[ad_1]

Niels Thygesen, Roel Beetsma, Massimo Bordignon, Xavier Debrun, Mateusz Szczurek, Martin Larch, Matthias Busse, Mateja Gabrijelcic, Laszlo Jankovics, Janis Malzubris 16 March 2022

The fourth annual EFB conference1 focused on the linkages between public finances (both in terms of sustainability and quality) and the policies aimed at mitigating climate change. The Paris Agreement and European Green Deal have set ambitious carbon reduction targets by EU member states to make the Union the first major economy to be climate-neutral by 2050. This tectonic shift (Weder di Mauro 2020) will require EU governments to make bold and difficult decisions, which could have significant consequences for economic growth and the public finances.

Valdis Dombrovskis was the Executive-Vice President at the European Commission. He opened the discussion by asking how governments can achieve growth-friendly public finances given the threat posed by climate change for fiscal sustainable. Their implications for fiscal sustainability are not as well understood as the financial stability impacts of climate change. The EFB conference was held to fill this gap. It aimed to clarify the challenges posed in climate change for the conduct and sustainability of fiscal policy and, thereby, the future of EU fiscal framework.

Understanding the climate risk to government bonds

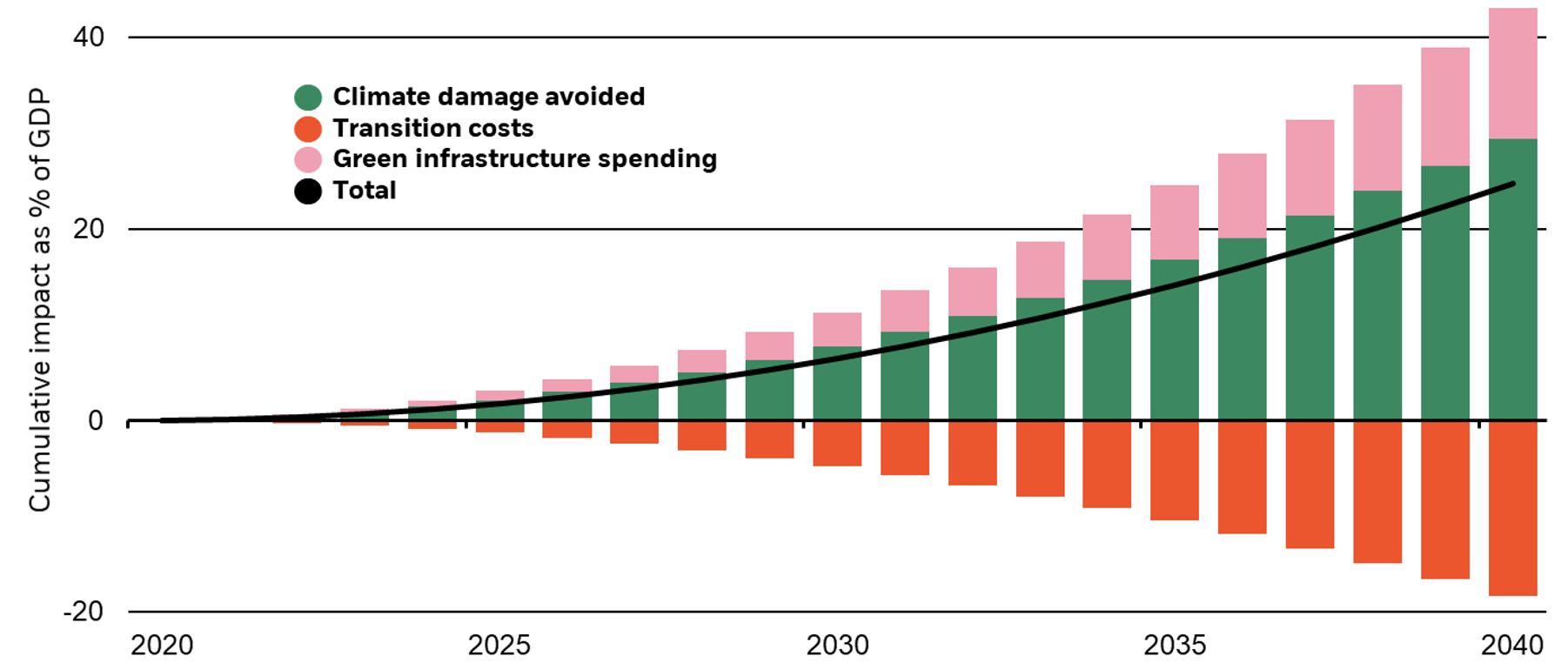

The government can use a wide variety of tools to support the transition to a low-carbon economy. In his keynote speech, Frans Timmermans (Executive-Vice President, European Commission) stated that carbon neutrality requires a combination of investment and carbon pricing emissions trading system (ETS). These changes will undoubtedly have important macroeconomic and structural budgetary implications. Despite the substantial costs of mitigation policies, Isabelle Mateos y Lagos of BlackRock argued they are not sufficient to cover the estimated damage under a business as usual scenario (25% of 2019 global gross domestic product). Figure 1 shows that climate policies would have a positive net welfare impact.

Figure 1 Transition results in net economic gains (estimated cumulative GDP effect of transition, 2020-40).

Notes: The bars indicate the total estimated impact of three factors. They are: avoided damage from climate changes due to mitigating policy (positive), green spending on infrastructure (positive) as well as costs associated with the change (negative). The black line represents the estimated net impact.

Source: Isabelle Mateos y Lagos: BlackRock Investment Institute, Banque de France, International Energy Agency, OECD.

