[ad_1]

In the Paris Agreement, countries committed to seek to limit the increase in temperature to 1.5℃ above pre-industrial levels. However, even if countries fulfilled their current pledges to reduce emissions, we would still see an increase of around 2.7℃. No wonder, nearly two thirds (or more) of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change authors responded to a revised questionnaire. survey conducted by the journal Nature expect the increase to be 3℃ or more.

So how different would the impacts of climate change be at 3℃ compared to 1.5℃?

At the outset, it is important to point out that – even if impacts increased in line with temperature – the impacts at 3℃ warming would be more than twice those at 1.5℃. This is because we already have an increase of around 1℃ above pre-industrial levels, so impacts at 3℃ would be four times as great as at 1.5℃ (an increase from now of 2℃ compared with 0.5℃).

In practice, however impacts do not always increase linearly with increasing temperature. In some cases the increase accelerates as temperature rises, so the impacts at 3℃ may be much more than four times the impacts at 1.5℃. At the most extreme, the climate system may pass some “tipping point” leading to a step change.

Continue reading:

What climate ‘tipping points’ are – and how they could suddenly change our planet

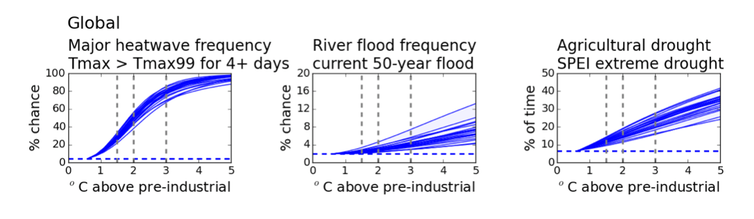

Two years ago, colleagues and me published research that looked at the subject. the impacts of climate change at different levels of global temperature increase. We found that, for example, the global average annual chance of having a major heatwave increases from around 5% over the period 1981-2010 to around 30% at 1.5℃ but 80% at 3℃. The average chance of a river flood currently expected in 2% of years increases to 2.4% at 1.5℃, and doubles to 4% at 3℃. At 1.5℃, the proportion of time in drought nearly doubles, and at 3℃ it more than triples (these are all global averages weighted by the distribution of population or cropland: see the paper for details.

Arnell et al., 2019. Author provided

These figures are subject to uncertainty, as shown in graphs above. The range of possible outcomes grows as the temperature rises. There is also variability throughout the world. This variability increases as temperatures rises, increasing geographical disparities and impact. River flood risk would rise particularly quickly in south AsiaFor example, droughts increase at a faster rate than the global average across the globe. much of Africa.

Dreame Walker / shutterstock

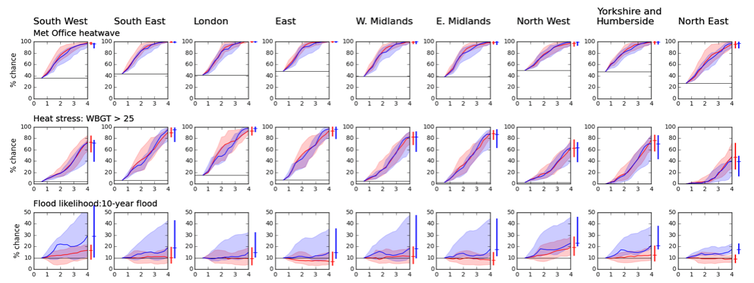

The difference between 1.5℃ and 3℃ can be stark even in places like the UK where the impacts of climate change will be relatively less severe than elsewhere. You can find more information at www.aa.org. recent study, colleagues and I found that in England the average annual likelihood of a heatwave as defined by the Met Office increases from around 40% now to around 65% at 1.5℃ and over 90% at 3℃, and at 3℃ the chance of experiencing at least one day in a year with high heat stress is greater than 50%.

Arnell et al., 2021. Author provided

The global average is increasing at a similar rate as the average time in drought. The chances of what is currently considered a ten-year flood increases in the north west of England from 10% each year now to 12% at 1.5℃ and 16% at 3℃. There is a lot of variability at the UK scale. The risks associated with high temperatures extremes and drought are increasing more in the south and east than in the west. Flooding risks are increasing more in the north and the west. Although there are many uncertainties surrounding these estimates, the general direction and difference between the impacts of different levels of warming are clear.

The graphs in this article illustrate the impact of climate changes in terms of changes in the probability or occurrences of specific weather events. The real consequences for people will depend on how these direct physical impacts – the droughts, the heatwaves, the rising seas – affect livelihoods, health and interactions between elements of the economy.

COVID-19 has shown us that even small perturbations can have major and unexpected knock-on effects. This is also true for climate change. If the relationship between temperature rises and physical impacts such as melting glaciers and extreme weather is often nonlinear, then the relationship of temperature increases with the effects on people and societies is likely to be very non-linear. All this means a 3℃ world will be a lot worse than a 1.5℃ world.

Source link