Private equity will be facing new pressures as interest rates begin to rise from a decades-long decline, hovering around the zero lower bound and possibly increasing significantly. The inflow of capital into the asset class will slow down, which will lead to increased scrutiny of costs and the possibility to shift bargaining power towards limited partners. The first LTI Report states that, while the private equity industry has taken promising steps to innovate and preserve momentum, adverse macroeconomic conditions will likely still prevail, affecting industry growth and, subsequently its cost structure which remains controversial.

Private equity is an exceptional form of long-term capital and plays a significant economic function. It is therefore crucial to understand how developments within the private equity sector interact with macroeconomic trends. Axelson et al. 2013). However, there is an analysis of the industry’s interaction with longer term trends. The secular decline of interest rates coincided with an increase in long-term alternative managers over the past 40 years (Bean 2015). This has been a significant tailwind for the industry’s growth as debt markets became increasingly cheap and institutional investors were looking for ways to offset shrinking yields on fixed-income portfolios. This is the first in a new series of reports from the University of Torino’s Long Term Investors think tank ([email protected]I will be discussing CEPR and ) with you. I’ll also discuss what to expect when this pressure subsides (Ivashina 2022).

DonwloadWhen the Tailwind Ends: The Private Equity Industry and the New Interest Rate EnvironmentHere is the,LTI Report 1.

The changing environment

In 2021, private equity industry fundraising reached a new high. At first glance, it might appear that industry’s dynamic has not been affected by the fact that interest rates have been at their current zero level for over a decade. Contrary to other financial segments, the relationship between private equity asset demand and the interest rate environment are not contemporaneous. This is due to limited access to funds, long-dated holding periods, illiquidity, and constrained access. It is also important to note that investors are not able to exit the alternatives space in a single decision. It takes a lot of time and resources to build the necessary relationships and knowledge.

The history of limited partner capital flow to private equity can be best described as a series of overlapping waves that were initiated by a few significant strategic shifts in allocations made by institutional investors. Each wave took over a decade for each to unravel.1The new wave was initiated in response to the near zero rate environment that surrounded global Financial Crisis (GFC), and recovery period. This led to significant structural changes in the allocation of alternative investments for pension funds and other investors. This is the shift that has fueled the fundraising success of recent years.

