[ad_1]

Prime Minister Scott Morrison arrives at today’s opening of the United Nations climate summit with a 2050 net-zero emissions target born from a painfulPolitical process

Friendly nations will feel a sigh relief, as they are freed from the awkward task to call out Australia on its basic climate pledge. But the target won’t afford Australia much cover in Glasgow.

This nation still doesn’t have a 2030 emissions-reduction target that passes international muster. It does not have policies to achieve more near-term emissions reductions or a strategy to transition economically and socially.

The paucity of process around Australia’s climate policy must end. We need a proper long-term emissions strategy – one that’s transparent, inclusive and informed by the best available knowledge.

EPA

Does the net zero target really matter?

Nearly all industrialized countries and developed countries have declared net-zero goals or pledges. This includes China, Russia, and Saudia Arabia.

Cynically, it can be thought that targets for the middle part of the century are a way to get the ball rolling. But they’re important signposts – an affirmation of commitment to the long-term goals of the Paris Agreement.

Importantly, a long-term commitment requires action in the interim.

Future policy-making will be more influential if net-zero targets are used. They are important for investment decisions.

The net-zero goal in Australia could also serve another purpose. The fact it was adopted by a conservative government previously opposed to substantial climate action could help end the political “climate wars” which have raged in Australia since 2009.

Net-zero will likely be a durable bipartisan cornerstone – giving the political contest a chance to move beyond whether to do it, to how to do it.

Continue reading:

Reaching net zero is every minister’s problem. Here’s how they can make better decisions

Shutterstock

What about the 2030 target.

However, Glasgow will largely take mid-century net zero targets as a given. High-level political talks will be focused on stronger emissions targets for 2030 – and almost all developed countries have 2030 targets far more ambitious than Australia’s.

Based on 2005 levels of emissions, Australia will seek to reduce its emissions by 26-28% by 2030. The United States has also committed to a significant reduction in emissions. 50-52% reductionDuring the same time period.

Other important points of reference include the United KingdomAnd European Union, which respectively target emissions reductions of 68% & 55% on 1990 levels. JapanBased on 2013 levels, has committed to reduce emissions by 46%

Australia’s 2030 ambition, put forward at the Paris climate talks in 2015, was relatively weak even back then. Six years on, it’s not even in the ballpark of what’s acceptable internationally. Australia will be the only country that has not met its Paris target since Paris.

The majority of the 26% target has been met, mainly through emissions reductions from land-use changes and forestry. This was mostly achieved between 2005 and 2012. In fact, the most recent official figures project Australia’s emissions will decline by 30-38% by 2030, without new policy efforts beyond technology support.

The government’s tactic is to argue that Australia over-achieves on its targets. But the purpose of setting goals is to establish an ambition and then let that ambition drive policy actions.

Others nations will argue that Australia should set a higher target than 38% and not the 26-28% currently being set.

The existing target is not enough to guide the transition to low carbon economies. The Business Council of AustraliaThe government is calling for a reduction in emissions of 46-50% by 2030.

We need a national plan

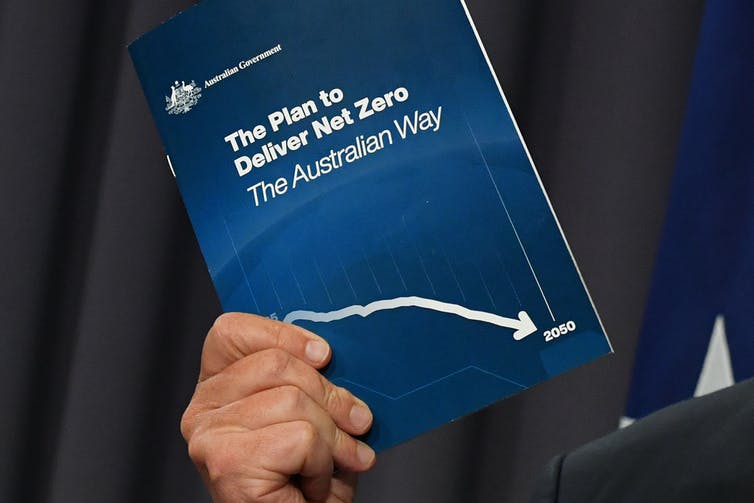

The document accompanying the federal government’s net-zero announcement last week was heavy on politics and light on analysis. The government called it a “plan”, but in reality it was little more than a statement of aspiration.

It assumes that technological innovation will lead Australia to net-zero. However, much of the technology that we need is already available. This includes, but is not limited too, to:

- electricity (renewable energy and energy storage, decentralised power supply)

- transport (electric vehicles, hydrogen in heavy transport)

- Industries (electricity to heat and processes, hydrogen specifically for specific uses)

- Agriculture (lower carbon practices and products).

After many years of very limited climate policy, even a moderate effort in policy could be a welcome change. harvest much low-hanging fruit.

Policies can be tailored to specific applications, including market and regulatory reform, R&D support, and broad-based and specific incentives and regulations. They can also be used to support the economic transition in specific regions and industries.

A carbon price is an important part of a sensible policy combination. Carbon pricing is the. most cost-effectiveMechanism to move to low-emissions production. Australia’s political class must overcome its hang-ups about carbon pricing. Over 20%Global emissions are now subjected to carbon trading or a tax on carbon, and this is a good thing.

Shutterstock

What are the cost?

But there’s no escaping the fact Australia’s fossil fuel industries will bear most of the economic cost of a global shift to net-zero, as demand for fossil fuels declines and eventually dries up. This is out of the government’s hands.

Governments can help, though – not by propping up old industries, but by investing in infrastructure and economic diversification, worker retraining and social programs.

And there’s a huge upside to the transition. Australia’s comparative advantage in renewable energy means such industries could become very large, if we’re smart about it.

A proper national conversation

Quite inexplicably, the modelling underpinning the government’s net-zero plan has not been released. It’s but one small illustration of the paucity of process around climate policy in Australia.

Governments should not be releasing glossy brochures full of political messaging that were created behind closed doors. This is not the right way to deal with a long-term, complex national issue.

AAP

Australia needs a long-term strategy to reduce emissions that clearly maps out how the country will be positioned for success in a low carbon world. It should be openly developed, draw on the best knowledge available and include all stakeholders.

This can lead to a shared understanding between industry, state and federal governments, unions, civil society, and communities. Universities can bring analysis and research to the table.

Many other countries have prepared long-term emissions strategies of this kind, often led by independent statutory agencies like Australia’s Climate Change Authority.

Perhaps our prime minister will be back from Glasgow with some good ideas on how to start a real discussion.

Continue reading:

Australia’s net-zero plan fails to tackle our biggest contribution to climate change: fossil fuel exports

Source link