Public finance theory suggests environmental policies should be implemented at the federal level of government. This is due to the public good nature that environmental protection has and the existence of economies-of-scale in the provision environmental services. Decentralization could lead to a regulatory race at the bottom among competing jurisdictions in order to attract investment and residents, which could result in sub-optimal environmental outcomes. (Gray and Shadbegian, 2004). Common-pool problems and faster depletion of natural resources could also be a result of decentralisation. In addition, air pollution and emissions would be worse under decentralised standard setting due to inability to account interjurisdictional spillovers. (Banzhaf und Chupp 2010). The same argument can be applied to water pollution as well to a variety of outcomes related adaptation and mitigation to the effects of climate.

However, policy decentralisation could improve environmental outcomes. The exporting jurisdiction would see better outcomes if harmful activities could be exported to countries with more relaxed regulations. Net effects across the country are uncertain and could even increase within countries (Cutter & DeShazo 2007, Sigman (2014), Xia et.al. 2021). This may not necessarily be due to harmful horizontal rivalry, in the limited sense that minimum standards are set nationwide, but rather because of better recognition and appreciation of spatial differences in preferences. Furthermore, decentralization could lead to better overall outcomes if it improves monitoring & supervision by empowering subnational governments in regulatory matters.

In fact, the regional and local governments play a significant role in environmental policies. The subnational governments in most countries issue energy efficiency standards and land use regulations. They are not issued by the central government (de Mello 2021). Subnational governments are also responsible for managing natural disasters, whose risks are affected by climate change. Subnational jurisdictions also have a role in adapting to climate change. They account for the largest share of public investments. In many countries, regional governments are leading mitigation initiatives related the the introduction of carbon pricing. They sometimes act ahead of the national administrations. California’s experience and British Columbia’s in Canada are two examples.

A better understanding the intergovernmental aspects climate change mitigation/adaptation contributes to overall efforts for adapting the public finances to the challenge posed by climate change (Pisu and al. 2022, Thygesen et al. 2022). Effective intergovernmental coordination is essential for scaling up public investment, absorbing more severe weather-related costs, and deploying fiscal tools such as subsidies for innovations, support for vulnerable populations, and carbon taxes. These areas require more research (de Mello 202, Martinez-Vazquez 202).

The empirical evidence

Decentralization may have an impact on people’s attitudes and the design of policies related to the environment. A large body of empirical evidence, based on individual-level surveys-based data, shows that attitudes to the environment differ depending on personal and household characteristics, socioeconomic context, and political settings.

Yet, the empirical literature on policy decentralisation and the assignment policy responsibilities across different levels of administration is lacking. This leaves little to be able to explain how attitudes to the environment are affected. This gap was bridged in a new paper by de Mello and Jalles 2022 using individual-level data from World Values Survey.1Results show that decentralization does indeed lead to more favorable attitudes to the environment. This is after controlling for household and personal characteristics as well as country effects.

Our analysis shows that people who have experienced comprehensive decentralisation tend have more favorable attitudes to the environment than people who have not. Instead of asking survey respondents abstract questions about preferences and attitudes to decentralised Governance, which is a concept that is difficult for even well-informed people to grasp, we focus instead upon concrete experience with comprehensive Decentralisation through exposure during an individual’s adulthood to episodes of wide-ranging changes in the policymaking and administrative prerogatives of subnational layers. We used the Regional Authority Index calculated by Hooghe and colleagues to create a chronology of complete decentralization episodes across countries. (2016).

Cross-country evidence is sparse in the empirical literature on the relationship between decentralisation, environment-related tax and expenditure policies. This research was made possible by using aggregate country-level data from national accounts for a large number of advanced and developing economies. Instead of focusing on country-specific programmes or experiences as in most empirical literature, we instead focused our attention on aggregate data for all countries.2We compared the actual spending of government on environmental-related programs with the amount of environmental taxes that were collected by government.

Decentralization of revenue and spending functions to subnational levels of government is associated to higher spending on environmental-related programmes relative to GDP. This is after controlling for traditional public finance covariates. We also find a positive association with decentralisation and the collection of environment-related taxes revenue, even though parameters can be estimated less accurately than in the case government spending on environment, except for advanced economies.