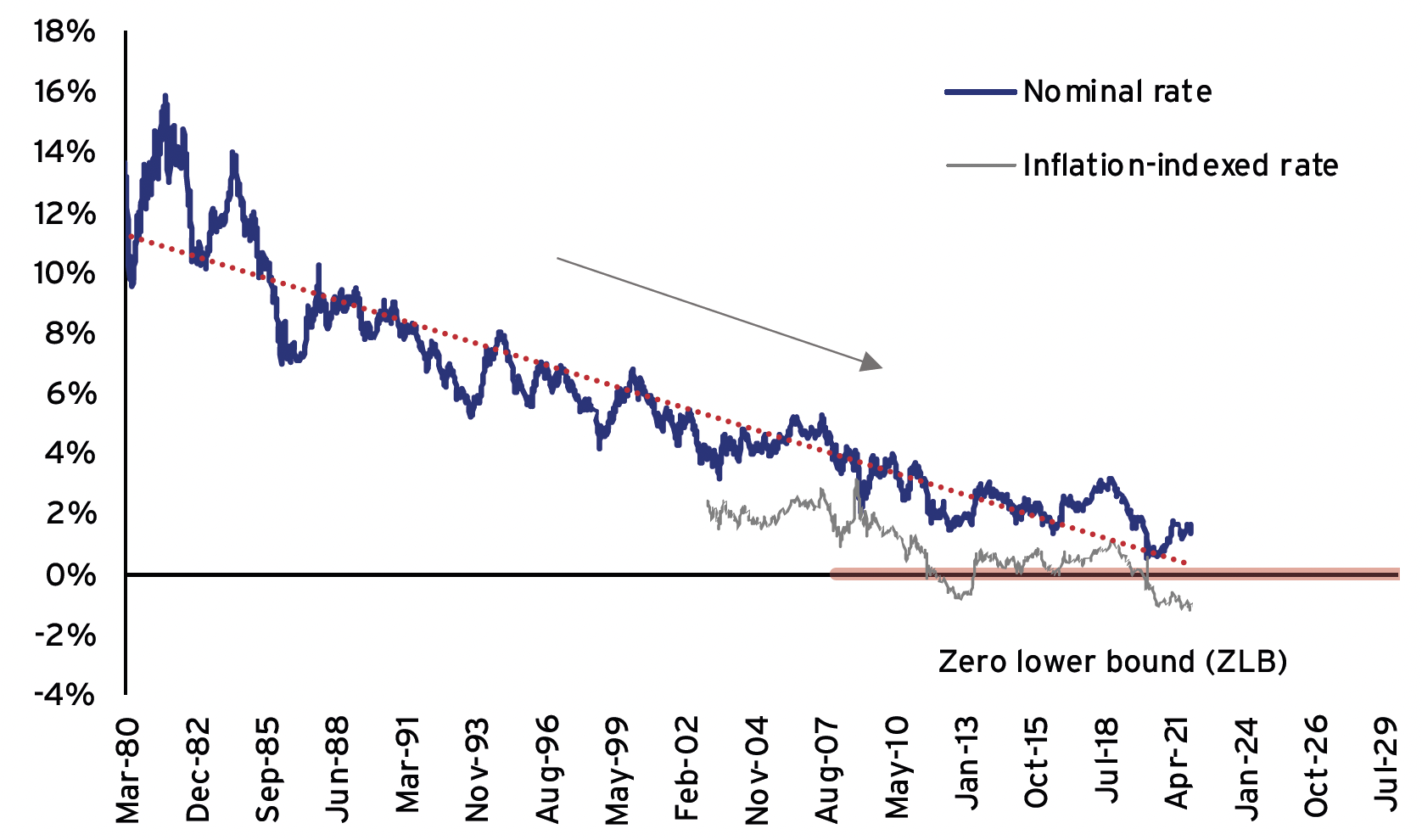

Figure 1Ten-year US Treasury constant maturity rate, 1980-2021

Source: Compiled from https://fred.stlouisfed.org.

Although it is unclear when the interest rate rise will occur, it is clear that the nominal rates will either remain close to their zero lower bound or increase (see Figure).2Private equity would be most vulnerable to a significant rate increase. This would likely lead to limited partners reducing their allocations for private equity and making more selective use of funds. This could have many implications.

- First, due to the inliquidity and long-term nature private equity assets, significant dispersion among returns, as well as bilateral or relationship-driven fundraising, creates scarcity of access to individual funds. Private equity funds have the bargaining power when it comes time to split the returns. As the industry’s growth slows, the pendulum will shift to fewer partners, but longer-term than what we saw in the GFC.

- We will also be able to see a greater scrutiny of the industry’s cost structure and value-add. It is a costly asset class with low net returns and limited partners that fail to beat public benchmarks (e.g. Harris et al. 2014).3Large funds management fees are a major problem. They typically range from 1.5% to 2.2% of the committed capital in the first five year of a fund’s life.4This structure is lucrative for managers, but highlights the disconnect between private equity firms’ income stream and fund performance, especially large funds.

- Third, smaller funds would be particularly vulnerable to such pressures. The strong capital flow and desire to own more of the fund economics, which has led to the proliferation of generalist funds over the past decade, was partly responsible. These funds have a higher-integrated cost structure. Larger funds can therefore have more flexibility in reducing fees and have greater ability to explore the investment space. All of this means that larger-scale firms are more likely to withstand adverse market pressures, which results in market consolidation.

- Finally, there is increasing demand for greater transparency in the industry. Recent legislative proposals have been made to regulate the industry, especially in relation to fee transparency. If there is significant progress in disclosure of fees and expenses, it will likely intensify the negative pressures that result from the new interest rate environment.

If rates are at zero and we continue to have a hockey stick scenario, then the consequences are unlikely to be quite as dire. However, the industry’s incredible growth over the past decade will likely fade. It all begins with the allocation of portfolios by pension funds and other large limited partnerships. This is based on projected performance. Fixed income returns cannot be reduced further and limited partners have already begun to invest in private equity. We expect growth to be equal to the growth in assets of limited partners. This would mean that the industry’s risk-return profile as well as its cost structure will be in the spotlight. The only thing that is different is the time frame in which these pressures could occur.