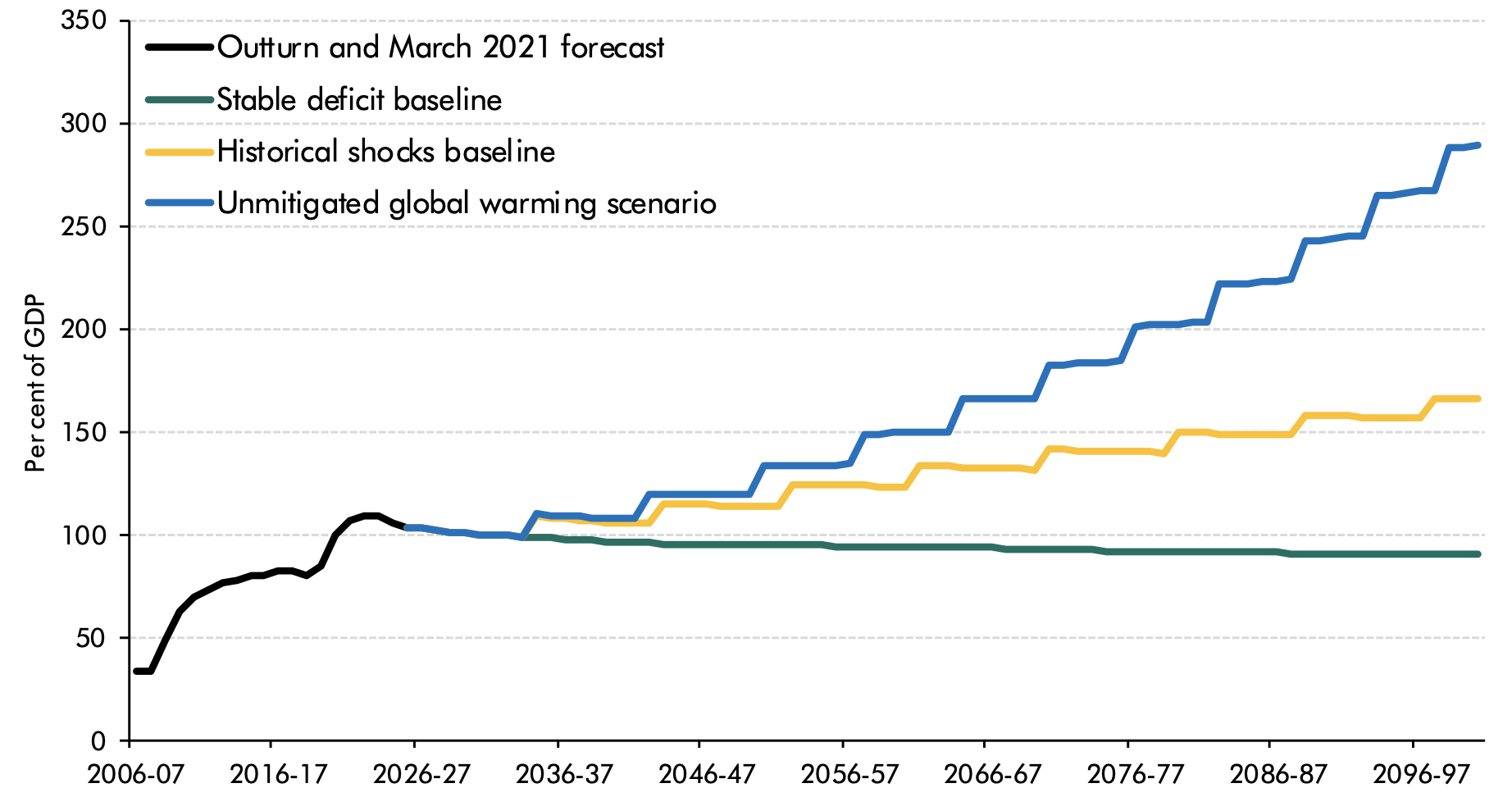

Inna Oliinyk (Network of EU Independent Fiscal Institutions), a specialist in the study of the financial consequences of unmitigated global climate change, confirmed that the budgetary impact of inaction would be far worse than the decarbonisation costs. A case study from the UK shows that public sector debt would be twice higher if there were no mitigation policies, and it would take 80 years to pay off. Rick van der Ploeg (University of Oxford), also demonstrated that delayed mitigation policies only inflated future spending on adaptation measures, eventually leading to higher income taxes.

Figure 2 Three scenarios for long-term public debt developments

Source: Office of Budget Responsibility (2021).

