[ad_1]

Sunscreen bottles are frequently labeled as “reef-friendly” and “coral-safe.” These claims generally mean that the lotions replaced oxybenzone – a chemical that can harm corals – with something else. These other chemicals are more beneficial to reefs than oxybenzone.

This question led to Contact usTwo Environmental chemistsTo team up with BiologistsWho studies? Sea anemones as a model corals. Our goal was to uncover how sunscreen harms reefs so that we could better understand which components in sunscreens are really “coral-safe.”

In our new studyScience published our findings that corals and sea anemones absorb oxygenone. Their cells convert it into phototoxinsThese molecules are toxic in sunlight but harmless in the dark.

Amanda Tinoco, CC BY -ND

Protecting people, harming reefs

Sunlight can be made up of many wavelengths of light. Longer wavelengths – like visible light – are typically harmless. But light at shorter wavelengths – like ultraviolet light – can pass through the surface of skin and damage DNA and cells. Sunscreens such as oxybenzone absorb most of the ultraviolet light and convert it into heat.

Recent decades have seen coral reefs around the globe suffer from severe damage. Warming oceans and other stressors. Scientists believe that sunscreens from swimmers and wastewater discharges could also harm corals. They carried out lab experiments and found that oxybenzone concentrations as low at 0.14 mg per Liter of seawater could be harmful. Coral larvae can be killed in 24 hours or less. Although most field samples have lower sunscreen concentrations than others, there is one popular snorkeling spot in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Contains up to 1.4 mg of oxybenzone for every liter of seawater – more than 10 times the lethal dose for coral larvae.

Fvasconcellos via WikimediaCommons

These researches and a variety of other sources were likely to inspire you. Other studies Showing damageTo Marine life, Hawaii’s legislators VotedIn 2018, to ban oxybenzone, and another ingredient in sunscreens. Soon after, legislators in other areas with coral reefs like the Virgin Islands, Palau ArubaThey also implemented their own bans.

There are still some open debateIt is not clear whether the levels of oxybenzone in our environment are high enough for reef damage. However, everyone agrees that these chemicals can cause damage under certain conditions. It is therefore important to understand their mechanism.

Djordje Vuckovic, CC BY -ND

Toxins or sunscreen

Although laboratory evidence has shown that sunscreen can cause coral damage, very little research has been done to explain how. Some studies suggested that oxybenzone may be harmful to corals. mimics hormonesthereby disrupting reproduction and development. Our team also found intriguing the possibility that sunscreen acts as a barrier to reproduction and development. Corals are exposed to light-activated toxins.

To test this, we used sea anemones from our colleagues as a model for corals. Sea anemones, corals, and algae are closely related. It is. It is extremely difficult to conduct coral experiments in a laboratory environment.Anemones are often better for lab-based research like ours.

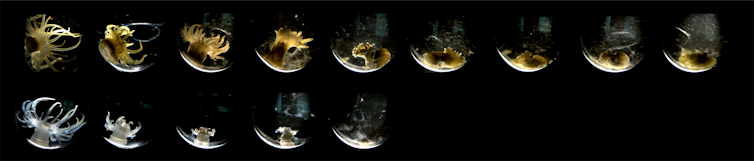

21 anemones were placed into test tubes filled with seawater, under a lightbulb that emitted the full spectrum. We covered five anemones in an acrylic box that blocks the UV light that oxybenzone is known to interact with. Then, we exposed all five anemones with 2 mg of Oxybenzone per liter seawater.

The anemones under the acrylic box were our “dark” samples and the ones outside of it our control “light” samples. Anemones, like corals, have a translucent surface, so if oxybenzone were acting as a phototoxin, the UV rays hitting the light group would trigger a chemical reaction and kill the animals – while the dark group would survive.

The experiment was conducted for 21 days. The experiment ended on Day Six when the first anemone from the light group died. By Day 17, All of them had died. During the three-week period, however, none of the anemones from the dark group died.

Christian Renicke, CC BY -ND

Metabolism converts Oxybenzone into phototoxins

It was surprising that a sunscreen behaved as a phototoxin in the anemones. We ran a chemical experiment using oxybenzone. The results showed that it acts as a sunscreen, and not as a toxic substance. It’s only when the chemical was absorbed by anemones that it became dangerous under light.

