was 75 times greater than that of the bottom 50%, according to the authors.

“The inequality is just insane,” the lead author of the study tells Carbon Brief. “If we want to reduce our carbon emissions, we really need to do something about the consumption patterns of the super-rich.”

A scientist not involved in the research says that “we often hear that actions taken in Europe or the US are meaningless when compared to the industrial emissions of China, or the effects of rapid population growth in Africa. This paper exposes these claims as wilfully ignorant, at best”.

Emissions inequality

Humans release Tens of millions of tonnes CO2Each year, these emissions are released into the atmosphere. However, their distribution is not known. Unequal – as they are disproportionately produced by people in wealthier countries who typically live more carbon-intensive lifestyles.

The new study uses what it calls “outstandingly detailed” global expenditure data from the World Bank Consumption DatasetFrom 2014, to assess the carbon footprints for people in different countries and with different consumption levels.

Dr Klaus HubacekProfessor of Science, Technology and Society at the University of GroningenHe is also an author of the study. Carbon Brief hears from him about the consumption figures.

“Driving the model with the consumption patterns calculates the carbon emissions not only directly through expenditure for heating and cooling, but the embodied carbon emissions in the products they buy. So it’s taking account of the entire global supply chains to calculate those carbon emissions.”

Dr Yuli Shan – a faculty research fellow in climate change economics at the University of Groningen – is also an author on the study. He explained that the use of consumption data allows carbon emissions to be linked to countries that use goods or services, and not the countries that produce them. This is important, because “poor countries emit large quantities of CO2 due to the behaviour of people in developed countries”, he adds.

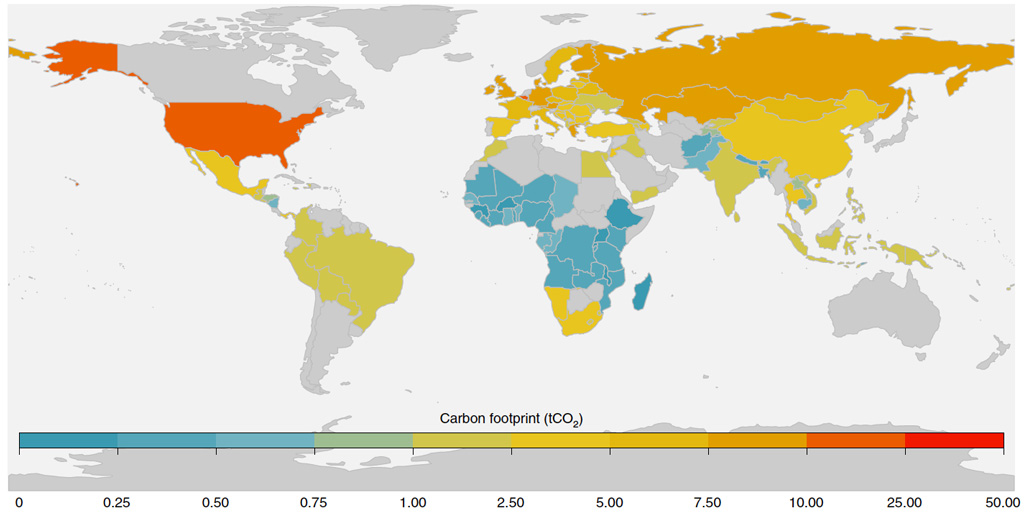

The map below shows the average carbon footprint of residents in the 116 countries covered by the study. The shading indicates the carbon footprint size, from low (blue), to high (red). The colour bar has an exponential scale.

According to the authors, LuxembourgAt 30tCO2 per capita, the US has the highest carbon footprint. The US is second with 14.5tCO2. It is worth noting, however, that there are many countries with high per-capita emissionsThe study does not include countries such as Australia, Canada and Japan.

However, Madagascar, Malawi and Burkina Faso, Uganda as well as Ethiopia, Uganda, Ethiopia, and Rwanda have an average carbon footprint of less than 0.02tCO2.