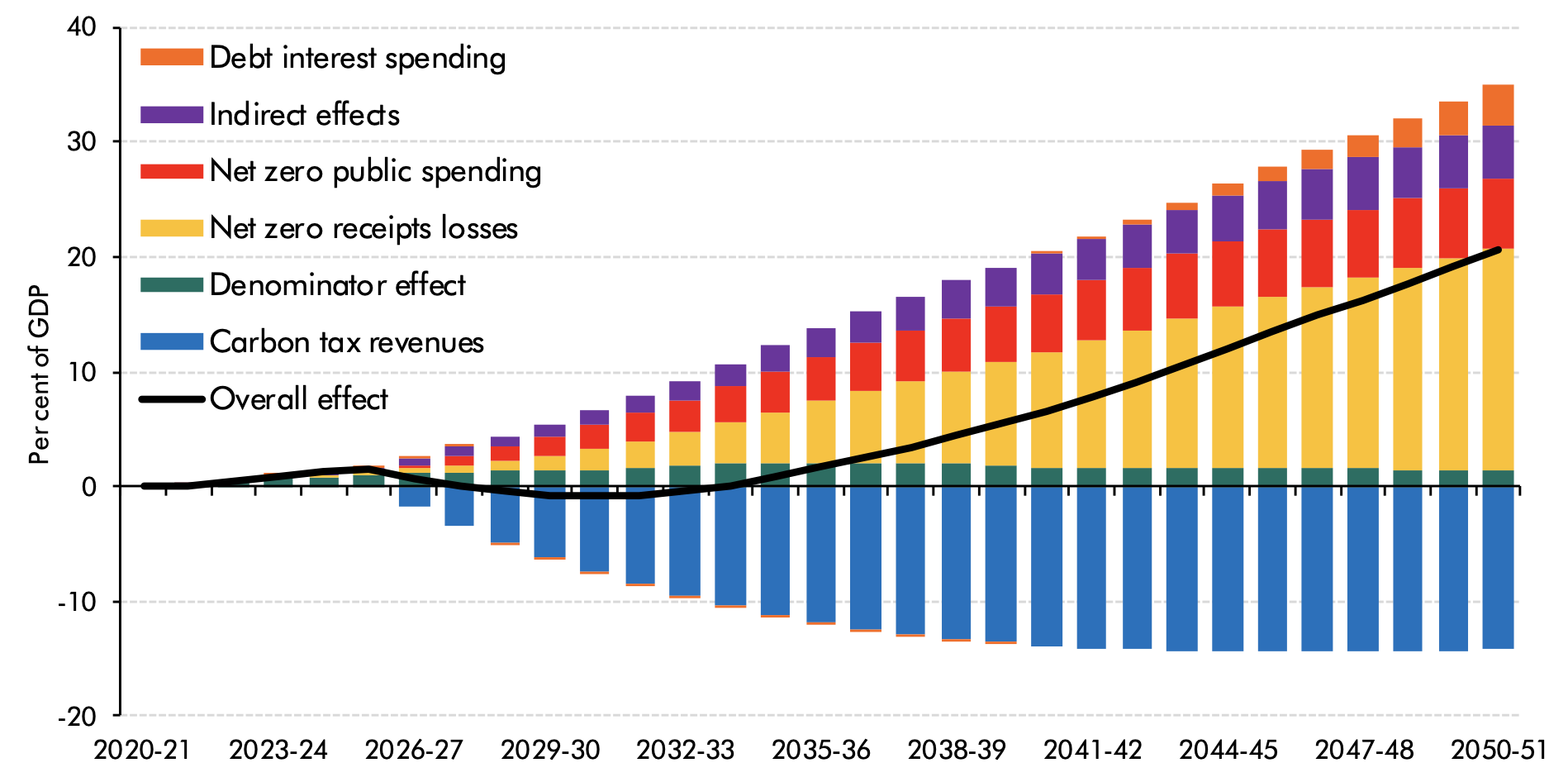

Green taxes aim to increase the shadow price carbon. They can reduce emissions and provide fiscal space for growth-friendly policies such as tax cuts and distortionary tax cuts. However, the double dividend concept is misleading. In fact, Pigouvian taxes that are well-designed are designed to destroy their own tax base. In the long run, revenues from green taxes are bound to disappear. The bottom line is, higher revenues cannot offset the costs of mitigation measures, which results in higher public debt (Figure 3. A coordinated approach at EU-level might be helpful in designing efficient and effective mitigation policies.

Figure 3Net debt impact upon reaching net zero in 2050

Source: Office of Budget Responsibility (2021).

Implementing mitigation policies presents fiscal challenges

It is expensive to address climate change and mitigate its effects. Due to the post-Covid legacy with historically high public debts, governments will have to make difficult choices in order to maintain debt sustainability. According to the European Commission, Europe will need around €520 billion in additional investment per year over ten years to achieve its climate targets. Under the 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) and NextGenerationEU (NGEU), the EU has secured around €86 billion per year in public funding. Even though public investment must be increased, the majority of the investment required will have to come from private sources.