Every organism absorbs a foreign chemical. It is then determined by its cells how to get rid of it. Our experiments indicated that one of these processes was the transformation of oxybenzone into an oxin.

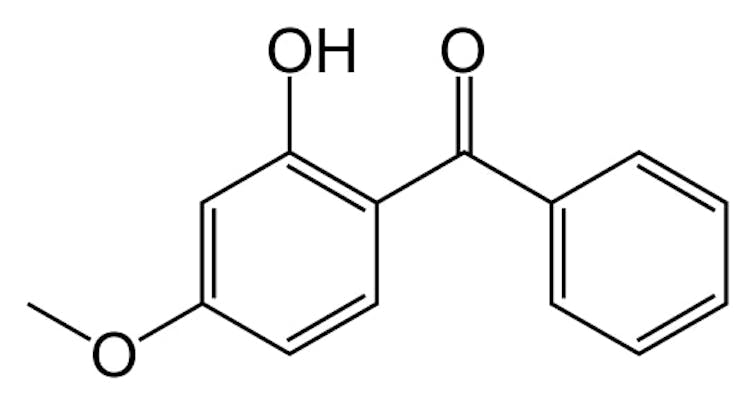

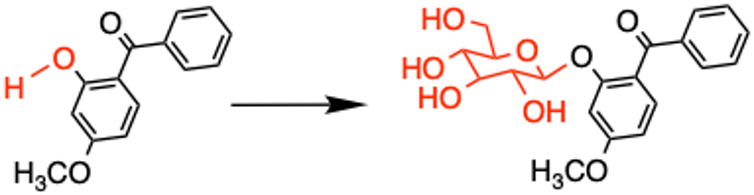

We tested this by analyzing the chemicals formed in anemones when they were exposed to oxybenzone. We learned that our anemones had replaced part of oxybenzone’s chemical structure – a specific hydrogen atom on an alcohol group – with a sugar. It is possible to replace hydrogen atoms on alcohol group with sugars. Plants AnimalsChemicals are often made less toxic and more watersoluble to make them easier to excrete.

Djordje Vuckovic, CC BY -ND

This alcohol group is removed from oxybenzone and oxybenzone ceases functioning as a sunscreen. Instead, it retains the energy it absorbs from UV radiation and kicks off a series. Rapid chemical reactionsThat Damage to cells. The anemones are not going to make sunscreen a harmless, easy to remove molecule. Oxybenzone can be converted into a potent, sun-activated xin.

We discovered something unexpected when we did similar experiments with mushroom corals. Despite the fact that we were unable to find any evidence of a connection between mushroom corals and humans, Corals are more susceptible to stressors that sea anemones than coralsThey survived the eight-day experiment without succumbing to oxybenzone or light exposure. The coral produced the same phototoxins as oxybenzone, but all the toxins were stored in the symbiotic bacteria living in the coral. The algae appeared to absorb the phototoxic byproducts, and probably protected their coral hosts.

Christian Renicke & Djordje Vuckovic, CC BY -ND

We believe that corals would have died from phototoxins if they didn’t have algae. It is impossible to keep corals alive in a lab without algae, so we tried anemones with no algae. These anemones died two times faster and had nearly three times as much phototoxins in their cells than anemones that were grown with algae.

Coral bleaching, ‘reef-safe’ sunscreens and human safety

We believe there are some important lessons to be learned from our research into how oxybenzone harms corals.

First, Coral bleaching events – in which the corals expel their algal symbionts because of high seawater temperatures or other stressors – likely leave corals particularly vulnerable to the toxic effects of sunscreens.

Second, it’s possible that oxybenzone could also be dangerous to other species. In our study, we discovered that oxybenzone can be turned into a potentially toxic substance by human cells. If this happens inside the body, where no light can reach, it’s not an issue. It could be a problem if it happens under the skin where light can cause toxins. Previous studies have shown that oxybenzone may be beneficial. People could be exposed to health risks, and some researchers recently It is important to conduct more research on its safety.

Finally, the chemicals used in many alternative “reef-safe” sunscreens contain the same alcohol group as oxybenzone – so could potentially also be converted to phototoxins.

We hope that our combined results will lead us to safer sunscreens and aid in protecting reefs.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]