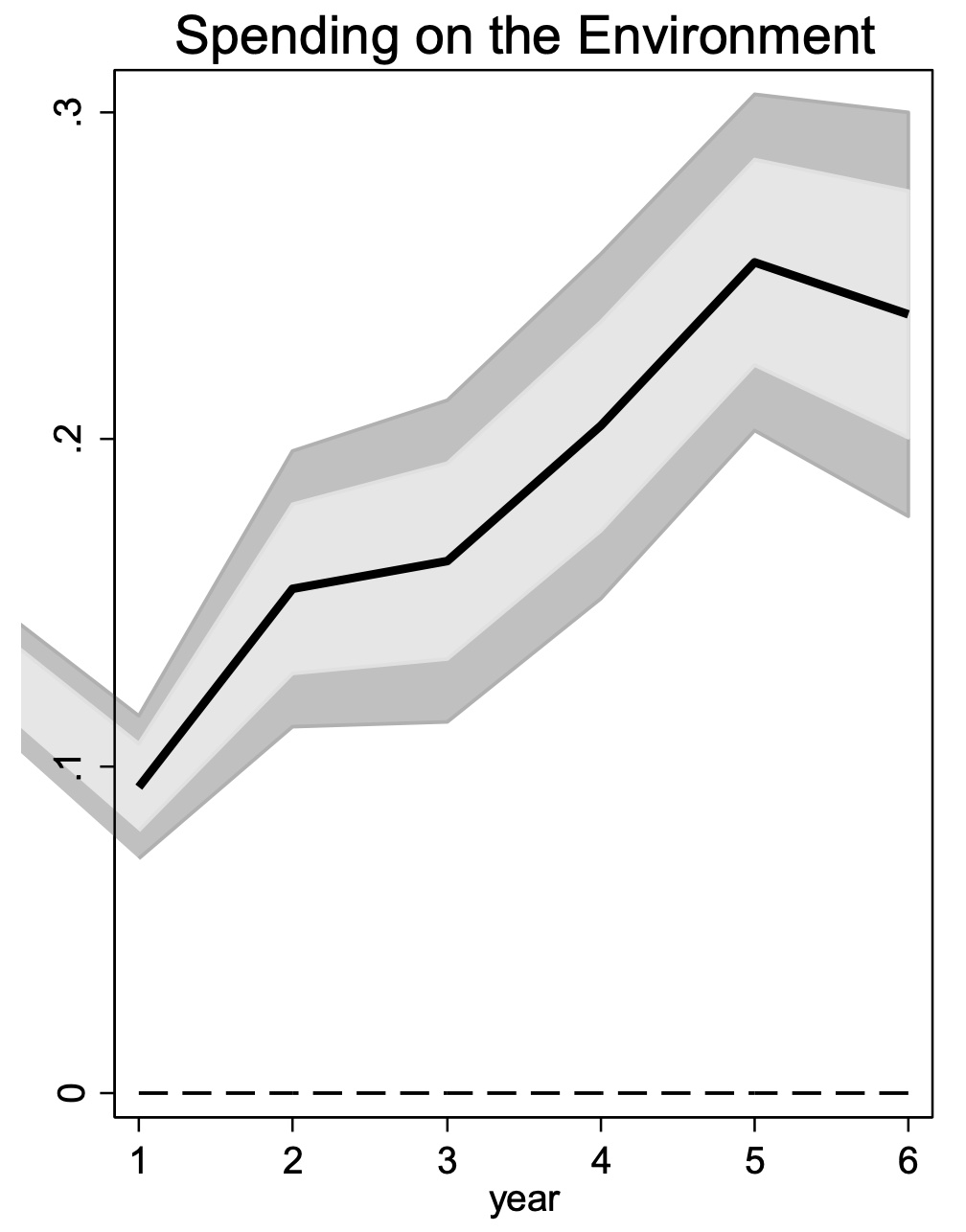

To determine the direction of causality, we examined the dynamic short- to medium-term effect of decentralisation upon environment-related spending. To determine the impulse responses of decentralisation shocks to comprehensive decentralisation episodes, we used the chronology. Figure 1 shows that after episodes of comprehensive centralisation, the government’s spending on the environment is stable (Figure 2).

Figure 1Dynamic effects of decentralisation and environmental fiscal outcomes

NotificationThe graph shows the estimated impulse reaction of spending on the environment to decentralisation shocks with 90 (68%) percent confidence bands. These confidence bands were computed using robust standard error clustered at country level. The x-axis displays years (k=1,6,6) following decentralisation shocks. Year = 0. See de Mello et Jalles (2022).

What can we learn from this analysis?

