[ad_1]

India, along with many other countries has made ambitious commitments to restore forests to combat climate change. However, it is not clear what this goal looks like in practice.

Our study, published in Conservation Letters, uses detailed spatial mapping to estimate how much land is available to be reforested in India, which regions would be most appropriate and how reforestation could contribute to meeting the country’s climate goals.

Reality is very different. Restoring forests on available land – that is, land not currently used for anything else – achieves only 10% of what India has pledged under the Paris Agreement.

Combining tree-planting with agriculture – known as agroforestry – can make a big difference. The potential to reduce emissions would still not be more than a quarter the amount that India has committed to by 2030.

Why is India prioritising forest rehabilitation?

Most of the pathways to meeting the internationally agreed climate targets require the restoration of forests to remove carbon from our atmosphere. The following is the a list of recommendations. 100 nations pledge to “halt and reverse forest loss” by 2030 at COP26 DecemberThis landmark achievement was hailed by the world as a major step towards limiting global warming below 1.5C.

Many countries have made it a priority to restore large areas of forest as part of their environmental policies. Contributions that are determined by the nation. India aims to expand forest cover from 23% to 33% of its land area by 2030, creating an “additional (cumulative) carbon sink of 2.5-3bn tonnes of CO2-equivalent (GtCO2e)”.

There are many Global analyses of high profile importanceThere are hundreds of millions of hectares of land worldwide that could be used for forest restoration. However, these assessments and pledges don’t address the fact land is often already being used for other purposes.

These global estimates can also overestimate forest restoration’s true potential by including areas that may be ecologically unsuitable, such as natural grasslands or savannahs, as well as agricultural or pasture lands where forest recovery could endanger future food security.

Mapping India’s forest opportunity

We examine the potential to restore forests in India through our study. India is the seventh largest country on the planet, covering 3.3m sq km (km2). Expanding forest cover by 10% of the country’s land area is, therefore, no small task.

We calculate how much land in India can be reforested, where it is located and how much carbon sequestration that could be achieved. We focused on areas where natural forest can be sustained without compromising ecosystems, or threatening food security.

The first problem is that India’s climate is very diverse and not all climates are suitable to natural forest regeneration.

We used a machine-learning framework to define a “bioclimatic envelope” of where forests in India could be sustained, using a variety of climatic, topographic and soil data as predictors.

Although this study has been done before on a global scale, it is the first to be done in India with a dataset of more 11,000 GPS-tagged locations where the presence or absence of forests was verified on the ground.

Our analysis shows that there are just over 1mkm2 of land in India that could support forests. This leaves 0.6mkm2 of unforested land which could support new forest cover, after excluding the existing forest area.

This envelope does not take into account the variety of land uses in India. So, we then used a recent high-resolution national map of Indian land cover to exclude wetlands and native grasslands, woodlands and savannahs – all of which can harbour important biodiversity.

Of the amount of land that remained as potentially suitable for restoring natural forests, 74% is currently being used for agriculture – either to grow crops, raise livestock or to practise jhum (or “shifting agriculture”, a form of crop-growing predominantly practised in northeastern states).

Excluding land used for agriculture, as well as settlements and built-up areas, this left only 16,000 km2 of unused land in India that is immediately available for forest restoration – less than 0.5% of the country’s area.

If these areas could all naturally regenerate, we calculated that they could sequester about 61m tonnes of carbon (MtC) once mature – less than 10% of India’s 2030 pledge.

