[ad_1]

Fort McMurray Canada — The first mine opened when Jean L’Hommecourt was a young girl, an open pit where an oil company had begun digging in the sandy soil for a black, viscous form of crude called bitumen.

She and her family would pass the mine in their boat when they traveled up the Athabasca River, and the fumes from its processing plant would sting their eyes and burn their throats, despite the wet cloths their mother would drape over the children’s faces.

By the time L’Hommecourt was in her 30s, oil companies had leased most of the land where she and her mother went to gather berries from the forest on long summer days or hunt moose when the leaves turned yellow and the air crisp.

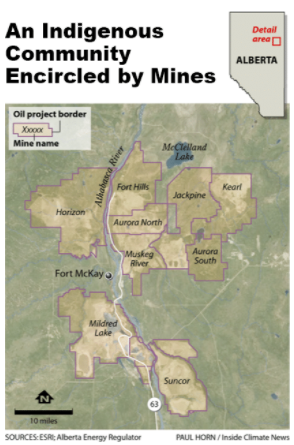

Today, the same land is near Fort McKay’s Indigenous community. It is surrounded today by mines that have engulfed an area larger than New York City. They have stripped away boreal forest, muskeg, and rerouted waterways.

Oil and gas companies like ExxonMobil and the Canadian giant Suncor have transformed Alberta’s tar sands—also called oil sands—into one of the world’s largest industrial developments. They have built waste ponds that leach heavy Metals into groundwater, as well as processing plants that emit nitrogen and sulfur oxides in the air, leaving a foul stench throughout the area.

The sands pump out more than 3 million barrels of oil per day, helping make Canada the world’s fourth-largest oil producer and the top exporter of crude to the United States. Their economic benefits are significant: Oil is the nation’s top export, and the mining and energy sector as a whole accounts for nearly a quarter of Alberta’s provincial economy. But the companies’ energy-hungry extraction has also made the oil and gas sector Canada’s largest source of greenhouse gas emissions. Despite the environmental consequences and the growing need for countries that use fossil fuels to reduce their carbon footprint, the mines continue expanding, digging up almost 500 Olympic-sized pools of earth every day.

COP26, a global climate conference held in Glasgow earlier this month, highlighted a persistent gap between what countries claim they will do to reduce emissions and what is actually required to prevent dangerous warming.

Scientists warn that oil production should immediately begin to fall. Canada’s tar sands are among the most climate-polluting sources of oil, and so are an obvious place to begin winding down. The largest oil sands firms have committed to reducing their emissions. They say they will rely on largely on government-subsidized carbon capture projects.

Some lawyers and advocates have pointed to the tar sands as a prime example of the widespread environmental destruction they call “ecocide.” They are pushing for the International Criminal Court to outlaw ecocide as a crimeThis is on a par to genocide and war crimes. While the campaign for a new international law is likely to last years, with no assurance it will succeed, it has drawn attention to the inability of countries’ existing laws to contain industrial development like the tar sands, which will pollute the land for decades or centuries.

Julie King, an Exxon spokeswoman, said that “ExxonMobil is committed to operating our businesses in a responsible and sustainable manner, working to minimize environmental impacts and supporting the communities where we live and work.”

Leithan Slade, a spokesman for Suncor, pointed to agreements the company has signed with First Nations, adding that “Suncor sees partnering with Indigenous communities as foundational to successful energy development.”

Despite those agreements, the mines’ ecological impacts are so vast and so deep that L’Hommecourt and other Indigenous people here say the industry has challenged their very existence, even as it has provided jobs and revenue to Native businesses and communities.

“The basis of all our Indigenous culture is on the land,” said L’Hommecourt, 58.

It was the threat to her mother’s traditional land that 20 years ago set her on a path of resistance. She was at a hearing to protest the proposed mine on a large portion of that land. She was recruited to work as an environment coordinator for Fort McKay First Nation. This Indigenous group is her home to help protect the land she could.

“That’s when I made my choice,” she said. “I’m going to fight for my mom’s land.”

Only one wayTo fully appreciate the scope of the tar sands is to see the mines from the air. Flying across the region from the north, the twisting channels of the Peace-Athabasca Delta, one of the world’s largest inland deltas, dominate the landscape, snaking through forest and marshlands with not a road or power line in sight.

