[ad_1]

What happens to local communities, workers, and businesses that rely on them as the world shifts to renewable energy?

At the global summit on climate in Glasgow this week, business, government, as well as civil society leaders will be present discussed how a “just transition” can help address the social challenges ahead. The term “just transition” is about prioritising decent work and quality jobs for displaced workers as coal mines, oil refineries, power plants and more, are rapidly phased out.

We explain why in our recent researchOn paper, the idea for a just transition should be expanded. To meet the growing demand for minerals in clean energy infrastructure, new mines are needed. These mines could also be accompanied by enormous impacts, including new forms and levels of inequality, social exclusion, as well as impacts on land, natural resources, and other issues.

If we fail to balance the social impacts of climate change with responsible climate action, we risk substituting one kind of harm for another – and this would be a disaster of another kind.

Shutterstock

Justice in the energy transformation

The world will need a lot of it. minerals and metalsClean technology includes iron ore for wind power infrastructure and copper for electrification systems. Nickel is also available for battery storage.

The mines for these energy transition minerals are likely to be deeper, lower grade, more energy and water-intensive, and built on Indigenous peoples’ lands. They will produce more mine debris and be more hazardous. tailings(mining residue).

In addition to causing environmental damage, installing new renewable energy projects such as solar or wind farms can also result in them being installed. social and environmental impacts. These projects require large areas of land which may limit the rights and freedoms of Indigenous peoples.

Continue reading:

Why most Aboriginal people have little say over clean energy projects planned for their land

The International Energy Agency predicts that the combined revenues from critical materials will amount to approximately $1.5 billion. overtake fossil fuelsBefore 2040. Governments will be under pressure to attract this high demand. investmentApprove and support new mines.

This will put to the test community consultation and processes for obtaining approvals. free, prior and informed consentFrom Indigenous peoples.

The potential for expensive disruptions from large-scale new mines is also present. mining legacies. The historical problemAbandoned mines and environmental clean-up are a problem worldwide. For decades, mined rocks can seep acids and heavy metals into the waterways. This problem could be exacerbated by the construction of more mines.

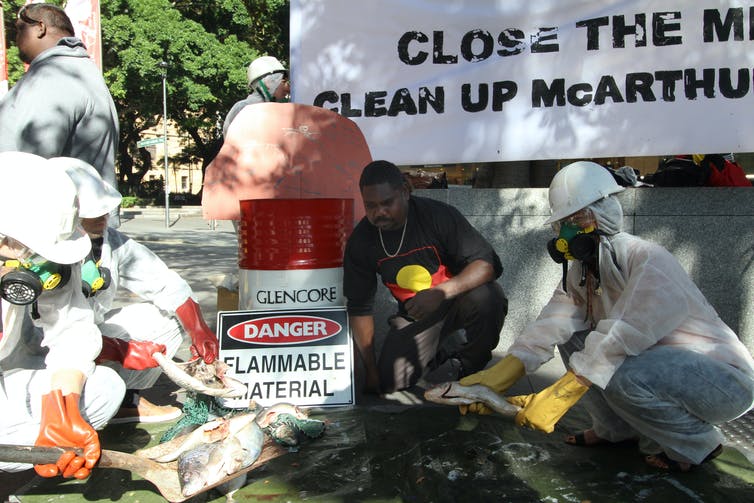

We’ve already seen big impacts from mining energy transition minerals in, for example, Australia. McArthur River’s Traditional Owners are still involved. opposeThe environmental and social impact of lead-zinc mining on the nearby Borroloola community, including the potential for leaking of potentially harmful substances harmful contaminantsAnd smouldering waste rock.

AAP Image/Essential Media

Some countries are trying to secure the materials that they need to transform their energy systems. China is one example. monopolyProduction of rare-earth elements, such as neodymium which is essential for renewable technologies such as wind turbines and electric cars.

Uncertainty in the supply of these minerals could lead to new opportunities geopolitical conflictsThis could put an end to open competition on global commodity markets, and increase pressure on the future of open competition. This could reduce transparency and increase human rights risk in supply chains.

To avoid these types of problems, a smooth transition must be made sacrifice zonesIn remote mining communities and along global supply chain networks in the name climate action.

AP Photo/Darko Vojinovic

Expanding the idea is gaining traction

The first proposal for a just transition was made by the trade union movementIt was in the 1970s. It was also mentioned as a preamble in the Paris AgreementIt was reaffirmed in 2018 Silesia Declaration.

Continue reading:

Land, culture, livelihood: what Indigenous people stand to lose from climate ‘solutions’

This week’s Glasgow roundtable was a significant moment, as it brought the full scope for a just transition to the COP agenda. The roundtable was opened by the former Irish president and climate justice campaigner. Mary RobinsonThe energy transition must uphold human rights, gender equality, and the rights of workers everywhere.

Also, Sharan BurrowGeneral Secretary of International Trade Union Confederation. saidClimate action should allow workers and communities to thrive by creating new jobs in a socially inclusive environment. green economy. This is what underpins calls to a Green New DealAll over the world

And the Institute for Human Rights and BusinessThis week’s roundtable was convened by. plans to hostA just transition event at each future COP.

What are we to do?

It’s taken decades to get the social impacts of climate change on the global agenda. Now we must put greater focusOn the social consequences of climate action.

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human RightsThis is a good place to start. This is an essential instrument to help all companies – mining, renewable technology and finance – take responsibility for their social and environmental impacts.

Continue reading:

COP26: a four-minute guide by a climate scientist

These principles require that businesses follow them. human rights due diligenceTo ensure that workers, communities and other people in the renewables supply chain are not harmed. Companies must understand the rights of others and take appropriate action.

This is similar to the idea climatising human rightsIn this country, powerful parties are held legally responsible for their climate actions and impacts.

The European Union is currently considering mandatory human rights due diligence laws, compelling businesses to assess the social and human rights impacts of climate action whether they’re extracting minerals or building renewable energy projects. This would be a significant step towards climatising the rights of humanity.

These initiatives are a platform to promote change. What’s missing is real action to carry them forward and achieve justice across all aspects of the energy transition.

That’s why tracking progress will be vital. The World Benchmarking Alliance has launched a process for just transitions assessment toolIt was published in December and its findings were shocking. It revealed that high-emitting businesses are not using their influence in order to protect people and manage social impacts. advocateFor a smooth transition.

This must change as the increased rate of extraction due to climate change stress will lead to an increase in extraction. new patternsOf harm.

This story is part of The Conversation’s coverage of COP26, the Glasgow climate conference, by experts from around the world.

The Conversation is here to help you understand the climate news and stories. Read more of our U.S.And global coverage.

[ad_2]

Source link