Arifsyah Nasution was happy to hear that the Indonesian government had announced plans to make Indonesia’s fishing industry more sustainable by 2019. Greenpeace’s Ocean Campaign Leader in Southeast Asia has long raised concerns about endangered fish stocks within Indonesian waters. He is not optimistic that the situation will improve by 2025.

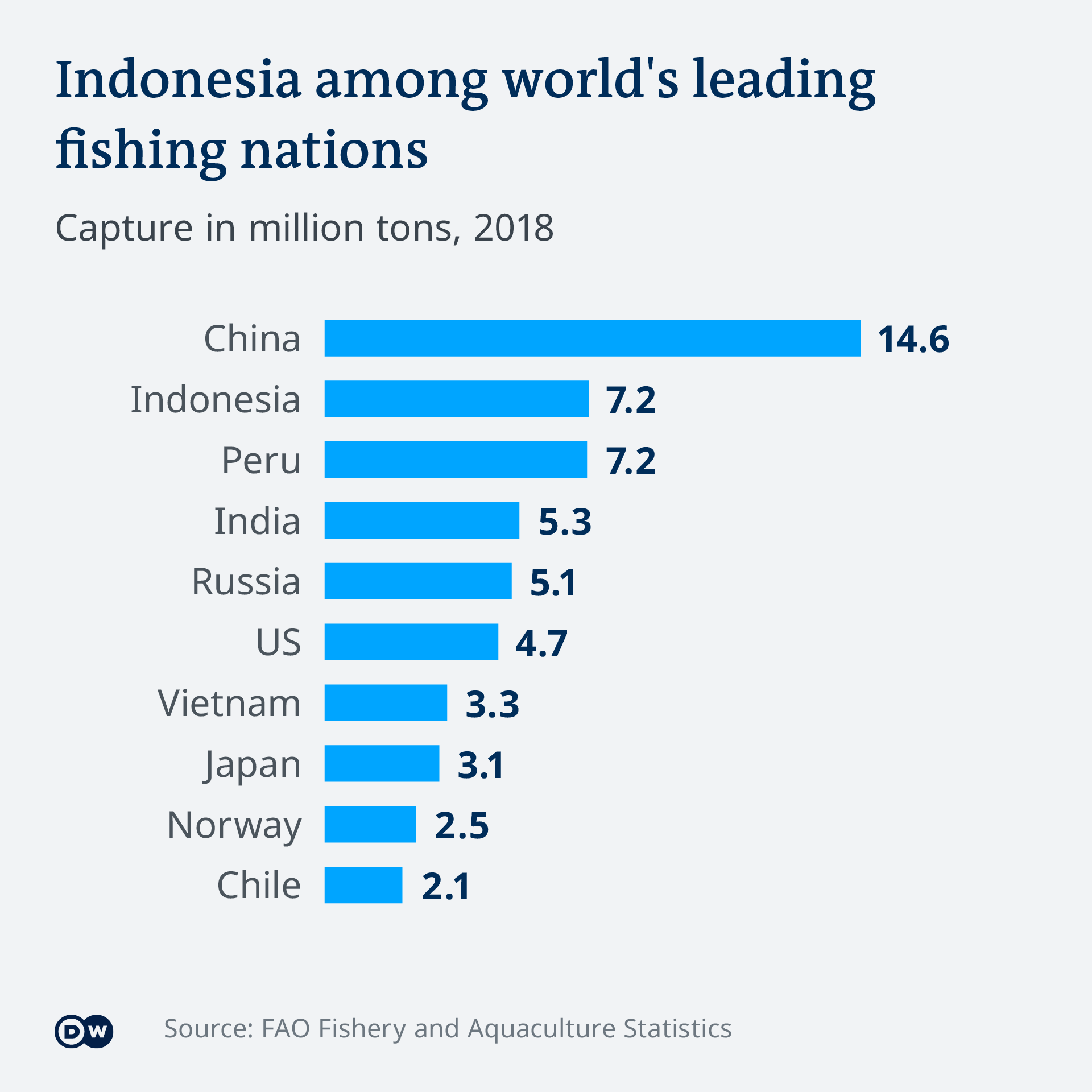

Indonesia is second in the world for fishing, with more than 7 million tons of catch each year. The majority is consumed domestically by the 270 million population, who consume more seafood and fish than the global average.