Guntram Wolff, (Bruegel), argued technology and innovation are key to achieving climate goals. Based on past experience, he was skeptical about whether politicians, faced with the need consolidate public finances, would be willing pay for additional investment through cutting current expenditure. This argument was consistent with the work of Larch et al. (2022), which shows that in the aftermath of crises, policy makers tend not to boost public investments.

As if prioritisation wasn’t difficult enough, Rick van der Ploeg from the University of Oxford argued that it was fraught in political frictions. The following five main obstacles are evident from experience in the efficient greening our economies: (i.e. carbon taxes are much higher than fossil fuel subsidies,(ii. carbon taxes hurt the poor disproportionately), (iii. free riding behaviours exist everywhere on the international stage,(iv.) the burden to pay for mitigation is unevenly divided over generations, (v.) electoral considerations tend towards favouring easy solutions such a preference for taxation over subsidies. Van der Ploeg advocated for greater attention to distributive considerations. He supports the channelling of tax revenues to poorer people, organising transfers between rich and poor countries, and future generations to current citizens (through debt). Xavier Debrun, EFB, argued that the green program magnified the deficit bias which is often a result of political frictions. In particular, governments prefer a package policy of mitigation policies that favor subsidies (over taxation), public investment (over targeted tax and regulatory measures encouraging private investment), and a combination of both. In an environment where interest rate rises are likely to continue, the green agenda provides a pretext for higher deficits. Since debt is not taxable, returns look high.

