[ad_1]

Southeast Asia’sLargest freshwater lakeIs facing an EmergenciesThe delicate ecosystemis damaged due to a combination climate crisis and drought. Overfishingand upstream dams.

Many of the Tonle Sap lake’s surrounding CommunitiesDepending on the waterSource of their income. According to the Mekong River Commissioner, however, the lake’s volume has fallen below its historical average.

The Mekong River reverses its flow each year to replenish the water supply and feed a large part of the country.

The shorter wet seasons have caused water levels to drop on the Mekong River. This has made many families poorer and unable purchase drinking water, forcing them into dependence on the already diminishing lake.

It also means that the combination of increased Many families have fallen prey to droughts, pollution, and depleting stocks of fish..

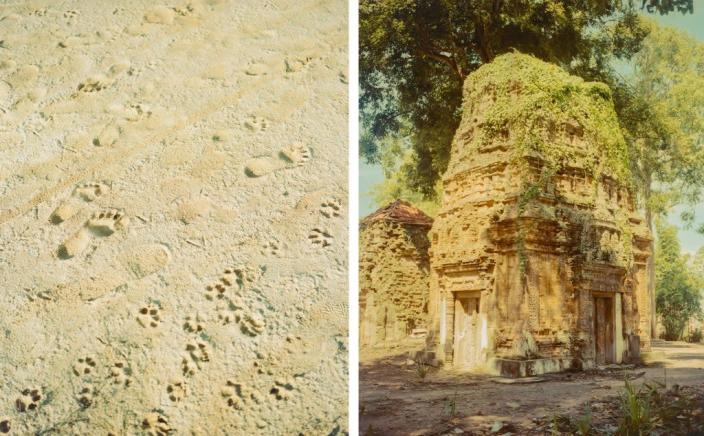

Singaporean photographer Calvin Chow spent 16 days travelling on a “tiny boat” with a translator through some of the 170 lake communities to photograph the ongoing ecological uncertainty.

He has titled this project Once Beating Heart to reflect the delicate ecosystem with relies on the “pulse” of water from the Mekong River to the Tonle Sap lake.

Calvin met Mr Ta when he was photographing the series at the peak of wet season. He lives in an apartment floating with his daughter, three years old. He is unable to pay for clean drinking water because he doesn’t have a regular income from fishing.

Meanwhile, other families are unable to afford decent toilet facilities, with many telling Calvin that installing a permanent latrine is “inconceivable”.

“These families’ lives are shrouded by a complex web of circumstances,” says Chow. “I feel that the Tonle Sap is now at a pivotal point, Climate ChangeThis is seriously affecting those who depend upon the lake. Ultimately it really all boils down to the fact that when there’s less fish, there’s less income for people to afford basic necessities – like water to drink.”

Calvin partnered with WaterAid in this project, hoping that his photographs would tell the stories and inspire people to act.

WaterAid states that it is working in CambodiaCommunities must have access to sanitation and hygiene as well as water that is reliable and can withstand floods, droughts, and other natural disasters. Clean water, decent toilets, hygiene, and sanitation allow people to stay healthy, go school, and earn a living.

“This partnership has given us a platform to showcase new voices telling powerful stories about the impact climate change is having on people’s access to clean water,” WaterAid’s Sophiep Chat says.

“Calvin’s captivating photo series, opening and closing with images of nets, instils a feeling of interconnectedness but hints at entrapment too. Life on the Tonle Sap is both extremely complex and entirely simple, but everyone depends on the water.”

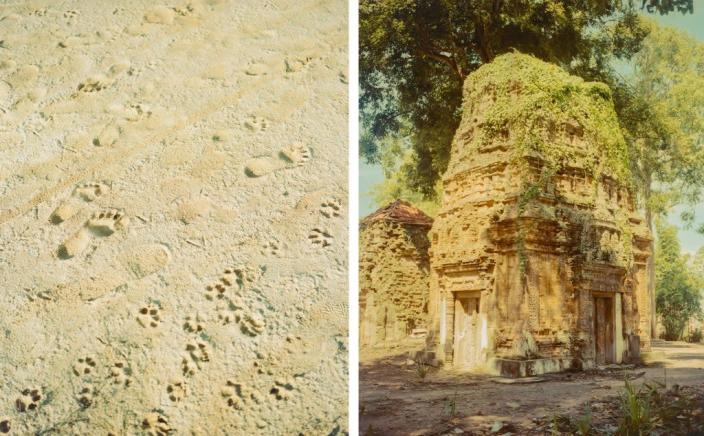

Calvin captures fishing nets suspended from dead trees, and fishermen praying along the lake’s shores to get a good catch. Calvin also photographs the desperate state of the situation.

For inhabitants of the many Tonle Sap’s floating homes, such as Mr and Mrs Paen, falling unwell with water-borne diseases due to unclean drinking water is something of a normality.

These floating homes are often only a few feet above water, which can lead to decreased sanitation and hygiene.

The delicate BalanceBetween man and environment reflected in Calvin’s photographs portrays how sensitive the Tonle Sap lake’s society is to drastic climate change, and how desperately helpless they are in stopping it.

Calvin Chow’s Once Beating Heart was commissioned by WaterAidand 1854/British Journal of Photography