Innovating the industry

The new interest rate environment will put pressure on the industry’s ability to innovate to maintain momentum. The most exciting trend, and one that expands the frontiers of private equity investment options, is the increasing lengthening of the investment (holding period). A significant industry transformation would be the movement towards a seven or ten year holding period for individual deals. Private equity is often associated with long-term capital and patient capital. However, the industry is almost entirely focused upon the five-year holding period. This means that it takes five years to exit. That means that growth and/or turnaround results must be evident in four years. It is easy to see how the opportunities and needs of sophisticated active management are greater than those initiatives that can produce results in four year.

This trend could take off on a large scale. This trend is unlikely to take off quickly. The problem is the lack of information and, in turn, the weak governance that comes along with illiquidity. Mandatory exits give a clear view into the performance of a fund. The misalignment between limited and general partners can increase if the holding period is longer. Different compensation for investment professionals is a good idea. First, it creates a problem because carry, already removed far into future, is being pushed further. Second, it doesn’t solve the problem with gambling for resurrection or just shirking (while charging an fee) when things don’t go as planned. The extension of the investment time horizon is the trend that has the greatest growth potential, but it is unlikely it will be the new normal.

The second important trend that could offset the pressures from a diminishing macroeconomic tailwind, is the growth of the investor pool. It’s simple: If capital flow from one client slows down, add another. The problem is that retail is still a untapped market. In the past, fundraising was expensive and time-consuming even for large cheques. It is unclear how the industry can fully decentralize fundraising while avoiding major regulatory increases. The entry of US defined-contribution pension plans to the private asset group is a significant step in this direction.

Conclusions

Because of the unique nature of private equity assets, its growth follows an unmatched trajectory. This trajectory is difficult to understand if we don’t consider the long-term, overlapping cycles. As it stands today, the industry is facing persistent adverse macroeconomic conditions. Although there are some interesting experiments taking place in the sector, none of these benign trends seem to be able to offset the capital push to alternatives. The industry’s existence is not in question, but its growth and, with it, its sustainability. This is an opportunity for limited partners to negotiate rent splits between private equity firms, their investors, and the resilience and high fees, despite the growth in fund size and compression of returns.

However, this should not be taken as a given. The slow capital inflow will likely have a disproportionate impact on smaller and younger funds. Larger funds will likely continue to receive significant fund inflows, especially as the industry consolidates. We might see smaller private equity firms leave the market, but the cost structure of large firms will not change if there isn’t an informed approach or coordination among limited partners. It will take proactive coordination efforts by limited partners to reach a new cost structure that is more aligned with private equity incentives.

Refer to

Axelson (U, T Jenkinson), P Stromberg and M Weisbach (2013). Borrow cheap, buy high? The Determinants and Pricing of Buyouts. Journal of Finance 68(6): 22232226.

Bean, C (2015). Causes & consequences of persistently low rates of interest, VoxEU.org 23 October.

Harris, R S., T Jenkinson S N Kaplan, and R Stucke (2014) Is Private Equity Persistent? Evidence from Venture Capital Funds and Buyouts, Darden Business School Working Paper No. 2304808.

Ivashina V (2022). The Tailwind is Over: The Private Equity Market and the New Interest Rate EnvironmentLTI Report 1, [email protected]CEPR.

V. Ivashina (2019), Patient Capital: The Promises and Challenges of Long-Term InvestmentPrinceton University Press.

Endnotes

1 Frictions in making such strategic decisions for limited partners (discussed Ivashina & Lerner 2019) further delay and stretch industry’s response to shifts.

2Pension funds (essentially), target real rates. Current expectations of inflation in the US and EU beyond 2022 is close to its historical target.

3 This does not mean that not all private equity funds have been successful in generating consistent returns. These are easy to spot as they are often rewarded with high capital flows.

4. After the investment period (usually five years), the fee base shifts to the remaining capital and gradually decreases to 1%.