[ad_1]

Climate activists had a mixed year in 2014. There were severe weather events that highlighted our planet’s dangers from a rapidly warming planet. The potential for a cleaner future was shown by the clear skies and blue skies that were created by lockdowns. Ambitious plans bookending failed promises. In keeping with current times, some people continue to believe that humans are destroying the Earth, while others dismiss these beliefs as conspiracy rhetoric.

Indians have both reason to be hopeful and afraid from the perspective of a country with projected emissions that will double or triple in the next 30 years. Our rapid urbanization could provide an opportunity for us as a country to experiment with green, technologically-advanced cities. Our rapid population growth could also allow us to create an economic model of development that does not compromise our environment. India has argued rightly that, as a developing economy responsible for far fewer carbon emissions per capita that our Western friends, we should be granted some, if any, leeway that industrialised nations have had in the past.

While this argument is compelling, it comes at a steep cost. This year, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published a report stating that humans have “unequivocally” caused the climate crisis and that “widespread and rapid changes” have already occurred, some irreversibly. UN Secretary General, António Guterres described the report as “a code red for humanity”. His sentiments seem to be not hyperbolic when we look back on the events of the past one year.

Floods and fire

Anjali Jaiswal, a senior director at the Natural Resources Defense Council, (NRDC), spoke with indianexpress.com, “the climate crisis is hitting us in the face” and the vulnerable continue to suffer the most. Director of Climate Action Network for South Asia Sanjay Vashist stated that there used to be only natural disasters. Now, there are mostly manmade disasters.

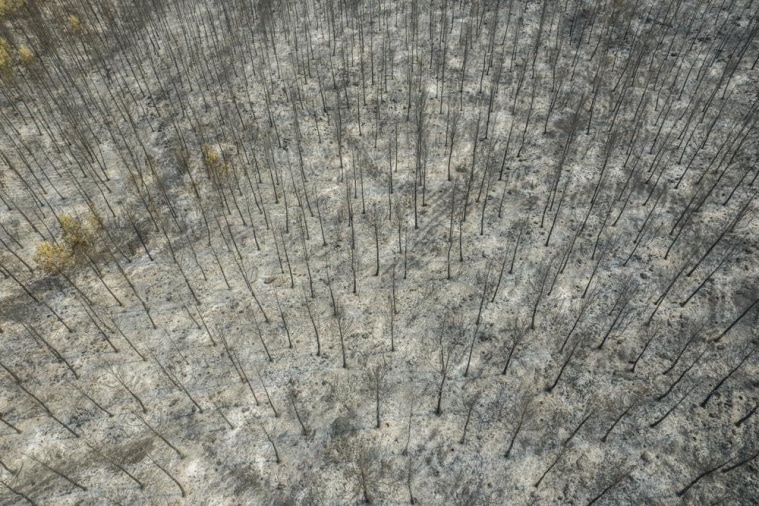

A forest of dead trees is found near the Kemerkoy Power Plant (a coal-fueled powerplant in Milas, Mugla, Turkey (AP).

A forest of dead trees is found near the Kemerkoy Power Plant (a coal-fueled powerplant in Milas, Mugla, Turkey (AP).

In 2021, Greece and the Western United States faced crippling forest fires which burned almost three million acres of land and displaced thousands of people from their homes. In California, which is particularly vulnerable to climate shocks, the drought levels were more extreme than at any point in the state’s 126-year record.In opposite circumstances, in Tennessee, staggering amounts of rainfall led to flash flooding that killed more than two dozen people. Buzzfeed reported that one Buzzfeed article said so. investigationDuring a February deep freeze in Texas, 500 to 1,000 people were killed. Scientists say that those events would be “virtually impossible” without human caused climate change.

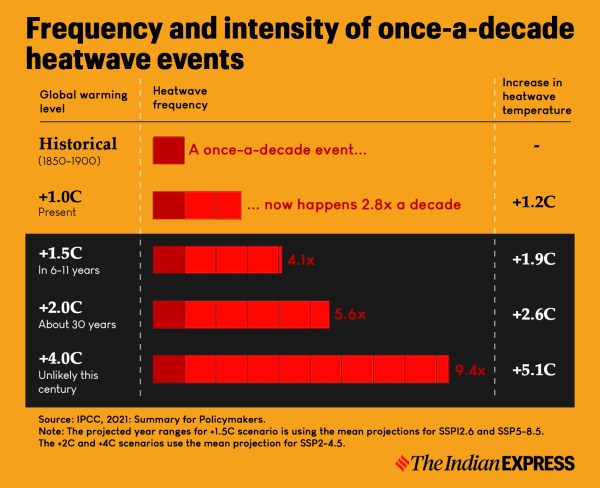

A drought was also experienced in Kenya, Turkey, Serbia, severe rains, flooding in China, and deadly storms in Germany, Belgium, and Turkey. An entire Canadian town was destroyed by a wildfire caused by extreme heat. India’s rainfall caused havoc in Mumbai and the Yamuna River, Delhi, was covered in foam from people dumping heavy sewage and other industrial waste into it. According to the IPCC report events like this, which used to occur around once a decade, now occur 70% more often.

