[ad_1]

A Debate in the House of Commons on 19 January, led by a group of MPs known as the “atomic kittens”, suggested nuclear energy can be a panacea for all ills – including a solution for the climate crisis and the gas crunch. The facts support this conclusion.

Isn’t nuclear energy a no-no after Chernobyl and Fukushima?

It is clear that disasters reduce the desire for nuclear power among policymakers and the public.

Before the 2011 Fukushima incident Japan had planned to increase its dependence on nuclear with half of the country’s electricity forecast to come from the energy source by 2030, compared with around a third in 2010. But after Fukushima, the Japanese government took all 54 of the country’s nuclear plants offline for safety checks. By 2012, the share of nuclear in the country’s electricity mix had dropped to 14 per cent, and by 2020 it was down to less than 5 per cent. Germany was one of the countries that decided to completely eliminate nuclear power after the disaster.

Today, there are very few new nuclear construction projects, even in countries like France or the US, whose energy systems are heavily dependent on the technology. Also, the number of operating reactors is low. Receipt globally.

Are there any countries investing heavily into nuclear?

A key reason that the number of new plants under construction is still low is not only safety concerns but also rising costs. Since 2011, nuclear power construction has been increasing steadily. Costs worldwideThe number of people who have been displaced by the wars has doubled or tripled. China is however notable for its nuclear ambitions. The country is PlannedAt least 150 new reactors will be built over the next 15-years, more than any other country has built in the last 35 years. However, cost could eventually change the direction of travel.

Other countries, such as the UK and the US, see limited roles for nuclear power in their response to climate change. The UK government’s 2021 budget net zero strategy talked about “cutting edge new nuclear power stations”, and plans to launch a £120m Future Nuclear Enabling Fund.

There are some big nuclear power stations on the cards – think Hinkley Point C or Sizewell C in the UK. Many nuclear enthusiasts, including many UK MPs, are excited about the so-called small modular radioreactors (SMRs). They are the answer for all energy and climate problems, according to the hype.

What is a small modular reactor (SMRT)?

As with many things to do in nuclear, there is no consensus. “Big is best” has, until now, been the mantra in the vain hope of keeping costs down by creating economies of scale. A large nuclear power station can be understood to be between 1,500 and 1,700 megawatts. A SMR reactor would be 300 MW or fewer. The offering from Rolls Royce – the major player in the field in the UK – would have the capacity to generate 470 MW of energy. A similar reactor would take up about the same area as a house. Two football pitches.

Rolls Royce, and companies working on the technology in other countries, argue that smaller solutions can be constructed more cheaply and come online more quickly as they can be built in a factory, transported in modules and fitted together “like meccano”, said Rolls Royce’s Alastair Evans. Large nuclear plants can be built completely on-site. The idea is that modules could then be mass-produced. But, nothing is yet rolling off conveyor belts. A 35 MW is the only SMR that is up and running anywhere in the world. Floating nuclear power plantRussia

This sounds very interesting. SMRs: Are they the solution to climate crisis?

Unlikely.

“To meet the requirements of the sixth carbon budget, we will need all new cars, vans and replacement boilers to be zero carbon in operation by the early 2030s,” Virginia Crosbie, a Conservative MP from Wales and the original self-proclaimed “atomic kitten”, enthused to fellow MPs. “We must quickly move away from generating that electricity from fossil fuels… Nuclear power, which has been a neglected part of our energy mix, can bridge the gap.”

However, there is no magic bullet for the climate crisis. Renewables in combination with other technologies seem like a better and cheaper solution.

For nuclear, power stations that have been online and are safe should remain online for the time being as they are a low-carbon option.