Dr Shoibal ChakravartyAs a fellow in climate change mitigation and program development in the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, who was also not involved with the research. He tells Carbon Brief that the study “significantly improves on previous attempts” to measure per-capita emissions, and is “more rigorous that past efforts”.

The rich and the ‘super-rich’

The authors also divided the population by how much they spend on average within each country. Benedikt Bruckner – the lead author on the study, also from the University of Groningen – tells Carbon Brief that while previous studies typically used four or five groups, this study uses more than 200.

The high number of “expenditure bins” allows for “more precise, more detailed [and] more accurate” analysis, Hubacek says.

When including bins, the spread of carbon footprints ranges from less than 0.01 tCO2 for more than a million people in sub-Saharan countries to hundreds of tonnes of CO2 for about 500,000 individuals at the top of the “global expenditure spectrum”, the authors find.

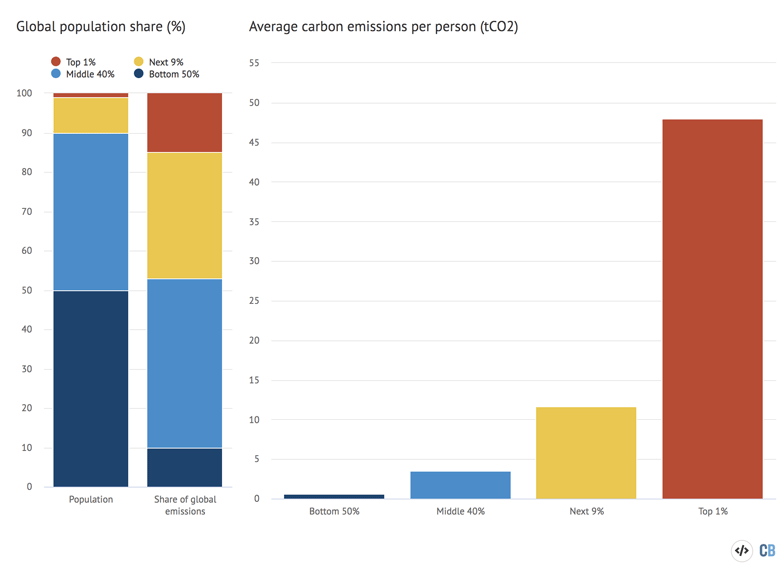

The authors then divided the global population into top 1%, next 10%, next 40%, and bottom 50% of emitters. The authors show their share of global emissions (left), and average carbon footprint (right). These are shown below in red, yellow and light blue, and dark blue.

The global share of carbon emitted (left) and the average carbon footprints of the top 1% to 9% of emitters (right). Chart by Carbon Brief, using Highcharts. Credit: Bruckner et al (2022).

The average carbon footprint of the top 1% emitters is more than 75 times greater than that of the bottom 50%, according to the study.

This gap is “astonishing”, Dr Wiliam lamb – a researcher at the Mercator Research Institute who was not involved in the study – tells Carbon Brief. He adds that responsibility for global emissions lies with the “super-rich”:

“In the public conversation on climate change, we often hear that actions taken in Europe or the US are meaningless when compared to the industrial emissions of China, or the effects of rapid population growth in Africa. This paper exposes these claims to be wilfully ignorant at best. By far the worst polluters are the super-rich, most of whom live in high income countries.”

Lamb notes that the expenditure of the “super-rich” may be even higher than suggested by this analysis, because “their earnings may be derived from investments, while their expenditures can be shrouded in secrecy.”

Get our free Daily BriefingOur digest of the past 24 hour’s climate and energy media coverage. Weekly BriefingFor a complete round-up of our content for the past seven days, click here Enter your email below.

Dr Bruckner also highlighted this underestimation. Noting that the highest carbon footprints in the study are up to hundreds and thousands of tonnes of carbon dioxide per year, past studiesCarbon footprints for the super-rich can exceed 1,000 tonnes per annum, according to estimates. “The inequality is just insane,” he tells Carbon Brief. He added:

“If we want to reduce our carbon emissions, we really need to do something about the consumption patterns of the super-rich.”

Eradicating poverty

2015 saw the United Nations establish a number of guidelines. Sustainable Development Goals – the first of which is to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere”. The goal focuses on eradicating “extreme poverty” – defined as living on less than US$1.90 per day – as well as halving poverty as defined by national poverty lines.

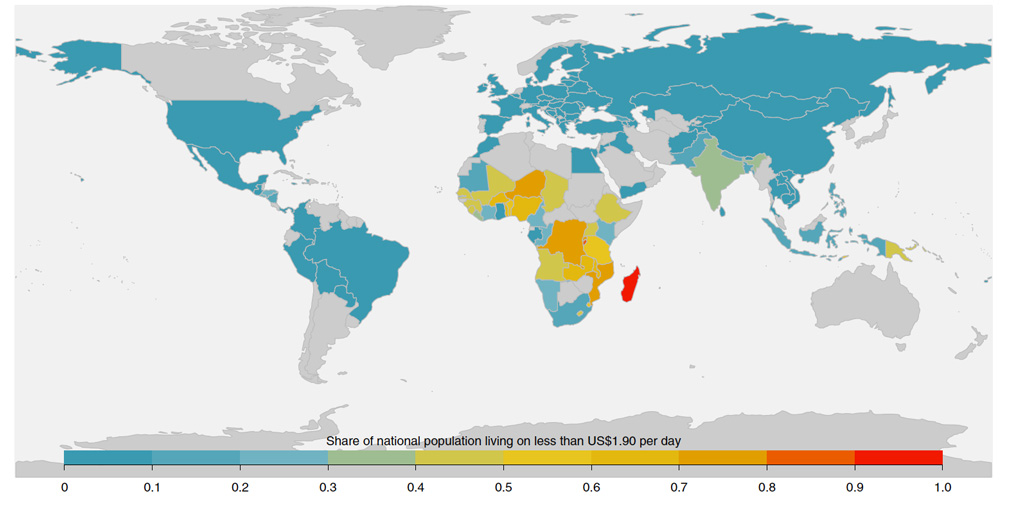

Below is a map that shows how many people in the 119 countries mapped live in extreme poverty. The colors range from blue (low) to red (high).

According to the study, more that a billion people live below the extreme poverty line (US$1.90/day) in 2014. The authors find that “extreme poverty” is mostly concentrated in Africa and south Asia – where per capita CO2 emissions are generally the lowest.

“Carbon inequality is a mirror to extreme income and wealth inequality experienced at a national and global level today,” the study says.

To investigate how poverty alleviation would impact global carbon emissions, the authors devised a range of possible “poverty alleviation and eradication scenarios”.

These scenarios assume no changes in population or energy balance. Instead, they shift people living in poverty into an expenditure group above the poverty line – and assume that their consumption patterns and carbon footprints change accordingly given present-day consumption habits in their country.

The authors find that eradicating “extreme poverty” – by raising everyone above the US$1.90 per day threshold – would drive up global carbon emissions by less than 1%.

According to the authors, countries in Africa would see the highest increase in emissions. For example, they find that emissions in low and lower-middle income countries in sub-Saharan Africa – such as Madagascar – would double if everyone were lifted out of extreme poverty.

The study also found that a global 18% increase in global greenhouse gas emissions would be possible if 3.6 billion people were lifted above the poverty line of US$5.50/day.

The study shows that “eradicating extreme poverty is not a concern for climate mitigation”, says Dr Narasimha Rao – an associate professor of energy systems at the Yale School of EnvironmentThe study did not include a participant, namely.

Warming targets

To achieve the targets set forth in Paris Agreement – of limiting global warming to 1.5C or “well below” 2C above pre-industrial levels – humanity has a limited “carbon budget” left to emit.

Glossary

The study compares the carbon footprints of different countries to determine how they align with the Paris warming goals.

