Americanresearcher Denise Mitrano received the Swiss National Science Foundation’s highest honor for her work in micro- and nanoplastics. Her new tracking method could indirectly aid in reducing plastic pollution.

This content was published at 09:00 on December 18, 2021.

Bern-based journalist from Ticino. I write about scientific and sociological issues through reports, articles and interviews. I am interested both in energy, climate change, migration, and human rights in general.

More from this author

| Italian Department

How much plastic do we put in our water and food every day? During a meeting at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH Zurich), that’s the first question Denise Mitrano asks me. I expect a reply along the lines of “a lot” versus “too many.” The truth is, however, more complex.

“Before it can be determined how much plastic is in a glass, or on a plate of food, we must measure it,” says the geochemist assistant professor. “Plastic particles can escape our current analytical tools because they can be extremely small.”

Women in Science

Switzerland has fewer women scientists that other European countries. The percentage of women professors in Switzerland is 23%, and it is even lower for the natural and technical sciences.

The Covid-19 pandemic may have further restricted women’s scientific work. A Swiss research team recently analyzed thousands of studies published between January 1, 2018, and May 31, 2021. This analysis revealed that women were less likely to be listed as lead authors during the first wave. Researchers believe that women researchers may have struggled to balance work and family during lockdown periods. This could explain why they published fewer articles compared to their male counterparts.

End of the insertion

This innovative tracking method could open new doors. Mitrano’s method allows you to track how tiny nanoplastic fragments spread through water, soil, and living organisms.

She cites her previous research as an example of how she said, “I’ve always wanted solutions to problems.” I was inspired to measure metal nanoparticles using methods I have developed.”

Plastics in wheat

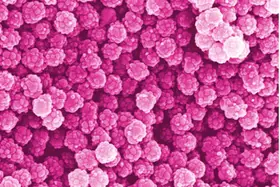

Mitrano’s solution is to chemically add metals to plastic nanoparticles. These are inert and precious metals such as indium or palladium that act as markers. This means that nanoparticles can be seen. “The advantage is that they are visible. [the metals]Plastic can be measured more accurately and quicker than plastic.

This process was used to test the effectiveness of a wastewater treatment plant in removing microscopic particles from water. Mitrano says that 95% of microplastic fibers and nanoplastics have been removed.

However, this doesn’t solve the problem of plastic contamination. The scientist points out that nanoplastics build up in sewage sludge. They are incinerated in Switzerland, but they are used in other countries to fertilize fields.

Mitrano also investigated whether a drinking-water treatment station can purify nanoplastic-contaminated water. To do this, she recreated some stages of purification atZurich’s facility. She says that slow filtration with sand filters was particularly effective.

Another experiment was to see how plastic is absorbed by wheat plants grown in hydroponic (aboveground) systems. The nanoplastics reached the leaf and the plants responded by increasing their carbohydrate content. Mitrano states that this is a defense mechanism. However, we didn’t observe any decreases in chlorophyll production, or toxic effects on the cells, even at high amounts of plastic.

One credit card per week

Around 80% of microplastics are formed from the degrading of larger pieces of plastic already present in the environment such as bags, fishing nets, plastic films used in agriculture, construction, and other uses. The 20% remaining is released directly into the environment, such as through tire abrasion and clothes-washing.

According to the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, 615 tonnes of microplastics end-up in soil and water each year in Switzerland. There have been reports of plastic residues in large lakes, lowland rivers, glacier meltwater, and Alpine streams.

Plastic is everywhere, even in our environment. According to estimates, five grams of plastic is consumed each week, which is equal to the weight of a credit-card. A 2019 studyExternal linkThe Australian University of Newcastle, which was commissioned the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Consuming bottled water and shellfish, beer, and salt is the best way to absorb the most plastic particles.

Although there isn’t any scientific evidence to support this, microplastics could pose a risk to human health. “We know plastic is a persistent material, and that it is found in many ecosystems. Mitrano adds that there are still many unknowns.

There are many types of plastics available, each with its own characteristics. Manufacturers also add stabilisers, additives, and other chemicals to plastics. Mitrano emphasizes the importance of determining which aspects of plastic pollution can be toxic to humans and their natural habitats as well as the possible consequences for the environment.

Award for outstanding research

Mitrano’s innovative method will help reduce plastic pollution, at most indirectly. She states that while it is always a question about the costs and the benefits, if we can show farmers that the plastic film they use in their fields has a significant negative impact, they may choose biodegradable products.

She adds that science can also be used to guide industry in identifying the most problematic materials so that companies can find solutions.

Mitrano was awarded 2021 Marie Heim-Vgtlin PrizeExternal linkFor her research on microplastics.

“I didn’t anticipate this,” says Mitrano. It’s a great honor.”

“The award shows the importance and promotes the position of women scientists.”

Denise Mitrano

Denis Mitrano was raised in New Hampshire, USA. She obtained her PhD in geochemistry at Colorado School of Mines. She then moved to Switzerland in 2013. She has worked at the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, (Empa), and at the Swiss Federal Institute of AquaticScience and Technology, (Eawag), where her work on nano- and microplastics began. Denise Mitrano, assistant professor of environmental chemistry for anthropogenic materials, ETH Zurich, since 2020.

End of the insertion

Translated from Italian