There is no margin of error. Experts warn that we are currently on track to raise the earth’s temperature by 2.4C on average since the pre-industrial era. The last time the world was hotter was 125,000 years back. The world has warmed by an average of 1.2C per year. At 1.5C, countries such as the Maldives will disappear. The Middle East and large parts of India, China, could become uninhabitable beyond 1.5C. Heatwaves will be commonplace at 2C and North America and Europe will have to deal with frequent wildfires. According to the World Bank, if we continue along our current trajectory, by 2050, 216 million people will be displaced, a third of the world’s food production will be at risk and $23 trillion will be wiped from the global economy.

2021 Recapped

Before looking at the positives, let’s examine the negatives from the past year.

The first is an increase in fossil fuel production in 2021. Vashist claims that governments were preoccupied by the responsibility of promoting economic recovery after the pandemic, and decided to do this by extracting fossil fuels at an increased rate. Vashis said that this could have environmental and other problems.t because “private companies don’t mine as per the law but instead, as per their convenience”. Fossil fuels are increasing with the amount of energy produced by coal power plants per annum rising from four percent in 2020 to nine percent in 2021. According to the International Energy Agency (IAEA), the global coal demand could reach an all time high by 2022.

Due to a global energy shortage, European gas prices rose 611 percent in the past year. ReportsThe Economist published data that suggests that this increase shows that the world is still not ready to transition to a purely renewable-based economy. Arguments are that while countries have already developed notable renewable projects, they will not be able to stop economies from collapsing if the oil or natural gas runs out. The report warns against rapid reforms and warns of more energy crises. This could potentially mobilize a popular rebellion against climate policies, und undo much of what has been achieved.

Climate change has also been a significant year for Putin. Russia is already one of the largest natural gas exporters worldwide and has managed to keep its Nord stream 2 pipeline going despite liberal opposition. This pipeline would deliver Russian natural gas to German homes. Right now, Russia is the source of 41 per cent of Europe’s gas exports. Bernstien’s research also suggests that the global shortage for LNG capacity could grow from 2% of demand to 14% in 2030. Russia will continue dominating the market unless other nations begin aggressively exporting LNG.This makes large economies vulnerable to the whims, fancies and desires of the Kremlin. Russia is only one example of an authoritarian government that threatens the safety of global energy chains. The same can be said for Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Iran. As democracy backslides, autocracies rise. It is always a concern when autocratic leaders monopolise valuable commodities.

A significant problem is also the loss of biodiversity. The 11 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide that trees absorb is 27% of the amount that agriculture and human industry emit. Oceans absorb another 10 million tonnes of carbon dioxide, which is close behind. The destruction of natural habitats by human activity and overfishing reduces natural climate sinks and increases our vulnerability to climate disasters.

Brazil, the Amazon rainforest (one such climate-sink), saw more than 13,00 km of forest disappear between August 2020 & July 2021. This represents an increase of 22 percent compared to the previous year. According to a Report in Foreign Affairs Magazine, under President Jair Bolsenaro, Brazil is implementing policies that “Risk tipping the region in A spiral of ecological destruction that could result in the release hundreds of billions upon trillions of tons of greenhouse gases. carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, wipe out ten percent of global biodiversity, and destroy a forest system that is essential to regulating the entire region’s rainfall.” Similar destructive policies threaten the climate and it is worth noting that while Brazil signed a pledge to end deforestation by 2030, India refused to do so.

Lastly, 2021 was undoubtedly the year of cryptocurrency. Cambridge University Study published in February claimed that bitcoin mining alone, at the time, possessed a carbon footprint equivalent to Argentina’s. The strain on the environment caused by mining could increase tenfold as more countries and institutions adopt crypto-friendly policies. Although it may not sound like the dire situation described above, it is serious and will only get worse.

Let’s move on to the positives. Vashist claims that one of the most important developments of the year was Biden’s agreement to re-join Paris Climate Agreement. That, along with statements from other top policymakers, indicate that “they have recognised the importance of attaching a climate lens to the development agenda.” India has also made considerable strides in 2021 with PM Narendra ModiRecently, we announced that 500GW of non fossil fuel-generated energy would be achieved. This would greatly reduce our dependence on coal.

In September, Iceland opened the world’s largest carbon sucking machine, Orca, which is designed to remove 4000 tons of CO2 from the atmosphere each year. Shell, the oil company, was required to reduce its emissions by 45 percent by 2030. The figure is a significant change from the 2019 levels. In March, the world’s first floating wind farm was opened off the coast of Scotland and in April, JP Morgan set a goal to finance $2.5 trillion in the next decade to combat climate change. Later, Citigroup and Bank of America made similar pledges. China pledged in September that it would enforce the 2016 Kigali Agreement and immediately stop emitting HFC23, a greenhouse gas 14600 times more powerful than carbon dioxide. It also announced that it would stop funding oversea coal projects, with the cancellation estimated to avert three months’ worth of global greenhouse gas emissions.