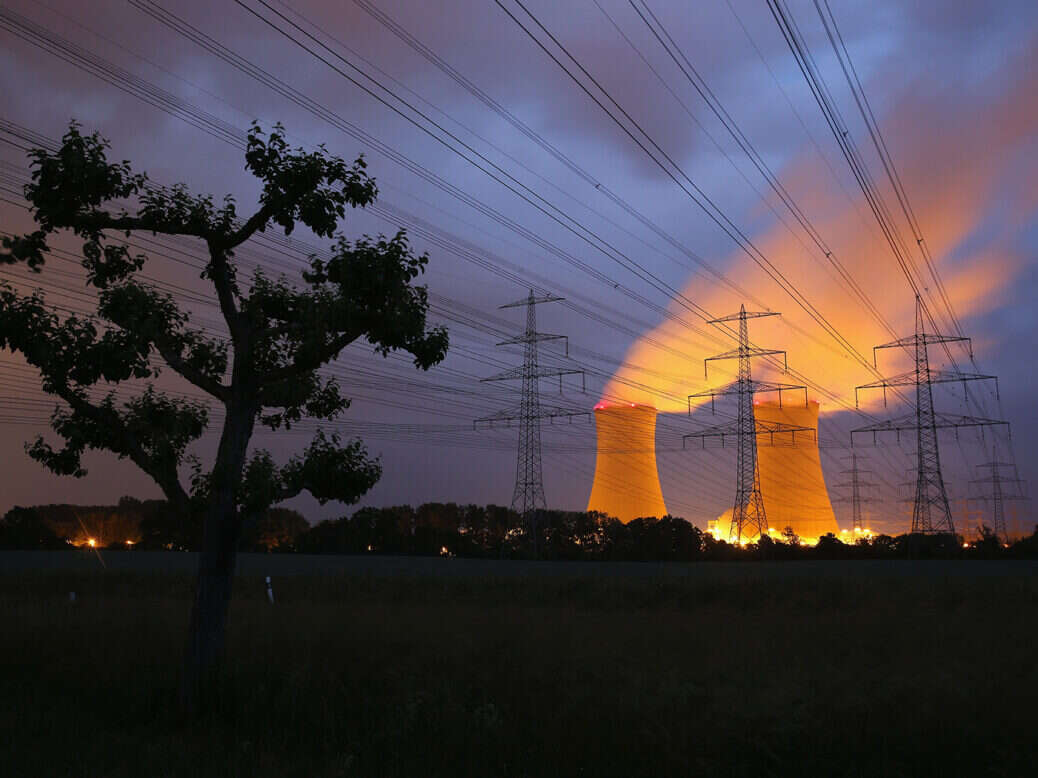

However, traditional, big nuclear projects look likely to provide only a sliver of the world’s electricity in the future. They are expensive to build, take a long time to construct, and are often plagued by technological problems. Paul Dorfman from University of Sussex highlighted that they should be built close to the ocean or large rivers to cool them down. France has already experienced to CurtailThe heatwaves and droughts that are causing a decline in nuclear power output, as well as the rising cost of electricity, have a direct impact on nuclear power production. This is only going to get worse with climate change. Greater storm surges and eroding coastlines also don’t make the prospect of building by the sea any easier.

These issues are few solved by SMRs.

“The modular construction helps to cure issues that have been experienced with past nuclear projects, such as financing, long construction timelines and cost,” said Crosbie. Many energy experts disagree.

“The latest economic estimates available for SMRs are still quite expensive relative to other ‘clean’ energy alternatives, and it would be pure speculation to assume that will change dramatically until the concept has been more proven,” said Mike Hogan from the not-for-profit Regulatory Assistance Project.

Most importantly, we must reduce global emissions by 45 percent by 2030 in order to reach net zero by 2050. AccordingThe International Energy Agency (IEEA) is responsible for ensuring that the The UK governmentIt has committed to decarbonising its domestic power system by 2030.

Take the UK for example. Hinkley Point C has been delayed, and will not go online until summer 2026. Sizewell C, should it be built, wouldn’t produce electricity until the 2030s. SMRs could be up and running as soon as 2028, claimed Crosbie, but even Rolls Royce says it wouldn’t have a SMR online until around 2031.

“Once commercialised, SMRs could be out of the door quicker than traditional power stations. But the designs still need to get licensed, factories need to be built, orders placed, projects financed, etc,” said Hogan.

It is difficult to see how technology that will be operational only after the UK’s power grid is declared carbon-free can contribute to climate change in the next ten to fifteen years. The situation is similar worldwide.

SMRs would still have to answer other questions about traditional nuclear power stations like the difficult issue of waste.

What is the solution? Renewables, renewables, and more renewables.

The short answer is yes. The costs of solar, wind and storage Continue to fallGlobal renewable electricity capacity is expected to increase by more than 60% by 2026, reaching a level that would be equal to the global total power capacity for fossil fuels and nuclear. The IEA says.

Some argue nuclear can be a clean back-up option for when the wind doesn’t blow and the sun isn’t shining. However, there are many other options available, such as demand response (for instance, plugging in an electric car when there’s lots of power and not turning on your washing machine if the system is under strain), large storage and interconnections among different countries.

The final word?

Craig Bennett, chief executive officer of the Wildlife Trusts, summarized the general mood among those less enthusiastic about nuclear than Crosbie or her fans:

“If successive governments had given even half the love and attention they afford to nuclear power to scaling up home insulation, energy efficiency and smart storage technologies, it’s likely we wouldn’t be facing current challenges around energy and household bills, and we would have done a lot more good for the climate and nature.”

If nuclear is to play a role in the climate crisis, the industry – big and small – will have to do a much better job of delivering what it claims it can, on time and at a competitive cost.

[See also: