[ad_1]

Many numbers are swirling around climate negotiations at the UN summit in Glasgow, COP26. These include global warming targets of 1.5℃ and 2.0℃, recent warming of 1.1℃, remaining CO₂ budget of 400 billion tonnes, or current atmospheric CO₂ of 415 parts per million.

It’s often hard to grasp the significance of these numbers. However, studying ancient climates can help us to appreciate their scale in relation to past natural events. Scientists can also use ancient climate change information to calibrate their models, and thus improve their predictions for the future.

IPCC AR6, chapter 2

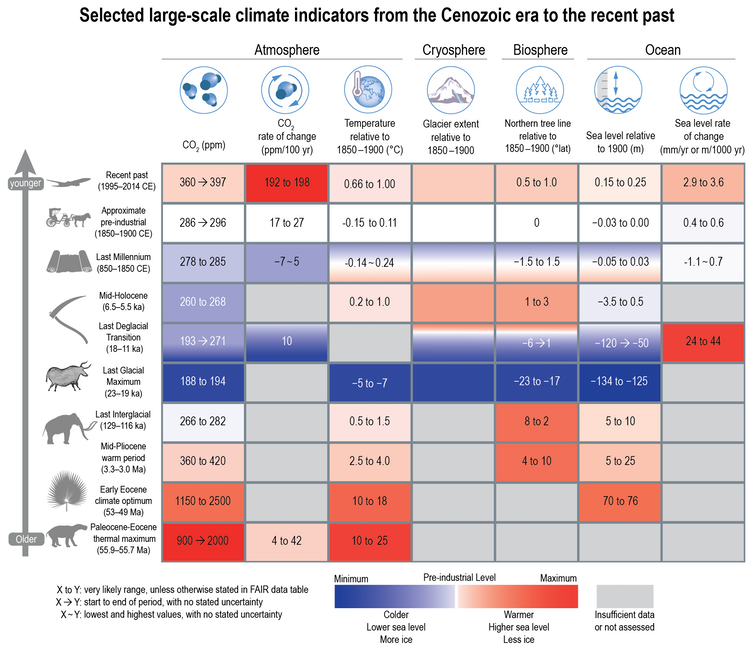

Recent work, summarized at the latest reportScientists have been able to improve their understanding of past climate changes through the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. These changes can be found in rocky outcrops as well as sediments from the seafloor and lakes. They also appear in polar Ice Sheets and other shorter-term archives like tree rings and corals. Scientists have been able to access more of these archives and become better at using them. This allows us to compare the current and future climate changes with the past and provides context to the numbers used in climate negotiations.

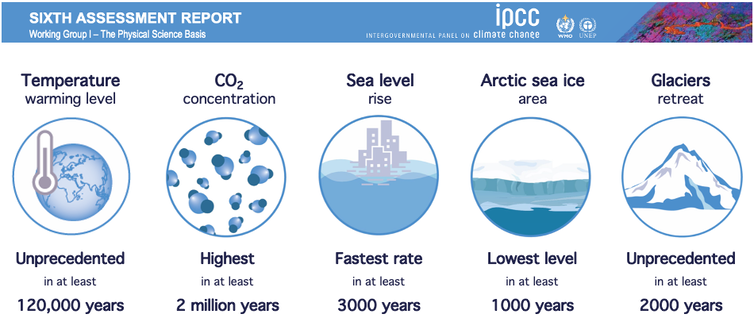

For instance one headline finding in the IPCC report was that global temperature (currently 1.1℃ above a pre-industrial baseline) is higher than at any time in at least the past 120,000 or so years. That’s because the last warm period between ice ages peaked about 125,000 years ago – in contrast to today, warmth at that time was driven not by CO₂, but by changes in Earth’s orbit and spin axis. Another finding regards the rate of current warming, which is faster than at any time in the past 2,000 years – and probably much longer.

The geological record can also reconstruct past temperatures. For instance, tiny gas bubbles trapped in Antarctic ice can record atmospheric CO₂ concentrations back to 800,000 years ago. Scientists can also turn to microscopic fossils found in seabed sediments for further evidence. These properties (such as the types of elements that make up the fossil shells) are related to how much CO₂ was in the ocean when the fossilised organisms were alive, which itself is related to how much was in the atmosphere. As we get better at using these “proxies” for atmospheric CO₂, recent work has shown that the current atmospheric CO₂ concentration of around 415 parts per million (compared to 280 ppm prior to industrialisation in the early 1800s), is greater than at any time in at least the past 2 million years.

IPCC AR6, Chapter 2 (modified Darrell Kaufman).

Other climate variables may also be available compared to past changes. These include the greenhouse gases methane (now higher than ever in at most 800,000 years), late-summer Arctic sea ice (smaller than ever in the past 1,000 years), glacier retreat. Sea level is rising faster than any point in at minimum 3,000 years. Ocean acidity is unusually acidic compared with the past 2,000,000 years.

Additionally, climate models can be used to compare the future to predict changes. For instance an “intermediate” amount of emissions will likely lead to global warming of between 2.3°C and 4.6°C by the year 2300, which is similar to the mid-Pliocene warm period of about 3.2 million years ago. Extremely high emissions would lead to warming of somewhere between 6.6°C and 14.1°C, which just overlaps with the warmest period since the demise of the dinosaurs – the “Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum” kicked off by massive volcanic eruptions about 55 million years ago. Humanity is currently on a path to compressing millions upon millions of years of temperature changes into just a few hundred years.

Daniel Eskridge / shutterstock

The distant past can be used to predict the near future

The IPCC’s latest report makes use of historical time periods to refine its projections of climate change. This is the first IPCC report. Future projections were produced in previous IPCC reports by simply combining results from all climate models and using their spread to measure uncertainty. For this report, the temperature, rainfall, and sea level projections were based more heavily on models that do the best job of simulating climate changes.

Part of this process was based on each individual model’s “climate sensitivity” – the amount it warms when atmospheric CO₂ is doubled. The “correct” value (and uncertainty range) of sensitivity is known from a number of different lines of evidence, one of which comes from certain times in the ancient past when global temperature changes were driven by natural changes in CO₂, caused for example by volcanic eruptions or change in the amount of carbon removed from the atmosphere as rocks are eroded away. Combining estimates of ancient CO₂ and temperature therefore allows scientists to estimate the “correct” value of climate sensitivity, and so refine their future projections by relying more heavily on those models with more accurate climate sensitivities.

The past climates indicate that all aspects of the Earth system have experienced changes that are unprecedented in at minimum thousands of years. Global warming will increase if emissions are not drastically and rapidly reduced. This is something that hasn’t been seen in millions of years. Let’s hope those attending COP26 are listening to messages from the past.

This story is part of The Conversation’s coverage on COP26, the Glasgow climate conference, by experts from around the world.

The Conversation is here to help you understand the climate news and stories. More.

Source link