Divya Anantharaman points her flashlight at the wooden benches that surround an office tower near Wall Street. New York’s streets are still a place for early risers. She says it is crucial to start her weekly search and rescue mission at such an ungodly hour.

She is looking for victims of bird killers: glass skyscrapers. Doormen will sweep the streets clean when daylight breaks and then the evidence of the dead will disappear.

Anantharaman volunteers for NYC AudubonUrban conservation group that monitors bird deaths due to window collisions. She carefully inspects every dark corner of her route, looking through planters to ensure she does not miss any collision victims. She discovers a dead bird underneath a sparkling glass overpass connecting two buildings at her end.

It’s an American woodcock she believes, a migrating bird that is quite common with a long beak. After spending the winter in Alabama and other Gulf states, woodcocks travel through New York every spring. Anantharaman says that the stiff bird indicates that it has recently died. “The eyes are still so clean that it may have happened just minutes ago.” She snaps photos and takes a moment to close her eyelids using her thumb. Then she puts the corpse into her pink backpack.

One billion birds and counting

NYC Audubon estimates that between 90,000 to 230,000 birds are killed each year by New York City buildings. The danger to winged travelers is especially high during the spring and autumn migration seasons, when there are many illuminated buildings in the city.

New York sits along a migration route to South America where many birds spend the winter. Artificial nighttime lighting attracts and disorients birds because they navigate using stars. The birds believe they are flying towards starlight but instead land in an unknown metropolis.

Kaitlyn Parkins, NYC Audubon biologist, explains that reflective glass is the biggest problem. “Birds can’t see a tree in its reflection. It’s a tree to them. They fly at it and can accelerate very quickly, often dying instantly.

Buildings are responsible for the deaths up to a billion birds each year in the United States, according to Daniel Klem, a pioneering ornithologist. Klem calculated this figure in the 1990s. Glass windows are death traps around the world.

“Birds are susceptible to glass where birds and glass are combined.” Klem states that they don’t see the bloody stuff. Klem stresses that it’s not the skyscrapers, but low- and middle-rise buildings that pose the greatest threat.

Klem, who is now a professor at Muhlenberg College, Pennsylvania, sees window collisions as a critical issue in the conservation of birds. He says collision is a threat and should be considered after habitat destruction. “Windows kill in an indiscriminate manner, and that’s what makes them so dangerous. They also take the best of the population. We cannot afford to lose any individual, much less good breeders.

A global problem

Conservation groups and scientists have been taking up the cause in recent years. Binbin Li is the leader of one of two groups that monitor window strikes in China. She is an assistant professor at Duke Kunshan University in environmental sciences and has a Ph.D. from Duke in the USA. She met the leading researcher in the university’s bird collision project.

She says, “First, it was only a problem at Duke. Or in the States, I couldn’t imagine it here in China.” After her return, she received reports about three dead birds on campus in a matter of a month.

She now counts birds that have been killed on campus in Suzhou with a group of students. She notes that many of these victims are found under glass corridors, much like the New York woodcock Divya anantharaman.

Li began a national survey to better understand the problem. Although three major migration routes pass through China, data on fatalities along these routes remains limited. Li said that bird collisions are not well-known in China.

“Just change the glass, and turn off the lights.”

In Costa Rica, Rose Marie Menacho had to convince her professors to let her investigate bird collisions as a PhD student eight years ago. She recalls, “They didn’t know much about it, didn’t know it was an actual problem.” “Even though I was shy about it, I was still studying it. It was too big for me, which made me feel a bit ashamed.

Around 500 volunteers help her understand the scale and importance of the problem in the Tropics. Some keep feathered corpses frozen, while others send her photos and reports. She said, “Not only migrating animals collide.” Her volunteers recovered brightly colored quetzals with flamboyant, large beaks and toucans. Both are local species.

Parkins, NYC Audubon biologist warns that collisions can kill many birds that already have to deal wit climate change, pesticides and habitat loss. It’s simple to fix. Just change the glass and switch off the lights.

Parkins and her team use the data to convince glass building owners to take action. They don’t often need to replace any of the glass. Special foil can make the glass less reflective and help to save energy for heating and cooling. The markings on the windows can help birds to see the structure. Volunteers found 90% less dead birds after a bird-friendly renovation at the Javits Convention Center.

New York City adopted a new law in January which requires that public buildings turn off lights at night during the migration season. For all new buildings, architects must also use bird-friendly design, such as ultraviolet coating on glasses, which is visible only to birds, but not humans.

New regulations are a good place to start

Rob Coover examines a small bird on the sidewalk in front Brookfield Place, a huge office and shopping center at the southern tip Manhattan. He has been searching for dead birds for half an hours, even though daylight is still scarce.

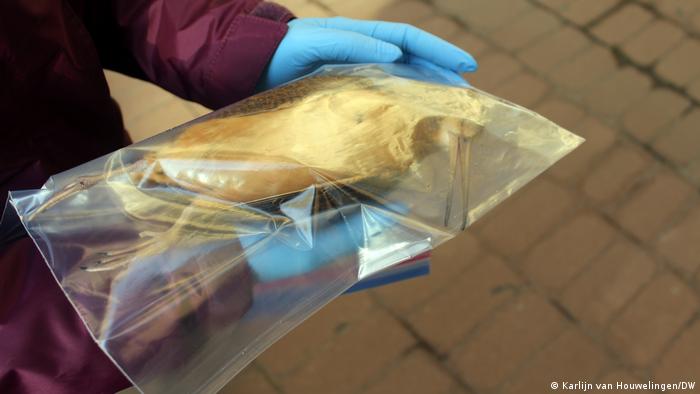

He carefully examines the piles of chairs that workers at a coffee shop will soon use to decorate their terrace. He has already taken photos of a small, stiff corpse twice. To preserve a body, he now uses rubber gloves and sandwich bags from his backpack.

Coover once found 27 birds within a single morning. One of her fellow volunteers made international headlines last September when she found 226 dead birds around One World Trade Center in just one hour.

Coover said, “It is quite depressing all these dead bodies.” Sometimes he finds a surviving animal and takes it to a sanctuary for birds. He usually puts dead bodies in his freezer until he can transport them to the headquarters for the conservation group. There they are collected and some of them are given to museums. “Before there was a pandemic, I went back to work and did my rounds. After that, I put them in my office freezer.” He adds that no one noticed.

Volunteers in the USA and Canada are active in multiple communities. There is a growing number of local governments that are enacting legislation to protect birds and buildings. According to the nonprofit American Bird ConservancyNew York’s law has been one of the most successful additions. Daniel Klem is thrilled after spending almost 50 years studying bird collisions. He finally gets the awareness he’s been seeking.

“Climate Change is also a serious issue that nobody wants to distract from.” It’s complex and it will take us some time to understand it all and convince people to be responsible.” he said. “Bird collisions are something we could solve tomorrow. It’s not difficult; we just need to have the will to do it.

Edited and written by Ruby Russell