With the negatives and positives covered, we can move on to the biggest mixed bag of the year – the COP26 Summit, an annual meeting of world leaders to discuss issues pertaining to our climate.

COP26

Climate activists were eager to see the COP26 summit in Scotland in November. The Glasgow Climate Pact, which was drafted in November, was significant because it acknowledged that fossil fuels must be phased out but not enough to stop the earth’s rapid warming to unsustainable levels.

The pact required a faster phasing out of coal use and the removal of subsidies for fossil energy. Brazil and Indonesia have signed an agreement to end deforestation in 2030. The agreement recognizes that indigenous people are the best equipped to care for the forests they inhabit. Before meeting in 2022, the governments agreed to increase their national plans for reducing carbon emissions over the next decade.

Bhupender Yadav (Indian minister for Environment and Climate Change) attends a plenary session of stocktaking at the COP26 U.N. Climate Summit in Glasgow, Scotland (AP).

Bhupender Yadav (Indian minister for Environment and Climate Change) attends a plenary session of stocktaking at the COP26 U.N. Climate Summit in Glasgow, Scotland (AP).

India was also praised for its leadership in climate change at the summit. Jaiswal states that “India stepped up with bold pledges to cut climate pollution by a billion tons, in large part by meeting 50 percent of its energy requirements with renewable energy by 2030, signaling a strong commitment to a healthier and cleaner future, for the people of India and the world.” Vashist agrees, noting that India has been much closer to meeting it’s “fair share” of obligations, committing, in relative terms, far more than countries like the US and UK. The NRDC also claims that India is close to meeting its Paris Agreement targets, and that this is sending a strong signal to the world that India is committed to decarbonisation.

Many felt that the promises made at COP26 were not enough. They are not binding and commitments made at similar summits in the past have rarely been kept. Secondly, the difference in tons CO2e between the emission cuts built into the agreement and those needed to avoid more than 1.5C is roughly 17-20 Billion tons CO2e per annum. The lack of climate financing also disappointed developing nations. According to one Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), the Glasgow Agreement promises $356 Million in climate financing. Report, “funding levels remain woefully inadequate.”

Recommendations and challenges

Climate financing is essential for developing countries to move into renewable energy sources. According to the UN Environment Program, developing countries would need $300 billion annually by 2030 to combat climate change. This is far less than they are expected to receive. It is equally concerning to see where the funds are being deployed. According to the CFR report, most funding goes towards mitigation efforts and little is spent on adaptation. This is a crucial distinction. The difference is important. Adaptation allows countries prepare for and work towards eliminating climate catastrophes. Mitigation aims to reduce their impact. For example, a pothole in the road could cause a car accident. Adaptation would involve fixing the pothole, while mitigation would mean having a medical kit in case of an emergency. Vashist and others argue that it is a mistake to prioritize mitigation over adaptation. He warns that adaptation must be prioritized or the poorest and most vulnerable nations will be most at risk from climate disasters.

Vashist asserts that countries such as India should balance the needs of communities that are dependent on fossil fuels against the environment’s needs. This goes back to the fair-share argument, which states that people in the global South should not be treated unjustly compared to those in the West.

The situation is dire, but there are solutions to the climate crisis. Climate financing must be a priority. More money should be diverted to adaptation. One Foreign Affairs ArticleNotes that adaptation methods are possible to be hyper localised and inexpensive. It states that “individual communities and cities can take the lead on their own” by implementing small and simple innovations like painting rooftops white to reduce the heat that they absorb. Additionally, it states that adaptation can consist of “maintaining the natural environment – the forests, coral reefs and coastal wetlands that provide just as much protection against disaster as manmade measures do.” However, man made innovations towards decarbonisation also need to be promoted which, according to another Foreign Affairs article, will include investments in electric power, transportation, heating, and agriculture.

To absorb shortages and transition from oil to natural gas to coal, the government will need to rebuild energy markets. This would include long-term subsidies to renewables, investment for battery storage, diversification supply, and long-term subsidies.

Vashist says that the key to this is not to blame fossil fuel suppliers but to convince them to switch to green energy. He also noted that “green energy solutions” must be carefully evaluated. Nuclear energy is a particular example of this. In terms of renewables, he states that “solar and wind are the most promising” with the former especially important.

Jaiswal argues that as we look ahead, “we need more action and less talk, to implement far reaching climate solutions from India as well as the U.S., China, and all major economies.” She goes on to stress that we need “government, business, and civil society to move into action with the urgency of now, otherwise, the climate crisis will snowball into catastrophic and irreparable devastation for the whole planet”.

Further Reading

Imagine a Green New Deal, Andrew Chatzky and Anshu Siripurapu, Council on Foreign Relations

A Foreign Policy to Protect the ClimateJohn Podesta, Todd Stern and Foreign Affairs Magazine

Climate Finance is Critical for Accelerating Global Action. Alice C Hill, Council on Foreign Relations

Building a resilient planet, Kathy Baughman McLeod. Foreign Affairs Magazine

[ad_2]