[ad_1]

As an environmental historian scholar of the 19th century, I spend a lot of time thinking about how the past can help us confront our current crises – especially climate change.

And there’s a lot of help to be found in the 1800s, from the appreciation of wildness in Henry David Thoreau’s famous “Walden,” to the rise of ecology, the science of interdependence. “We may all be netted together,” Charles Darwin scribbled in his notebook.

But my nomination for the most helpful climate manual ever written might be a surprise: “Moby-Dick.”

Herman Melville’s epic novel about life aboard a wayward whaling ship, published 170 years ago this month, does not have a reputation for being particularly pragmatic, unless you’re looking for tips on swabbing the decks or hunting creatures of the deep. And no, I’m not suggesting

We go back to burning sperm oil.

What makes “Moby-Dick” especially relevant right now is that it offers a spur to solidarityperseverance and determination. Those are all qualities societies might need to be able to rely on when we face the overwhelming threat from climate change. Although there is no clear moral to the novel, it does remind readers that even though the water is swirling around them, we can still at least buoy one another up.

Existentialists at Sea

Climate change impacts on time scales that are not human-defined and planet systems that are not easily understood by humans aren’t wired to fathom. But at the same time, it can be seen as just another challenge we’ve brought upon ourselves through societal failings.

Perhaps it’s more helpful, then, to think about climate change not as a brand-new “existential threat,” but as the kind of age-old crisis that is tailor-made for existentialism – a philosophy, as the scholar Walter Kaufmann put it, that is all about “dread, despair, death, and dauntlessness.” The basic idea is to recognize how treacherous and unknowable your path is, and then to continue on anyway.

“Moby-Dick” is clearly an existentialist text, though it was published almost a century before the term was coined. Nobel Prize winner and one of the founders modern existentialism. Albert Camus. acknowledged Melvilleas an intellectual grandfather. And two of the main characters in “Moby-Dick” are near-perfect existentialists: the narrator, Ishmael, and his friend, Queequeg, a harpooner from the fictional isle of Kokovoko.

Ishmael’s obsession with the human condition is evident from the very beginning of his story. He’s bitterly depressed, angry, even suicidal: “it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul,” he says on page one, and he finds himself “pausing before coffin warehouses.” He hates the way modern New Yorkers seem to spend their days “tied to counters, nailed to benches, clinched to desks.” All he can think to do is go to sea.

Of course, it’s not long before he has a near-death experience on the open water. After failing to catch the whale they were looking for, he and a few of his crewmates are forced from their small boat. Queequeg signals with their one faint lantern, “hopelessly holding up hope in the midst of despair.”

Immediately after they’re saved, Ishmael interviews the most experienced of the crew and, confirming that this sort of thing happens all the time, goes below decks to “make a rough draft of my will,” with Queequeg as his witness. The “whole universe” seems like “a vast practical joke” at his expense, but he finds himself able to smile at the absurdity: “Now then, thought I, unconsciously rolling up the sleeves of my frock, here goes for a cool, collected dive at death and destruction.”

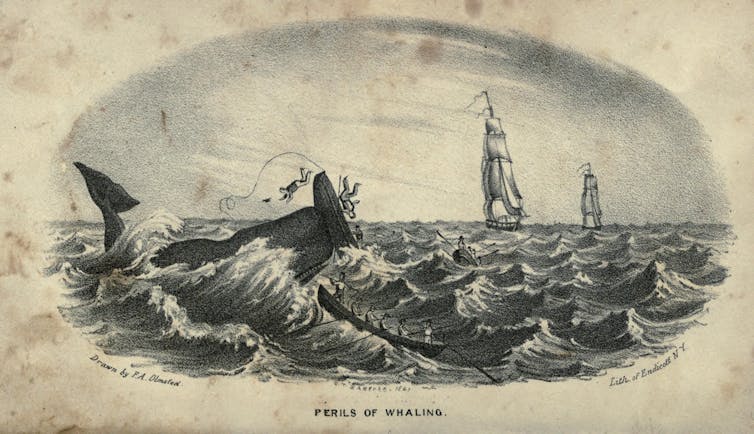

From ‘Incidents of a Whaling Voyage,’ by Francis Allyn Olmsted.

There is no such thing as an island.

Again and again, “Moby-Dick” forces readers to confront despair. But that doesn’t make it a grim read, or a paralyzing one – in part because Melville himself is such an engaging companion, and much of the book imparts a powerful sense of fellowship.

Literary critic Geoffrey Sanborn writes that Melville meant for “Moby-Dick” “to make your mind a more interesting and enjoyable place.”

“It’s about the effort,” Sanborn he writes, “… to feel, in the deepest recesses of your consciousness, at least temporarily unalone.”

When Ishmael stops by the Whaleman’s Chapel before his fateful journey, “each silent worshipper seemed purposely sitting apart from the other, as if each silent grief were insular and incommunicable.” But once aboard his ship, he finds all the crew members suddenly “welded into oneness,” thanks to their shared sense of purpose and their awareness of the dangers ahead. And he sees the same kind of unity in “extensive herds” of sperm whales, as though “numerous nations of them had sworn solemn league and covenant for mutual assistance and protection.”

That’s the sense of interconnectedness human nations need today. When I picked up “Moby-Dick” earlier this month, I almost immediately thought of the climate change negotiations in Glasgow – and Queequeg’s small island home. I could easily see the harpooner being an eloquent representative for a nation that is in danger of being swept up by rising water.

“It’s a mutual, joint-stock world, in all meridians,” Ishmael imagines Queequeg saying at one point in the novel. “We cannibals must help these Christians.” That’s a startling line, emphasizing Melville’s suggestion that Queequeg, whom many characters dismiss as a “heathen,” is actually the most ethical character in the book.

But in Glasgow, it seems, wealthy nations’ recognition of the need for mutual aid fell short. Although their disproportionate greenhouse gas emissions are largely to blame for poorer countries’ disproportionate suffering, their funding for developing nations to weather the storm is far below what’s needed – and eventually, that may come back to bite everyone.

Queequeg’s interdependent relationship with Ishmael is at the very center of “Moby-Dick.” Their fates are interwoven; Queequeg is Ishmael’s “inseparable twin brother.” In one scene, the harpooner dangles over the water, attached by a cord to Ishmael, so that “should poor Queequeg sink to rise no more,” our narrator would go tumbling into the sea as well.

The novel ends with all the whalemen except Ishmael sinking to their deaths. Queequeg’s coffin, which he had made for himself, is what saves the narrator. It was then given to First Mate to replace a lifebuoy that was lost. Much about “Moby-Dick” will always remain murky, but this symbolism is clear: To ponder death and prepare for the worst are age-old survival strategies.

Queequeg’s culture led him to confront the hardest realities of life. As Ishmael notes admiringly, the harpooner had “no civilized hypocrisies and bland deceits,” no tendency toward denial. He had thoroughly enjoyed carving his coffin, and when he lay down in it to check the fit, while suffering from a life-threatening fever, he had shown a perfectly “composed countenance.” “It will do,” he murmured; “it is easy.”

Queequeg’s existentialist determination in the face of dread, his willingness to sacrifice, his caring forethought, made all the difference. Perhaps that can be an inspiration. The key to addressing climate change won’t be some abstract injunction to save the planet; it will be about acknowledging interdependence and commonality and accepting responsibility. It will be about returning Queequeg’s favor.