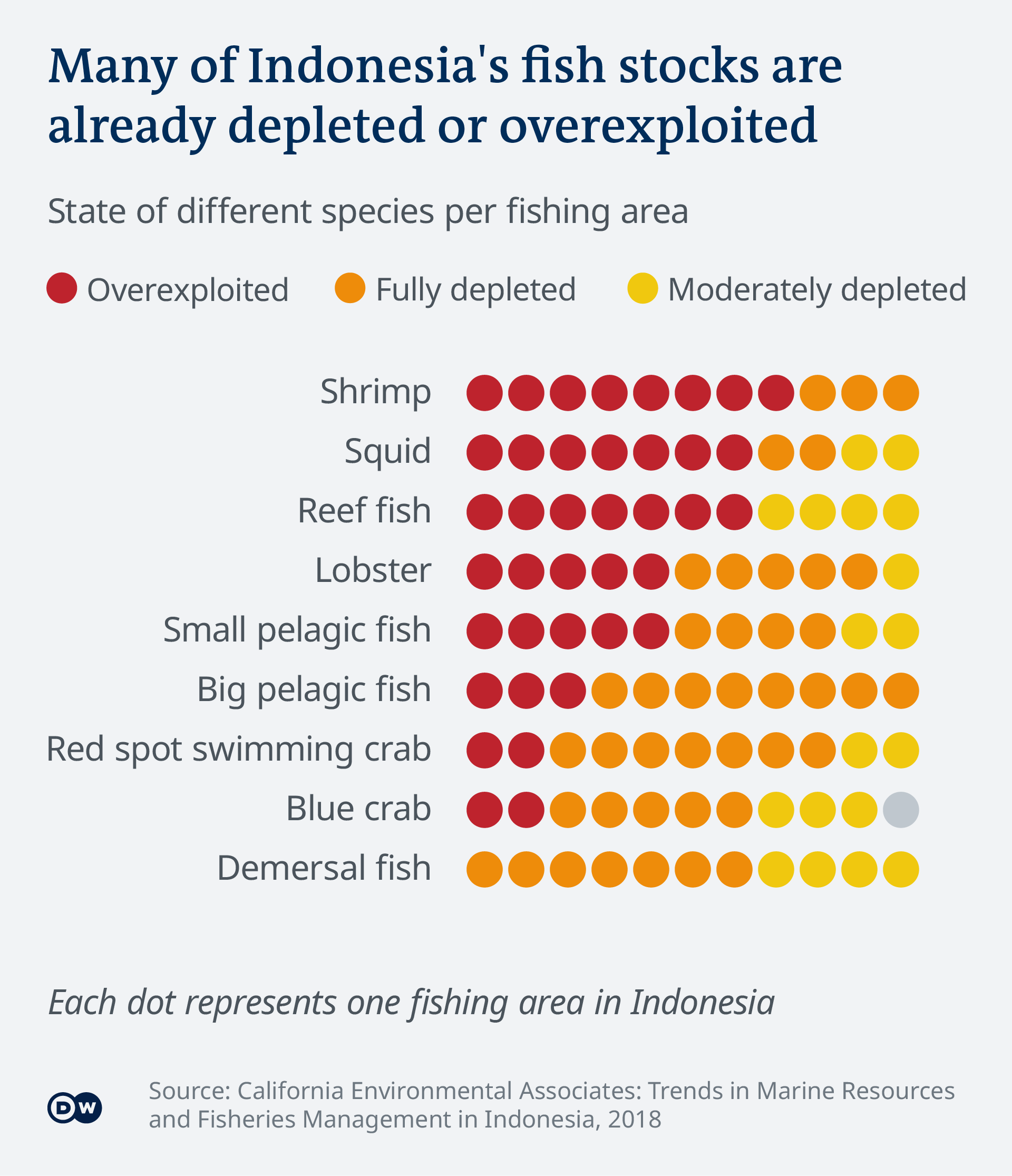

This has wide-ranging implications: The majority of Indonesia’s fish stocks are already depleted or overfished. According to the Marine Affairs and Fisheries Ministry, 90% of Indonesian boats draw their catch from areas that are already overfished and overcrowded with boats.

37% of the world’s marine animals live in Indonesian waters. Many of these species are threatened by fishing. Shrimp, as an example, are being overfished in more Indonesian waters than two-thirds. In other parts of the country, quotas have also been exhausted.

The alarming decline in stock levels is alarming. The problem is difficult to solve, however, as often the economic aspect, namely the sales volume, is the main focus. According to Nasution, it’s not about the global market demand but the survival of the Indonesian people.

Subsidies as drivers for overfishing

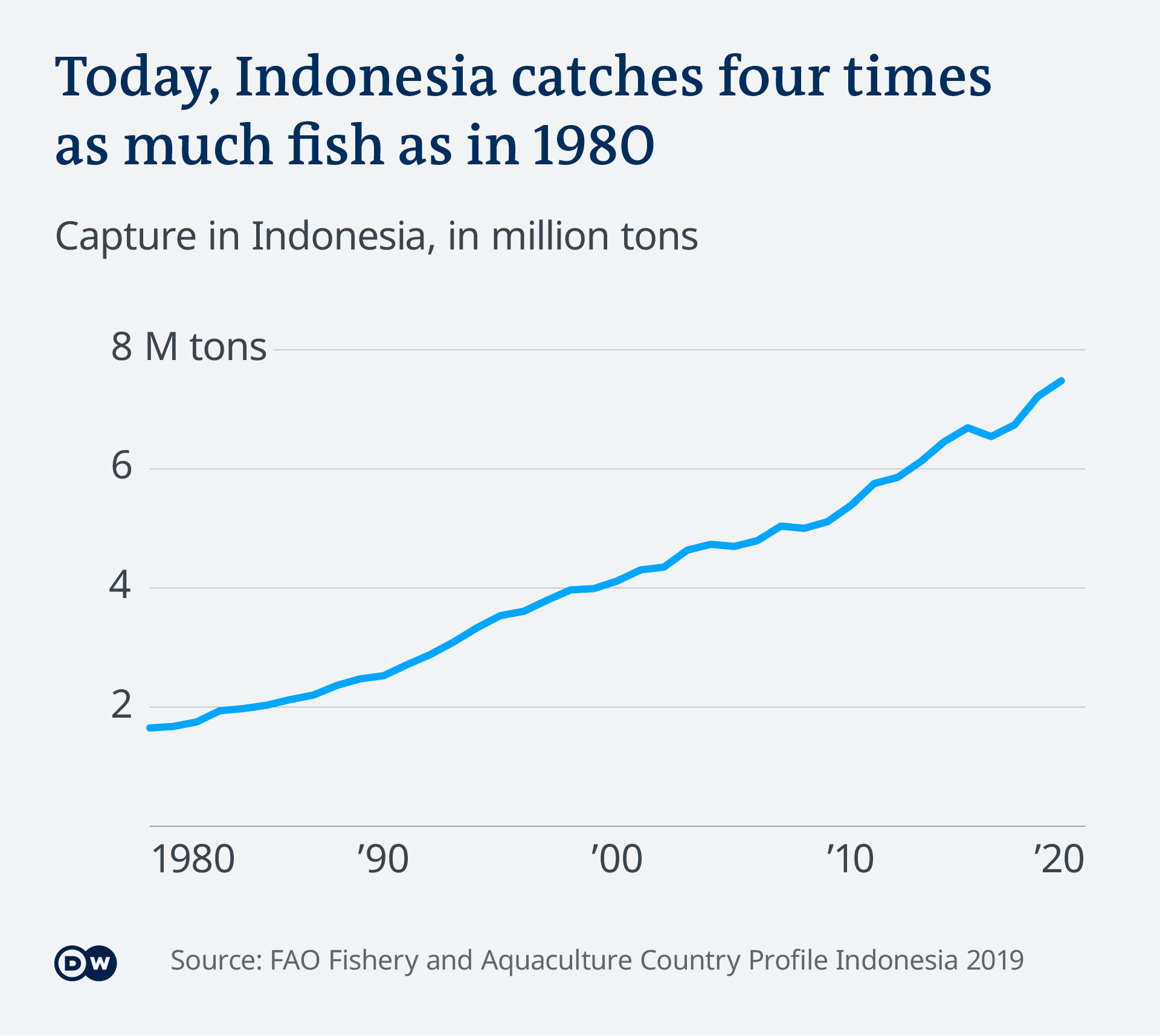

Subsidies The fisheries sector in IndonesiaIn the last decade, steady increases in catch have been attributed to lower fuel prices and tax deductions.

