[ad_1]

Poverty, poor infrastructure and dependence on rain-fed agriculture are the main drivers of the ongoing food crisis in Madagascar, according to a new “rapid-attribution” study, while climate change played “no more than a small part”.

After years of below-average rainfall, southern Madagascar is now experiencing severe drought. more than one million peopleIn food insecurity. The World Food Programme has called the situation an “emergency” and warned that the drought “could spur the world’s first climate-change famine”.

But, there is a new way. attributionStudy, led by a team of researchers from the World Weather Attribution (WWA) network, finds that “while climate change may have slightly increased the likelihood of this reduced rainfall [over 2019-21], the effect is not statistically significant”.

The country has one of highest poverty rates in history, according to the authors. This is due to pest infestations as well as Covid-19 limitations that prevented people from migrating within the nation to find work.

‘Highly vulnerable to drought’

Madagascar is an Indian Ocean island nation. It is home to many people. extreme poverty, where more than 90% of the country’s 26 million inhabitants live on less than $1.90 per day. The island was ranked fourth in the world for chronic malnutrition in 2019 and had the lowest human capital index.

Agriculture is a mainstay of Madagascar’s economy, providing a livelihood for around 80% of its population. Most farmers rely on rain-fed crops and practice subsistence agricultureCassava, sweet potatoes, bananas, maize, bananas, and rice are some of the crops that can be grown on the island. However, the island has low yields and is not well-suited for growing sweet potatoes. not been keeping up with population growth (pdf).

Madagascar is home to subtropical climate. The country experiences a hot and wet season between November and February, while May and October are marked by cooler and drier conditions. Southern Madagascar is particularly dry and sees very little rain during the first few months. southwest and extreme south of the island are classified as “semi-desert environments”, typically receiving less than 800mm of rainfall per year.

Denis Bariyanga, operations coordinator for the Indian Ocean Islands cluster at the International Federation of Red Cross. Carbon Brief hears from him that communities in southern Madagascar are very vulnerable to drought.

“Communities in the south of Madagascar have always been vulnerable due to the semi-arid climate, the El Niño phenomenonThe poor access to different areas in this region of the country and their primitive agricultural methods are two reasons. While the drought has been categorised as prolonged and aggravated since 2013, the food-related issues have been emerging even before 2000 due to those recurrent moderate droughts.”

The World Bank says that Madagascar is “one of the African countries most severely affected by climate change impacts”.

Drought and food insecurity

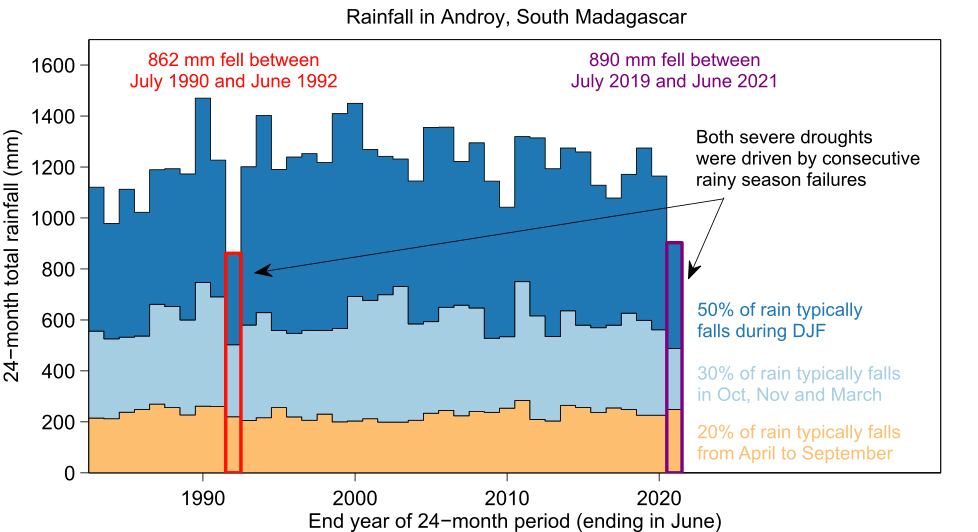

Southern Madagascar’s food crisis of 2020-21, which has pushed more than 1.14 million people into food insecurityLow rainfall over a 24-month span was the trigger. The study finds that the rainy seasons of 2019-20 and 2020-21 brought just 60% of “normal” rainfall to the region, driving “significant crop failure” and “famine-like” conditions across much of the region.

The plot below, taken directly from the study, shows 24-month rainfall amounts from the 1980s through the present. It shows the droughts of 2019-21 (purple) and 1990-92 (red).

