[ad_1]

Antarctic summer temperatures reach high enough to melt snow and other ice on the surfaces of the great glaciers that make up the Antarctic. around 99%Antarctica. This melting water forms thousands of lakes around the continent’s edges. These lakes are formed on huge platforms of floating ice known as Ice shelvesThese extend from the continent into water.

Sometimes, these ice shelves can be damaged by lakes that form on their surface. Break up. The most famous example of this is the collapse Larsen BAntarctic Peninsula’s ice shelf was shattered completely in a matter weeks. 2002.

Satellites recorded the appearance of and drainage of Many lakes on Larsen B’s surface before it broke up. Scientists believe that meltwater from these lakes caused cracks and crevasses to widen and deepen within the shelf, a process known as hydrofracturing.

The ice shelves act as doorstops and support large masses of ice, known as glaciers, that lie further inland. Hydrofracturing causes them to melt, and these rivers of ice that flow into the ice shelf flow more quickly into the ocean, which contributes to the problem. Rising sea levels.

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Scientists have discovered recently that lakes are extremely valuable. More informationThere are more people living around the Antarctic ice sheets than we thought. Endurance swimmer Lewis PughIn 2020, one kilometre of water was swum through these lakes to raise awareness about climate change. But how does the amount of meltwater in these lakes change over the years and how is that linked to climate conditions. This is what my colleagues and me have looked into in a new study that was published in Nature Communications.

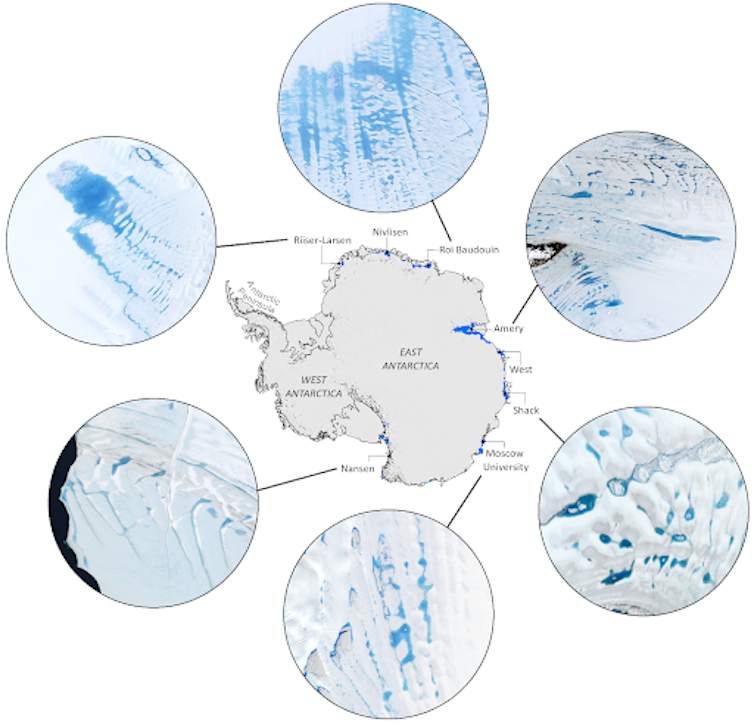

Our research shows for the first-time how meltwater lake volumes and coverage vary over time around the Antarctic ice sheets. We analysed over 2,000 satellite images of the East Antarctic sheet – the world’s largest – to record the changing size and volume of these lakes over the past seven years.

It was difficult to determine whether some ice shelves are at risk of melting under climate change.

Jennifer Arthur, Author provided

We found that the total lake volume varied between years by as much 200% on some ice shelf shelves and up to 72% across all ice sheets, with large differences among ice shelves. The total meltwater in lakes in the entire icesheet peaked in 2017. This water could have filled 930,000 Olympic swimming pool.

More lakes means more warming

Melting at the surface of the sheet doesn’t just form lakes: the water also seeps into air spaces in the layers beneath the surface, where it freezes as temperatures get colder. These layers, known as firn, are made from old snow that has not been compressed into an ice.

If there is more snowfall than melting, the firn will become filled with refrozen meltwater. When this happens, meltwater from the next summer will collect on the surface and form lakes. The more surface melting, the more firn becomes saturated like a sponge, and the more lakes that form on the surface, the greater the risk of fracturing.

We ran simulations of the firn air, surface melt, and runoff on Antarctic Ice shelves to investigate how lake variability changes over time. We found that the volume and area of meltwater lakes can be affected by both summer air temperatures and the air content in the firn. We’ve noticed on satellite images that on some ice shelves lake coverage is already expanding into regions vulnerable to fracturing.

Sue Cook, UTAS, Author provided

Interestingly, we found large differences between where we’ve observed lakes in satellite images and the amount of meltwater that can form lakes predicted by our models. This shows that local climate conditions are more important in predicting surface melt and lake formation than we thought. To better predict Antarctica’s future surface meltwater, our climate models need to be refined.

In a warming worldThese lakes are likely to continue spreading onto ice shelves that could be easily broken up. Our research has made it possible to understand not only where lakes are now forming across the entire Antarctica ice sheet, but also what influences how they change each and every year. This is key to predicting which ice shelves are most at risk of collapse, as well as for improving model projections of Antarctica’s contribution to sea-level rise.