Many scientists are critical of them. Subsidies that encourage overfishing, loss or destruction of biodiversity and marine areas can be harmful. This can happen, for example, when fishing activities are pushed to the limit or when subsidies encourage unsustainable fishing practices. According to a study done by the University of British Columbia, more than 60% of global subsidies to the fishing industry could be harmful to the oceans.

The World Trade Organization has been advocating for the abolition of harmful subsidies in the fishing industry since 2001, but has so far not been successful. “Two years is too long to stop subsidies that finance the constant overexploitation our oceans. […]In a speech on June’s World Ocean Day, Ngozi Okonjo Iweala, Director General of WTO, stated that we need these rules for the protection of the environment, food security, and livelihoods around the world.

Subsidy change from harmful to beneficial

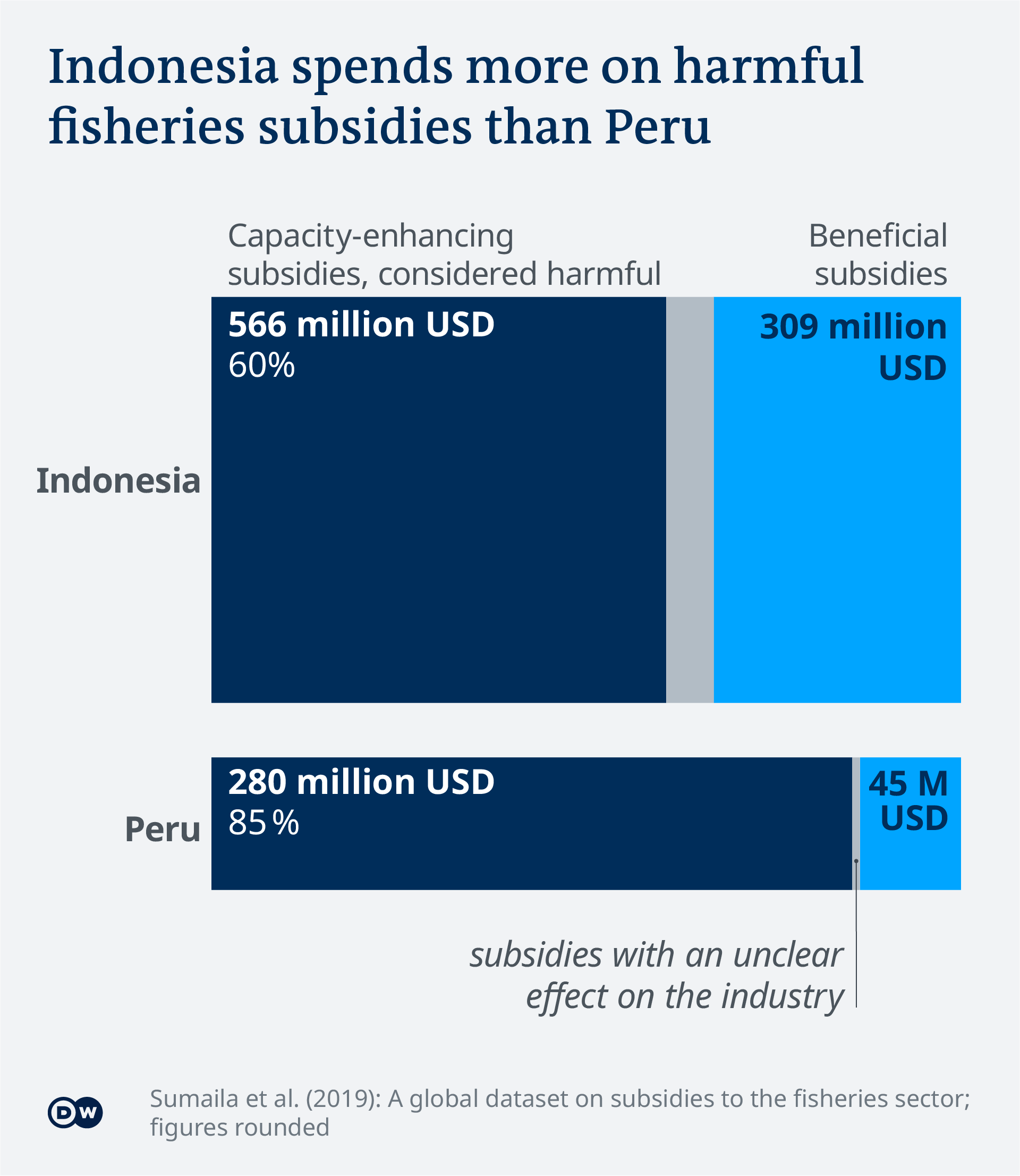

Indonesia has been subsidizing fisheries more heavily than any other developing country, spending more than $932million (825 million) in 2018. Peru, which captures almost as much, spends a third less than Indonesia on subsidies for its fishing industry.