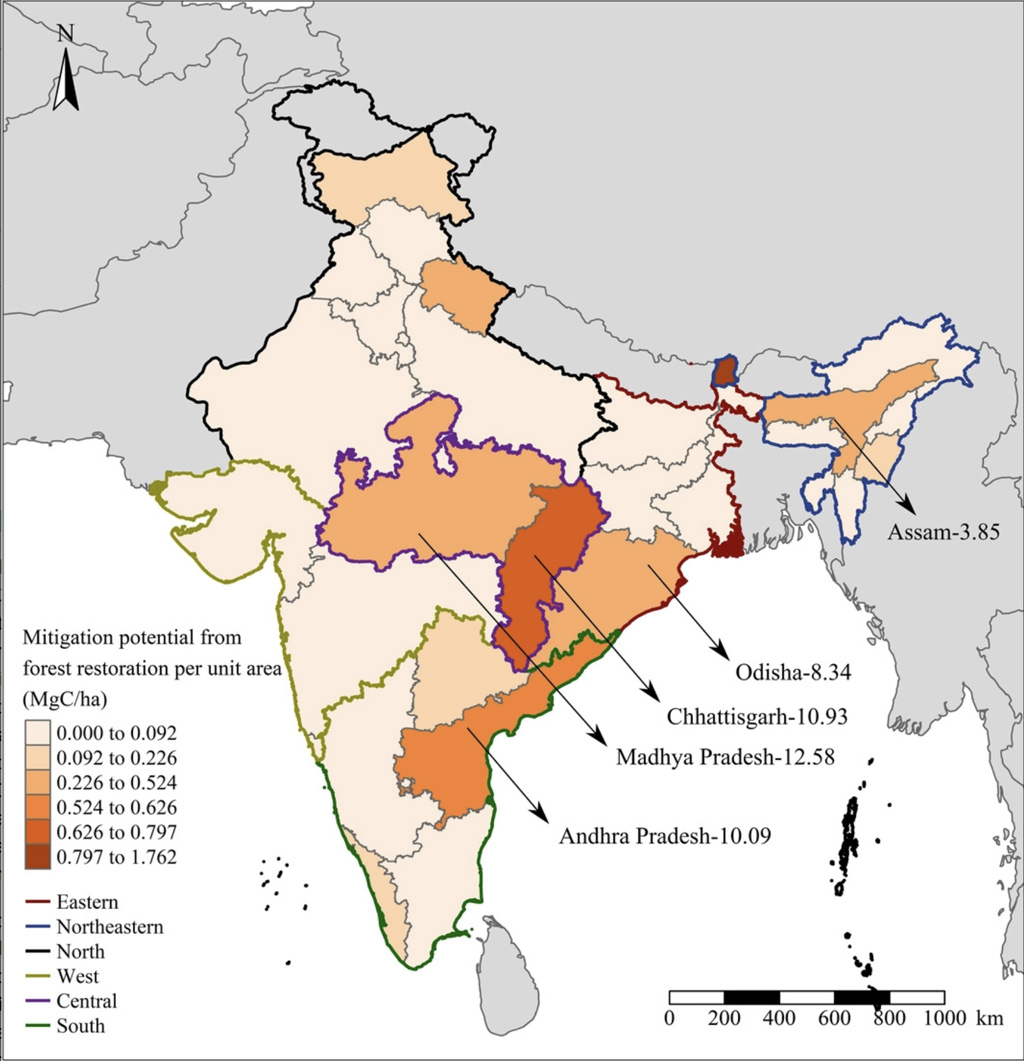

This land is also unevenly spread across India. The map below shows the amount of carbon that could be drawn down in different Indian states per unit area of restored forest – known as the climate change “mitigation potential”. The greater the mitigation potential, the darker the orange shading. As you can see, the largest opportunity to restore forests lies in the central and eastern regions of the country.

Forest restoration must be considered in relation to existing land uses

Because most of the potential for restoring forests in India is on land that is currently being used for agricultural purposes, agroforestryThis is one solution.

Agroforestry is the practice of integrating trees into crop and livestock agricultural systems and has been widely promoted in India as a way of supporting farmers’ livelihoods as well as improving environmental quality. India was the first country worldwide to adopt agroforestry. National Agroforestry Policy2014

We used data from real agroforestry practices across India to calculate how much carbon could have been stored if all farmland within the forest area was converted to agroforestry. We calculated that agroforestry could draw down an additional 98MtC from the atmosphere cumulatively – more, in fact, than restoring forests alone.

This is only a rough estimate. Agroforestry can be described as a wide range of agricultural systems that have different levels of tree cover and different carbon storage capacities. However, it’s enough to illustrate the scale of contribution that agroforestry could make.

Add the two together and that’s an additional 159MtC taken out of the atmosphere by India’s agroforestry expansion and forest restoration projects. This is still less than one quarter of the 2.5-3 GtCO2 – equivalent to 700-800Mt of carbon – that the government has pledged by 2030.

Making progress

Our study demonstrates the complexity of changing land uses on a large scale. In particular, global estimates tend to underestimate climate change mitigation potential in countries with large agricultural holdings. Our analysis also highlights how important it is to have local information about land-use.

Our findings indicate that forest restoration cannot be a key strategy to help India meet the Paris Agreement’s goals. We also believe that significant greenhouse gas emission reductions will be required by other sectors, especially energy.

Above all, our study emphasises that India’s climate goals require forest restoration strategies that work with existing land uses and the people who live and rely on that land, rather than replacing them.

We recommend that governments and researchers not only focus on the area available for forest restoration or agroforestry but also on social and cultural dimensions. These include issues such as forest governance, land tenure, historical land use, and approaches that can be reconciled with the needs of land users.

Gopalakrishna, T. et al. (2022). Current land uses restrict climate change mitigation potential forest restoration in India. Conservation Letters. doi:10.1111/conl.12867

This story has sharelines

[ad_2]