This terrain opens up to a mixture muskeg, forest, and drylands. Here the sandy soil rises above the surface. Out of nowhere, straight lines emerge—a wide, unpaved highway and paths leading to squares carved out of the forest, where companies have explored for oil.

The mines are then visible. The sky is filled by billowing plumes. Flare stacks can send out flames. The forest’s green is replaced by vast black holes pockmarked with giant puddles. The dump trucks and shovels appear like toys from the air. They look like Tonkas digging in large sandboxes. The mines are terraced and have massive berms which hold back the waste lagoons from rising above the newly-digged pits. As the plane descends, the cabin smells tarry as it fills up with a foul stench.

“It’s just the most completely ludicrous approach to industrial and energy development that is possible, given everything we know about the impact on ecosystems, the impact on climate,” said Dale Marshall, national program manager with Environmental Defence, a Canadian advocacy group..

Boreal forest in Fort McMurray, Alberta gives way to a Tar Sands mine. Photo by Michael Kodas

Oil companies heat the bitumen sand and then use a mixture of solvents and water to extract it. In other parts of Alberta where the sands cannot be mined, bitumen can be melted and extracted underground by high-pressure steam. These deeper deposits cover more area than the mines, covering more than 50,000 miles.

Extracting oil takes enormous amounts of energy. consumed 30 percent of all the natural gas burned in Canada. Collectively, the mines and deep-extraction projects emit greenhouse gas emissions roughly equal those of 21 coal-fired power plants, and that’s just to get the crude out of the ground.

These operations also remove noxious air pollutants such as nitrogen oxides and sulfur oxides. Scientists have found trace amounts of these pollutants in snowpack and soils dozens of miles away.

The mines guzzle vast quantities of water, with nearly 58 billion gallons drawn from the region’s rivers, lakes, and aquifers in 2019, according to government figures. All that water is left at the other end is so laced with hydrocarbons and naphthenic acid, as well as carcinogenic heavy metals, that it cannot be released from its source. Instead, oil companies have been collecting these acutely toxic “tailings” in waste ponds, some of which routinely leak their contents into groundwater.

A report to the Alberta Department of the Environment was prepared in 1973 identified waste as a problem and recommended placing limits on the ponds’ size and duration of use. The idea was that the toxic elements would eventually settle out of the water in a matter of years. It is likely that the tailings may take years or even decades to separate naturally.

A tar-sands mine near Fort McMurray. The extraction of crude bitumen takes enormous amounts of energy and the mines produce toxic water. Photo by Michael Kodas

The ponds have exploded in size and now cover over 100 miles. They are growing every day. swell with millions of gallons of new toxic waste. According to regulatory filings the ponds are likely to expand well into 2030. Only a small fraction of the ponds have been reclaimed by companies, as required by law.

A coal-black mountain of debris towers above the water, just next to one pond. High voltage lines buzz overhead. Air cannons blast multiple times per minute over the pond, creating an explosive sound. Safety vests and helmets are worn by industrial iron scarecrows. The display and noise are designed to scare away millions of migratory bird species that arrive in northern Alberta every year, exhausted from their annual odysseys.

Sometimes even these defenses fail or the birds ignore them and land anyway—tens of thousands each year, according to a 2016 report to provincial regulators, obtained this year by The NarwhalCanadian news organization – a nonprofit

Ottilie Coldbeck, a spokeswoman for the Alberta Energy Regulator, which oversees the industry, said the research in the report “was not considered complete.”

Conservationists are worried that endangered whooping Cranes, which migrate to this area annually, could land in a lake. There are less than 900 of these cranes. However, a single flock landing could endanger the species.

White explorers TradesmenThey immediately set their sights on tar sands. In 1789, Sir Alexander Mackenzie reported seeing veins of “bituminous quality” exposed along the Athabasca River. Within a century, prospectors and geologists had identified “almost inexhaustible supplies” of petroleum in the area. The only thing that seemed to be a problem was the people living above it.

The Tar sands mining industry has engulfed an area that is larger than New York City. Fort McKay, an Indigenous community, is right in the middle. Even if no new mines were approved, the existing operations of Suncor, Syncrude and Imperial Oil could continue to grow within their leases for many decades.

Tar sands miners have engulfed an area larger than New York City. Fort McKay, an Indigenous community in the middle of them, is one of the largest. Even if no new mines were approved, existing operations of Suncor and Syncrude, Imperial Oil and Canadian Natural Resources could expand within their leases over the next decades.