Indonesia spends more on capacity enhancing harmful subsidiesPeru’s spending is 60% of total US dollars, but it is much higher as a percentage. These capacity-enhancing subsidies include support for boat construction and renovation, as well as larger projects like fishing port developments.

Experts say that subsidies are most beneficial to large-scale fishing fleets, even though small-scale fishing operations make up almost 95% of this sector.

However, targeted, beneficial subsidies can be a great way to preserve biodiversity and protect ecosystems. About one-third of Indonesia’s subsidy funds have been used to this end. Some funds were used to promote marine protected areas, which are designed to protect ecosystems from human exploitation.

Raja Ampat, an island in eastern Indonesia, is a good example. It was designated as a marine protected area in 2004. They now cover 4.6million ha (11.3 million acres) of land and are considered to be the most biodiverse protected areas in the world. There are more than 1,600 species of fish, and hundreds upon corals. Many tourists enjoy the abundance of fish but there are also poachers who have repeatedly caused harm by fishing with dynamite.

Raja Ampat is a success story worldwide for cooperation between NGOs and fishing communities. The NGOs emphasized research and communication to increase awareness and inform stakeholders. For example, the government emphasized more on creating structures such as a monitoring team to protect the area.

Raja Ampat, which is home to 75% world-famous stone corals, has been deemed the richest coral coral reef on Earth.

Protected areas cannot be established everywhere and it is not possible to eliminate harmful subsidies completely. There is a risk that entire industries will be destroyed if these funds are not available, according to Simon Funge-Smith (senior fishery officer at FAO’s Asia-Pacific regional office, Bangkok). He also warned that the consequences could be severe. “The loss and destruction of jobs is political dynamite.”

In Indonesia’s fishing industry, nearly 7 million people are employed. According to Indonesia for Global Justice (an NGO advocating fair-trade), small-scale fishermen would be affected if the government stopped all harmful subsidies.

Funge Smith stated that the government must be careful in planning, converting harmful subsidies to beneficial ones and ensuring the industry’s continued economic viability.

Politics hinder sustainable development

It is much easier said than done. In Indonesia’s Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, there has been very little continuity over the past few years. The minister in charge has changed multiple times since 2019. A ban on particularly dangerous trawl nets was temporarily lifted by the minister in charge in November 2020, before it was reinstated in July 2021.

Susi Pudjiastuti was Indonesia’s fisheries minister between 2014 and 2019. She strongly supported sustainable fishing and marine conservation.

Greenpeace’s Nasution explained that in order to promote responsible fisheries management, all stakeholders, including civil society, must continue to advocate for Indonesian fisheries issues at local and national levels.

He stated that the ministry’s knowledge in sustainable fishing has grown significantly over the past years. These efforts have been hindered by problems with the ministry’s leadership and the government’s focus on international investments. Foreign investment is primarily geared towards profit, which increases pressure on marine resources.

In 2014, the Indonesian government used extreme methods against illegal boats. They destroyed more than 300 domestic and foreign vessels in four years. According to a report, the number of fishing boats from foreign countries dropped by 25%, but local fishermen were more active. StudyThe ministry and American and Indonesian researchers at various universities. The authors observed a general recovery in fish stocks over that time, but warned that it could be destroyed by an increase in local fishing.

No data, no control

A key problem in fighting overfishing is the absence of reliable data to monitor compliance and make the necessary decision to protect the ocean. The mere size of the Indonesian archipelago, with its 17,500 islands and over half a million fishing boats, makes monitoring tricky. Most boats don’t have electronic devices onboard to aid tracking.

There are several pilot projects that could offer a solution. FishFace is one such pilot project. It automatically records fish caught and species with connected cameras on board. Remote monitoring is possible in real-time with this technology.

Funge-Smith and other observers are encouraged by such developments, even if Indonesia fails to achieve its stated goal of sustainable fisheries by 2025. He stated that “any progress towards that goal would be great.”

Arti Ekawati, DW, contributed to this article.

Edited and edited by: Gianna Grn, Anke Racper, Martin Kbler.