It is encouraging to see evidence from both individual-level survey data and aggregate national accounts data that shows a statistical association between environmental policy, attitudes to the environment, decentralisation and decentralization. This major finding suggests that countries with more decentralization may be better equipped for dealing with a variety of policy challenges, including climate change adaptation and mitigation. Although decentralization is not a policy tool that can be used solely to achieve environmental goals, it is part and parcel of the institutional environment in which environmental-related policies are designed and implemented. This influences attitudes, preferences, and outcomes.

References

S. Banzhaf and A. Chupp (2010), Environmental Quality in a Federation: Which level should regulate air pollution? VoxEU, 1 Jul.

Contorno L (2012). The Influence of Cosmopolitan Valuations on Environmental Attitudes. An International Comparison. Res Publica 17: 12-39.

Cutter, W.B., and J.R. DeShazo (2007). Environmental consequences of decentralizing the decentralization decision. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 53: 32-53.

de Mello L (2021), The Great Recession & the Great Lockdown: How do they shape intergovernmental relations?, I Lago (ed.), Handbook on Decentralization, Devolution, and the State, Edward Elgar, pp. 347-74.

de Mello, L. and J T Jalles (2022), The environment and decentralization: Survey-based evidence and cross-country evidence, REM Papers, No. 0215-2022, School of Economics and Management University of Lisbon.

de Mello, L. and J Martinez-Vazquez (2022), Climate Change Implications for the Public Finances and Fiscal Policy: A Agenda for Future Research and Filling the Gaps in Scholarly Work. Economics, forthcoming.

Elheddad (2020), The relationship between energy use and fiscal decentralization, and the importance and importance of urbanization: Evidence from Chinese Provinces Journal of Environmental Management 264: 1104-74.

Gelissen, J. (2007). Explaining Popular Support for Environment Protection: A Multilevel Analysis Of 50 Nations.Environment and Behavior 39: 392-415.

Gray, W.B., and R.J. Shadbegian (2004). Optimized pollution abatement Whose benefits are important and how big? Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 47: 510-34.

Hooghe (L, G Marks), A H Schakel and S Chapman. S Niedzwiecki, S Chapman and Shair-Rosenfield (2016). Measuring Regional Authority: Using a Postfunctionalist Theory for Governance Vol. Vol.

Ji, X (2020), Does fiscal centralization and eco-innovation promote a sustainable environment? A case study on selected fiscally decentralized nations Sustainable Development X: 1-10.

Konisky D M (2007). Regulatory Competition and Environmental Enforcement. American Journal of Political Science 51: 853-72.

Levinson, A. (2003), Environmental regulation competition: A status report with some new evidenceNational Tax Journal 56: 91-106.

Li, Q., B Wang, H Deng, and C Yu (2018). A quantitative assessment of global environmental protection value based on world values survey data 1994-2014. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 190: 593.

Pisu. M, F M DArcangelo. I Levin. (2022), A framework decarbonise the economy. VoxEU, 14 Feb.

H. Sigman (2014). Decentralization and Environmental Quality. An Inter-national Analysis on Water Pollution Levels. Land Economics 90: 114-30.

Thygesen N. R Beetsma M Bordignon M Szczurek M Larch M Busse M Gabrijelcic L Jankovics J Malzubris (2022), The post-pandemic era: Public finances and climate change, VoxEU 16 March

Torgler, B. and M. A Garca-Valias (2007). The determinants in individuals’ attitudes towards preventing damage to the environment. Ecological Economics 63: 536-52.

Xia and S, D You, Z Tang, and B Yang (2021), Analysis on the Spatial Effects of Fiscal Decentralization & Environmental Decentralisation on Carbon Emissions Under the Pressure of Officials’ Promotion Energies 14: 1878.

Wright, G D., K P Andersson. C C Gibson, and TP Evans (2016). Decentralization may help reduce deforestation if user group engage with local governments. PNAS 113.

Endnotes

1 The World Values Survey is also widely used to gauge attitudes towards the environment (Gelissen 2007, Torgler, Garca-Valias 2007, Contorno 2012. Li et al. 2018).

2Most empirical literature on decentralisation in the environment focuses on case studies in specific resource management and environmental protection programs. This is followed by evidence in the areas such as forest management (Wright and al. 2016), energy consumption (Elheddad et al. 2020), and emissions standards. (Konisky 2007, Ji. et. al. 2020, to name just a few.