It is important to assess the impacts of climate change upon public finances in a better way

A first step to addressing political biases is to ensure that all those involved in the budget process understand the effects of climate change. Unfortunately, many countries do not have a complete assessment of the effects of climate change on fiscal sustainability. Inna Oliinyk says that only a third of national governments have done such a thorough analysis. Helene Rey (London Business School), stated that authorities don’t have the incentive to act right away if there are no future liabilities due to climate changes. She suggested enriching the standard debt sustainability analysis with such estimates.

Comprehensive assessments could, in principle, benefit from the input or at most vetting of independent bodies like national independent fiscal institutions (IFIs). The OECD and the EU Network of IFIs noted that not all IFIs are mandated to monitor green budgeting, and that most do not have the expertise or resources to do so. Moreover, IFIs also lack information about governments’ plans, measures and working assumptions. The EFB (2021) says that while IFIs in national countries are now an integral part the EU fiscal framework, their heterogeneity makes it difficult for them to influence the conduct fiscal policy through advice.

Although models for assessing the effect of climate change on fiscal sustainability are still in development, they can be used to provide plausible estimates of climate-related fiscal hazards. Stavros Zenios (University of Cyprus), demonstrated how to link a full-fledged model of assessment to standard debt sustainability analysis. Zenios demonstrates that climate risks can have a significant impact on debt dynamics by incorporating multiple channels through the financial system. It is crucial that governments have a holistic view of fiscal planning.

The future of the EU’s fiscal framework

What does this all mean for the economic governance review, which was relaunched on 19 Oct 2021?1 The current framework being blind to climate change considerations, a natural question is whether these should be added to the list of well-known weaknesses that the reform should seek to address (e.g. European Fiscal Board 2019, 221.

Clear guidance should be provided on how to implement fiscal rules and design for countries in order to create optimal green policies. In his opening speech, Commissioner Dombrovskis stated in no way that the Commission envisages any changes to the Treaty’s 3% and 60% GDP reference values. Instead, the pace of reducing debt should slow and be growth friendly to allow for investment scaling up.

The EU fiscal framework should not be interpreted as limiting the ability to respond to current fiscal challenges in a fiscally effective manner. It should encourage climate mitigation policies without jeopardizing fiscal sustainability. In his closing speech, Commission Gentiloni highlighted two ways to include climate change in the EU’s fiscal framework: either through a green golden rules or a common EU facility. Xavier Debrun (EFB), warned that incorporating green contingencies in rules would make them more complicated, less transparent and easier to circumvent. The Green Deal, a European project that addresses a global problem and green investment, is a natural candidate for being a European public good, funded by a temporary EU fiscal instrument.

The EFB had proposed earlier that the EU budget be supplemented by dedicated national envelopes to provide EU common goods. These include green public investment and transnational infrastructural projects. This facility could be used to protect against cuts in national public investment and would be more efficient than a complex and weak green golden rule (European Fiscal Board, 2021).

Refer to

Network of EU IFIs (2021), “Assessing the fiscal policy impact of climate transition”, February.

European Fiscal Board (2019), “Assessment of EU fiscal rules with a focus on the six and two-pack legislation”, Brussels.

European Fiscal Board (2021). Annual Report 2021, Brussels.

Larch, M, P Claeys and W van der Wielen (2022), “Scarring effects of major economic downturn: the role of fiscal policy and government investment”.

Office for Budget Responsibility (2021), Fiscal Risk Report July.

Thygesen, N, R Beetsma, M Bordignon, X Debrun, M Szczurek, M Larch, M Busse, M Gabrijelcic, E Orseau and S Santacroce (2020), “Reforming the EU’s fiscal framework: It is now.”, VoxEU.org, 26 October.

Weder di Mauro, B (2021), Climate Change: A CEPR CollectionCEPR Press.

Endnotes

2 https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_5321