[ad_1]

China’s surprise pledge to reach “carbon neutrality” before 2060 could cut global warming this century by 0.25C and raise the country’s GDP, our new analysis shows.

The significant new announcement, made by president Xi Jinping at this week’s UN General Assembly, means that more than one sixth of the world’s population – and around a third of its CO2 output – has, overnight, been committed to net-zero emissions within 40 years.

We used Cambridge Econometrics’ E3ME macroeconomic model to analyse the implications of the pledge, finding that China’s CO2 emissions would need to fall rapidly to reach net-zero by 2060.

上微信关注《碳简报》

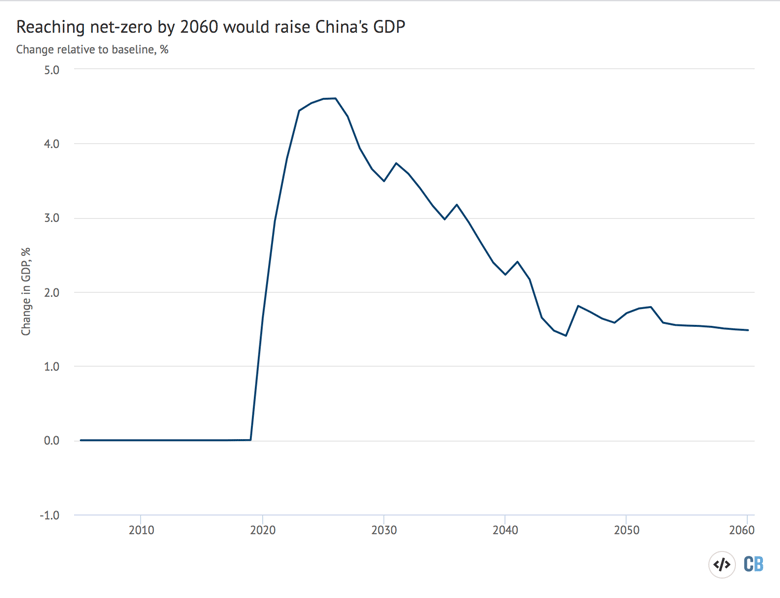

The huge scale of investments required to do this would raise China’s GDP by as much as 5% later this decade, with a modest ongoing positive impact due to reduced fossil-fuel imports.

China’s investments would not only drive dramatic reductions in its own CO2 emissions, but would also lower the cost of clean energy, creating a positive “spillover” effect in other countries.

In total, the pledge could mean global warming this century reaching around 2.35C, some 0.25C lower than the level expected in our baseline – even if others do not raise their own climate goals.

Path to zero

We recommend a range of policies to help China reach net-zero CO2 emissions by 2060. The foundations are provided by a combination of energy efficiency rules and carbon pricing, built on the country’s nascent emissions trading scheme.

China would also need to offer support for specific technologies to accelerate existing trends in their uptake – for example, via feed-in tariffs for renewables or subsidies for electric vehicles. It would also need ensure that no new coal plantsare constructed, highlighting the importance of regulation in directing markets to net-zero emission.

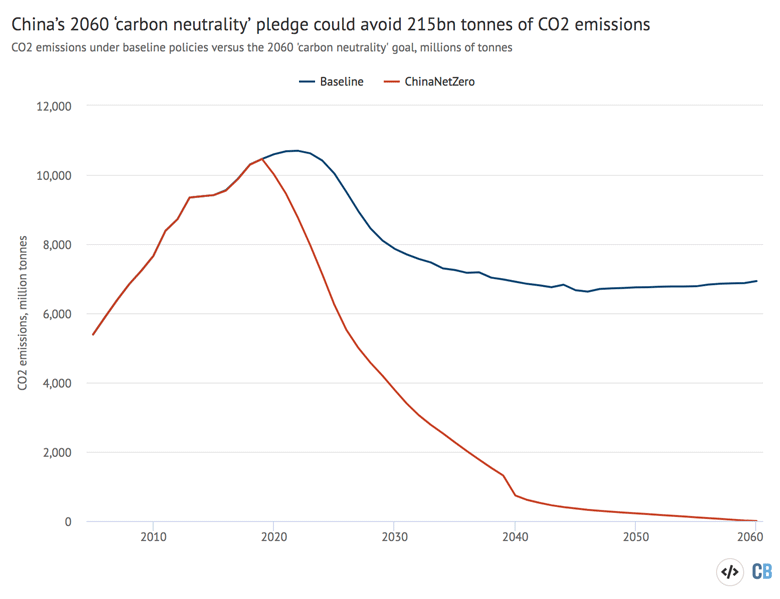

These interventions would dramatically cut China’s CO2 emissions over the next 40 years, relative to what we would expect under existing policies and technology trends. As shown in the chart below, this would prevent China from releasing 215bn tonnes CO2 over the next forty years.