The 2021 Summer Olympics will be held in June 2021. World Food Programme (WFP) announced that southern Madagascar was “experiencing its worst drought in four decades”, warning that 14,000 people were already facing “catastrophic conditions”. On 23 June, WFP executive director David BeasleyDistributed an appeal for help for Madagascar:

“There have been back-to-back droughts in Madagascar which have pushed communities right to the very edge of starvation. People are already dying of severe hunger and families are suffering. This is not due to war or conflict; it is because of climate changes. This is an area of the world that has contributed nothing to climate change, but now, they’re the ones paying the highest price.’’

Southern #MadagascarThe frontlines of climate crisis. These families did nothing to deserve the worst drought for 40 years. Yet, their lives have been devastated and thousands are in danger of starvation.

We must act NOW in order to save lives. pic.twitter.com/zGVV42rOFf

— David Beasley (@WFPChief) June 21, 2021

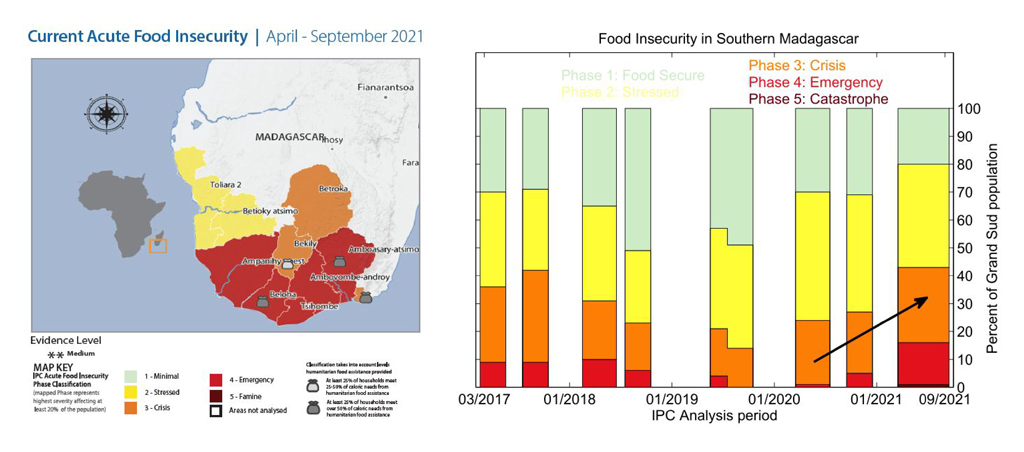

The plot below shows food security for southern Madagascar in April-September 2021. This is based upon a five-tier food security scale, where 1 (green) indicates “minimal” food insecurity and 5 (dark red) indicates “famine”.

“This year marks the first time that people have been recorded in IPC5 [the highest tier of the food security scale] since the methodology was introduced in Madagascar in 2016”, Bariyanga tells Carbon Brief. He added:

“The south of Madagascar depends on rain-fed agriculture. Since the region faced recurrent drought for several years, this had a devastating impact on access to food for communities… In an area where more than 80% of the population are dependent on agriculture, this [rainfall deficit] exerts additional pressure on the very lean resources available and leads to a deterioration in the nutritional situation.”

The WFP is open from mid-November to mid-December appealed again for “solidarity and funding”. The organisation has been supplying some 700,000 people on the island with food and supplemental nutritional products for pregnant and nursing women and children – but still found that that “close to 30,000 people in Madagascar will be one step away from famine by the end of the year, and some 1.1 million already suffer from severe hunger.”

🇲🇬 Madagascar is facing one of the world’s first famines driven by climate change, hunger experts warn.

🔴Families are now forced by the failure of crops to feed them insects and cactus leaves.

🚨 @WFPThis crisis is a warning to all of humanity. Here’s why you need to pay attention. 🧵 pic.twitter.com/u5vmvcxZ8i

— TRF Climate (@TRF_Climate) November 3, 2021

Drought can be attributed

Attribution is a fast-growing field of climate science that aims to identify the “fingerprint” of climate change on extreme-weather events, such as heatwaves and droughts. This study examines the effects of climate change on rainfall in southern Madagascar from July 2019 to Juni 2021.

To conduct attribution studies, scientists use models to compare the world as it is to a “counterfactual” world without human-caused climate change. This study aims to distinguish the “signal” of climate change in Madagascar’s rainfall from natural variability.