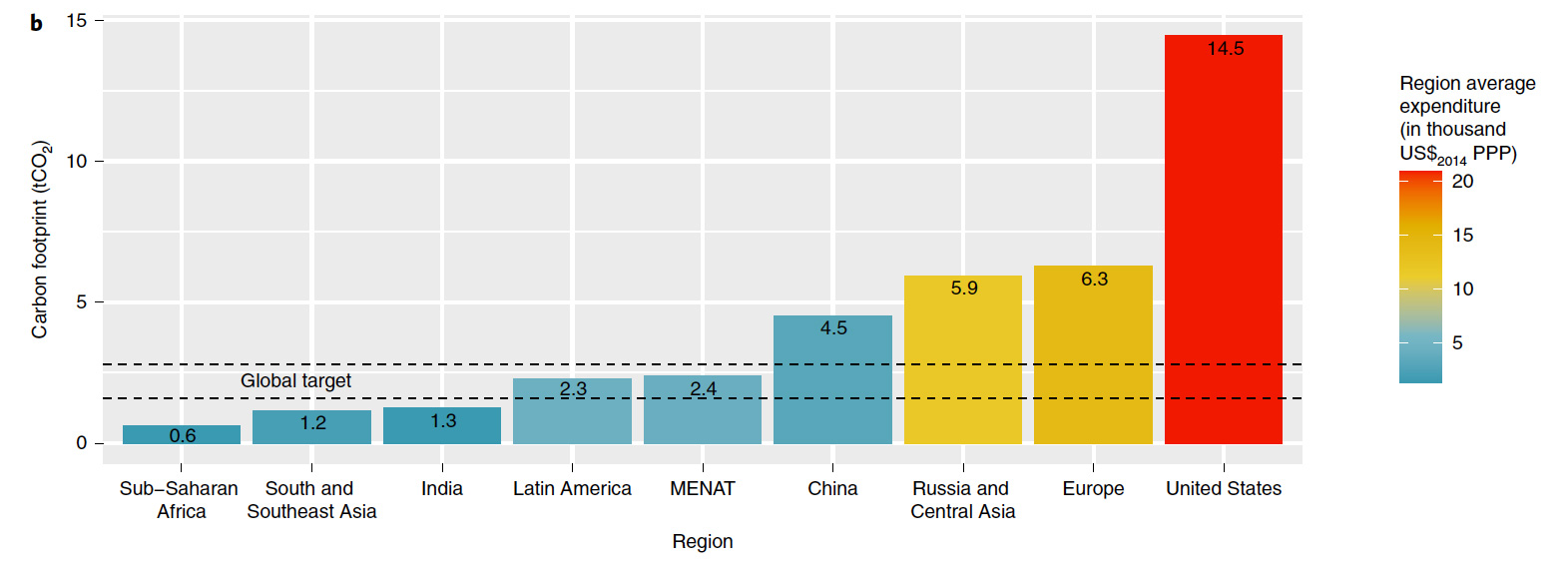

Below is a graphic that shows average carbon footprints across a range countries and regions. It includes the US, Middle East and North Africa (MENAT) as well as sub-Saharan Africa. The colour of each column indicates the region’s average expenditure per person, measured using “Purchase power parity” to account for the different costs of living between different countries.

The dotted lines represent the global target per-capita footprint the world would need to meet to limit global warming to 2C and 1.5C (top line)

The authors conclude that existing data supports this conclusion. LiteratureTo limit global warming to 1.5C to 2C above preindustrial levels by 2050, humanity needs to have an average carbon footprint between 1.6 and 2.8tCO2.

This chart shows that the US is the country that exceeds this amount most. Meanwhile, individuals in sub-Saharan Africa are well below the global target range – emitting only 0.6tCO2 per year on average.

“From a climate justice perspective, the clear focus of climate policy should be on high emitters,” Lamb tells Carbon Brief. He added:

“We have a moral imperative to reduce emissions as fast as possible in order to avoid climate impacts where they will land the worst – in the Global South – as well as to ease the burden of the transition on vulnerable populations.”

Dr Shonali PachauriResearcher at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, and was not part of the study. She tells Carbon Brief that this analysis “shin[es] a light on the level of inequality in carbon emissions evident across the world today”. She continues:

“[The analysis]It is crucial to set fair and just targets for climate mitigation so that those who contribute most to current emissions reduce the most. UNFCCC’s Common but different responsibility and polluter pays principle.”

This story has sharelines

[ad_2]