[ad_1]

Until now, the government’s approach to Climate actionThe policy architecture has been the focus of this work. This work is vital, but it’s more about rearranging possible futures, less about emissions reductions in the near term.

The Emissions Reduction Plan (now available)ERP) was supposed to shift gears, to get real about urgent climate action – and it partially achieves this, but only partially.

Budget 2022 will include some additional spending, but the majority of the expenditures are covered. Climate-relevant funding of $2.9 billionThe ERP was also confirmed. It shows a sensitivity to electoral constraints on transformation, but less a sense of reality about what decarbonisation actually requires.

There are important steps forward. Resourcing for Māori involvement in climate policy is long overdue. It is also beneficial to integrate education and social support.

In this sense, ERP is a minor victory. Policy scholars and public sector officials have been championing the ideal of Joined-up governmentWithout ever putting it into practice. The ERP is unique and even unheard of because it takes a whole-of government approach, bringing together all core government departments into a 340-page report.

Getty Images

Time is crucial

This interconnectedness is what makes ERP so great. Nature-based solutions – that is, enhancing natural ecosystems to address multiple challenges – emerge as a strong connective theme, not only between various sectors, but also across the National Adaptation Plan and Biodiversity Strategy/Te Mana o te Taiao.

This is also true for infrastructure and planning that are clear about the overlaps of opportunities to reduce emissions from multiple sectors.

Similarly, the rising theme of the “bioeconomy” sheds new light on the importance of forestry, not only as a supplier of timber and carbon removals, but also as feedstock for bioplastics and biofuels to substitute crude oil.

Continue reading:

New Zealand could be pushed into extinction if it does not have a better plan.

But instead of investments to make this happen, the ERP promises a bioeconomy and circular economy strategy that won’t be complete until 2025. This is the overriding character of the document, where a large proportion of “actions” begin with the words “explore” or “investigate”, or lapse into research, baseline setting and elongated work programmes.

Even well-known ideas like congestion charging are being delayed. The government has investigated this policy for more than a decade, but the ERP only confirms it is “considering progressing legislative changes to enable congestion charging”.

The ERP was the moment to make a decision. The failure to do so leaves a lingering suspicion that the ERP’s new slew of pledges may face a similar fate.

Acceptability is better than ambition

There are plans. Plans for plansHowever, there is still a lack of strategy. For example, the Energy sector policy is technology-neutral and does not narrow down on priority areas like geothermal energy. Natural advantagesPotential for global impact through your expertise and knowledge.

Even in the absence of a central strategy for energy, such opportunities are already evident. Research, development, deployment all take time. Strategic decisions need to be made immediately, and not delayed for later in this decade.

The proposal of “climate innovation platforms” might provide the vehicle for strategic innovation, but only if properly resourced. The ERP is a compromise-oriented system that favors acceptance over ambition.

Fortunately, however, the proposed Policy mix – along with an improved Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) – will take us quite some way.

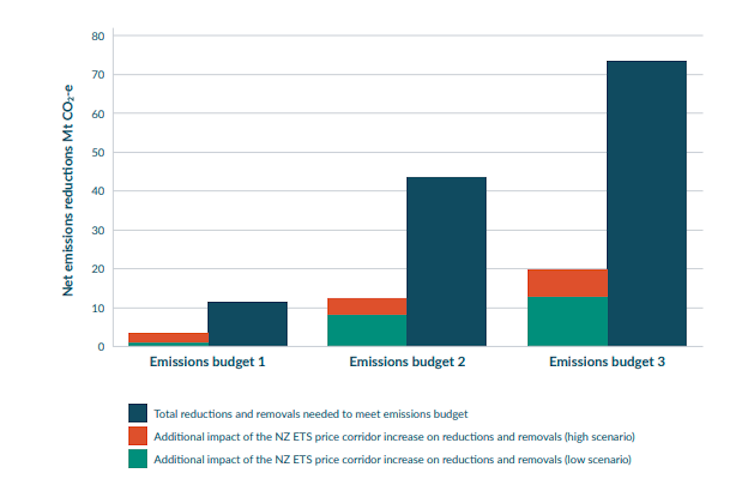

ERP emissions pricing

The total amount of new mitigation required to meet emissions budgets.

NZ Government

The NZ$69 Million Government Investment in Decarbonizing Industry (GIDITo accelerate industrial decarbonisation, the ) fund is being increased by nearly $680 million. This is a tenfold increase.

Transport includes $350 million to fund cycleways and public transport, 40 million to decarbonize bus fleets by 2035, $20million to decarbonize freight transport and $20million for a vehicle social lease scheme trial.

Agriculture is also the beneficiary of $710 million from ETS auctioning revenue for agri-tech and research – arguably unfairly, given that agriculture currently sits outside the ETS.

Continue reading:

With seas rising and storms surging, who will pay for New Zealand’s most vulnerable coastal properties?

Dependence upon cars

These initiatives are overshadowed by the scrap-and-replace program, which aims to subsidise people into electric cars (EVs). It is already a hot topic. The Empirical recordFor scrappage schemes in other countries, such as the US Cash for Clunkers program, it is common to conclude that emissions reductions will not be significant despite high investments.

New Zealand’s scheme may reduce more emissions than other schemes because replacement cars must be EVs/hybrids. However, low-income households may not have the means to pay the difference due the high cost of EVs.

Continue reading:

Is the budget another missed opportunity to get more New Zealanders off their cars?

The scheme also risks perpetuating the dependence of cars that makes transport mode shift so difficult. The $569 million dedicated to scrap-and replace is much greater than the $350 millions committed to cycleways or public transport.

It is hard to resist the conclusion that a scrappage scheme – for all the flak it will receive from efficiency-minded economists – was perceived as more politically palatable than getting people out of cars.

Continue reading:

IPCC report: How New Zealand could reduce its emissions faster and rely less heavily on offsets to achieve net zero

The political challenge

The ERP is projected to drive enough change to meet New Zealand’s 2030 Paris Agreement pledge. Part of this effort will include the purchase of emission reduction credits on international carbon market, at potentially high prices.

A high reliance on paying for other countries to reduce their emissions reflects a hangover in the New Zealand government’s thinking, dating back to the Kyoto Protocol era. Deferring hard choices now by “planning more plans” might reduce the risk of backing the wrong technologies, but deferral is not without its risks either.

This speaks to the long-standing problem of treating global warming as a technical, scientific issue. Climate action, like all puzzles, will benefit from further analysis, evaluation, and discovery.

This is true for both elected and unelected officials. It is a way to look serious and even prudent while also avoiding important decisions and responsibilities. The slow-moving climate crisis is more appealing than the fast-moving pandemic. This opens up the possibility of dawdling.

Climate action was always about politics. The ERP practices the arts of acceptability but neglects the art of the possible – of making ambitious commitments and bringing the people along.