Based on existing policies and technology trends, modelled CO2 emissions in China (baseline, blue) versus a pathway toward net-zero in 2060 (ChinaNetZero red), millions upon millions of tonnes of carbon2. Source: Cambridge Econometrics modelling. Carbon Brief Chart Highcharts.

It is worth noting that, in our modelling, the current policy baseline (blue line in the chart above) already suggests a rapid peak in China’s CO2 emissions before 2025, followed by a decline and longer-term plateau. Other research has also shown that China’s CO2 emissions have declined over the past few years. already suggested the country could peak well before its previously pledged goal of “around” 2030.

Our baseline modelling shows that the CO2 emissions peak is early. low-cost solarWind is starting to replace coal-fired generation in electricity grid. This gives an insight into one of the potential motivations for China’s new carbon neutrality pledge.

Global impact

The reduction in China’s CO2 emissions that we modelled – a cumulative 215GtCO2 – is hugely significant relative to the remaining carbon budgetLimiting global warming to 1.5- or 2C.

But this is not the only way that the pledge could cut emissions, because actions in China can also cause “spillover” effects in the rest of the world. We’ve seen this already with solar cells, where high levels are required in China. driven down pricesAll over the globe

This means that, even if the rest of the world did not implement any new climate policy in response to China’s raised ambition, emissions would still fall in other countries. This is a significant reduction in emissions, with a savings of more 500m tonnes (MtCO2) per annum according to our modeling.

Our results show that the 2060 promise to reduce CO2 could prevent 0.25C in warming this century. This would result in temperatures rising to 2.35C above the pre-industrial level by 2100, rather than the 2.59C we had in our baseline scenario.

Our results are very similar to the findings published by Climate Action TrackerThe pledge could reduce global warming by 0.2 to0.3C, according to.

We found that not all spillover effects are positive. China’s rapid decarbonisation would reduce oil demand, meaning that global prices would fall by up to 5% and the transition to electric vehicles outside China would slow, relative to the baseline and assuming no additional policy interventions.

Larger economy

Decarbonising the world’s current largest emitter will not be cheap. The carbon price in our modelled pathway to carbon neutrality reaches $250/tCO2, in today’s prices.

Relative to the baseline, investment in the power sector alone increases by $4tn (today’s prices, non-discounted) over the 40 years – and millions of people currently work in the coal sector.

However, most of the technology and equipment required for decarbonisation are made in China. The country also has the potential to produce more. The country would also be able to significantly reduce its imports of fossil fuels while simultaneously boosting its exports. effortsTo increase self sufficiency.

As a result, China’s GDP increases in the net-zero scenario relative to the baseline, as shown in the chart below, with significant positive impacts particularly in the short term.

Change in China’s GDP in the net-zero pathway, relative to the baseline, %. Source: Cambridge Econometrics modelling. Carbon Brief Chart Highcharts.

The difference would be large early on due to all the investment in renewables. But, the long-term benefits would be smaller because of lower fossil fuel import costs. China’s energy security would also be improved.

Get our free Daily BriefingFor a digest of the last 24 hours of energy media coverage, visit our Weekly BriefingFor a complete round-up of our content for the past seven days, click here Enter your email below.

On the flip side, GDP in the rest of the world would fall slightly (<1%), driven by lower export revenues for oil and gas-producing countries – assuming no further policy response outside China. Global GDP would increase overall, with China’s rise outweighing other losses.

It is important that these results do NOT include feedbacks from climate change. The physical effects of climate changes may be significant by 2060.

Localised pain

The model results show that China will see an overall benefit from the new targets. However, there will be localised pain – for example, those millions of coal workers who may struggle to find other jobs and the parts of China that rely on coal extraction would be hit hard.

President Xi’s announcement suggests that he thinks this transition can be managed, with the benefits outweighing the costs. This is in contrast to the US’s position, although the upcoming election may change that.

It is evident that China has set a precedent at a time where many other countries are weighing their climate commitments.

Acknowledgements

This story has sharelines

[ad_2]

Source link