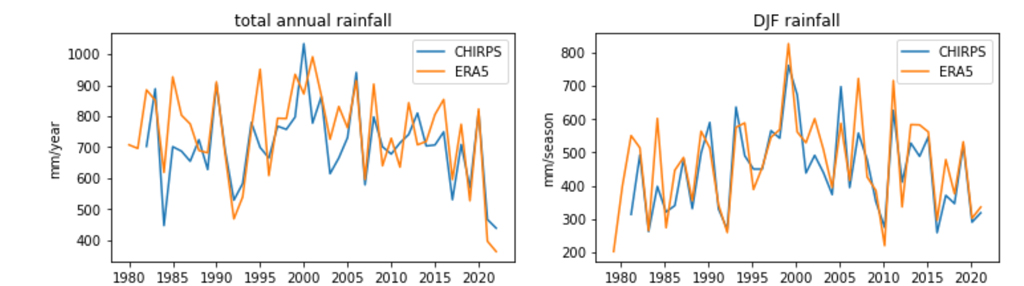

The plots below show the total (left) as well as wet-season (right), rainfall in southern Madagascar during 1980-2021. The lines indicate the CHIRPSRainfall dataset (blue), based on satellite observations and rain gauges, and the ERA5Reanalysis dataset (orange), which combines model simulations and observed data.

The study classifies the drought in southern Madagascar is a “1-in-135 year dry event” – meaning that in today’s climate, a drought of this magnitude would be expected less than once per century. Dr Friederieke Otto – a senior lecturer in climate science at the Grantham Institute for Climate Change and the Environment and co-lead of the WWA – tells Carbon Brief that this makes the drought “a rare event”.

However, as rainfall in southern Madagascar varies so much on a year-to-year basis, the study finds that climate change played “no more than a small part” in the drought. It concludes:

“The occurrence of poor rains as observed from July 2019 to June 2021 in southern Madagascar has not significantly increased due to human-caused climate change. While the observations and models combine to indicate a small shift toward more droughts like the 2019-21 event as a consequence of climate change, these trends remain overwhelmed by natural variability.”

Instead, the study highlights the “high pre-existing levels of vulnerability to food insecurity” in the region. The authors say that poverty, poor infrastructure and dependence on rain-fed agriculture are the main drivers of the drought, adding that the impacts were “compounded by Covid-19 restrictions and pest infestations”.

This is consistent both with previous research and the conclusion of the most recent study. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) sixth assessment report(AR6). Any perceptible changes of drought would only be apparent in this region if global mean temperatures exceed 2C, above pre-industrial levels.

(The results are still to be published in a peer reviewed journal. The methods used in the analysis were published in previous attribution studies.)

Complex extremes

The study notes that droughts are “comparably complex extreme events which depend on a number of climate and non-climate factors”, adding that this “poses challenges for their attribution”.

For example, explains Otto, droughts are more difficult to link to climate change than heatwaves because, while climate change is “really a game changer” for heat, the climate change signal for rainfall tends to be “small” compared to natural variability.

Another complicating factor is “event definition”. There are many ways to define an event. drought – including agricultural droughts that focus on soil moisture, and pluvial droughts that focus on surface and groundwater flows. This study focuses on hydrological drought – defined only by the amount of rainfall a region receives.

Otto explains that the researchers focused on hydrological drought because “from studies into similar climatic regions, we found that it is really rainfall that determines the drought”. She adds that the meteorological service in Madagascar, who collaborated with the WWA team on the project, also see hydrological drought as “the issue” in the country.

Get our free Daily BriefingOur digest of the past 24 hour’s climate and energy media coverage. Weekly BriefingFor a complete round-up of our content for the past seven days, click here Enter your email below.

Dr Nikos Christidis – a senior climate scientist from the UK Met Office who was not involved in the study, also highlights the difficulty in defining drought, noting that “this analysis provides useful information about the effect of human influence on rainfall, but not on other variables that also need to be considered so that we understand better the impact of anthropogenic climate change on droughts”.

Dr Peter StottShe is a science associate in climate attribution at UK Met Office, and was not part of the study. He tells Carbon Brief that this is “an interesting study by a strong group of researchers”. He added:

“I think a result of this importance – that climate change made a negligible contribution to the devastating drought – would benefit from confirmation from other studies including in the peer-reviewed literature.”

There have been many studies that show the severe drought in California during 2011-17. came to different conclusionsThe influence of climate change.

And Dr Tamara Janes – a Met Office climate scientist focusing primarily on international development in Asia and Africa – tells Carbon Brief that the study “helps to highlight the importance of understanding and building resilience to existing vulnerabilities”. She added:

“While the results of the study suggest that the current, devastating food security crisis in Madagascar cannot be significantly linked to observed human-induced climate change, it’s important to recognise that events such as these are likely to be exacerbated in a changing climate.”

This story has sharelines

[ad_2]