In 1891, the superintendent general of Indian Affairs recommended drafting a treaty, “with a view to the extinguishment of the Indians’ title,” to open access to petroleum and other minerals. When a team was sent up the Athabasca eight years later to sign what would become Treaty 8, a member of the party named Charles Mair described giant escarpments rising on either side, “everywhere streaked with oozing tar, and smelling like an old ship.”

Mair was more skeptical. The Indigenous people used the substance for sealing canoes, and even to burn it like coal. “That this region is stored with a substance of great economic value is beyond all doubt,” he wrote. “When the hour of development comes, it will, I believe, prove to be one of the wonders of Northern Canada.”

But it would be many more years before that moment struck. The tar-sands were still far from reach until Americans, motivated by nationalistic ambitions invested huge sums of capital. In 1967, J. Howard Pew, of the Sun Oil Company, opened the first commercial mine, declaring, “No nation can long be secure in this atomic age unless it be amply supplied with petroleum.” A decade later, a second mine opened, called Syncrude, backed by a consortium of American oil companies and the Canadian government.

There were only two major mines for years. But the 21st century brought a growing global demand for oil and concerns that conventional sources of crude would run out. Oil prices surged, and Alberta’s massive pool of bitumen offered an opportunity to oil companies: No risky exploration was required, and unlike in other parts of the globe, Canada provided a stable, business-friendly government. Multinational corporations poured in cash, increased their reserves, and attracted tens to billions of dollars in new investments.

In a matter of ten years, the mines grew exponentially. Eight active tar sands mining operations form a 40 mile chain along the Athabasca river, with their massive shovels eating up the earth like a swarm of mechanical caterpillars.

The middle of all this is Fort McKay, a 765-person town. Despite the destruction of the land by the mines most people who lived here managed to survive, even as they were forced into smaller and smaller spaces.

L’Hommecourt keeps a cabin 20 miles outside of Fort McKay as the crow flies, but more than an hour’s drive, because the road has to loop between and around several mines and two deeper extraction projects.

Despite L’Hommecourt’s best efforts as an environmental coordinator, the mines have continued to encroach on her cabin, which sits on the land where she used to go with her mother. More and more workers have showed up in the area, stopping her along the road to tell her that she couldn’t hunt moose or that she was trespassing.

“‘You’re the trespasser,’” she tells them. “‘I shouldn’t have to be answering your questions, you answer mine. That’s my attitude.”

The land, she said, is where she can think in her language, Dene, “where in the outside world it’s all English.”

“You get that sense of belonging here,” she said, “and that’s what I want for our peoples, to have their land back.” She added, “If you have your land back, you have everything.”

Jean L’Hommecourt outside of her cabin near Fort McKay First Nation’s village. She used to hunt moose and gather berries with her mother. Now she’s surrounded by tar sands mines. Photo by Michael Kodas

When Pew’s Great CanadianThe opening of the Oil Sands mine in 1967 was a disappointment for Fort McKay. Jim Boucher, who was the First Nation’s chief for three decades, stated that Fort McKay residents were not happy.

He said that Sun Oil, now Suncor took over Tar Island, an important summer hunting ground and gathering ground. “There was no discussion, no consultation.”

The Fort McKay First Nation includes both Dene and Cree—the two main Indigenous groups that have lived in the region for centuries. For most of the 20th century, the fur trade provided the nation’s members with one of their few sources of income. It collapsed just as oil was gaining momentum, and the nation had no other choice but to turn to oil companies and their rapidly expanding mines.

“We had no choice,” Boucher said.

Boucher, who was appointed chief in 1986, founded the Fort McKay Group of Companies for the oil industry. Over the next decades, he managed partnerships with energy companies that would eventually bring in hundreds of millions of dollars to the community.

Fort McKay now revolves around oil sands. Boucher is proud to boast about the achievements of the oil sands industry. It has allowed the community build affordable housing and pay for education and eldercare. All members are eligible for quarterly dividends. Some, like Boucher have become relatively wealthy.

Many First Nations have also fought against development. Several have filed lawsuits against companies or regulators—The Beaver Lake Cree Nation, south of Fort McMurray, sued the federal and provincial governments in 2008, saying its treaty rights had been violated by the cumulative effects of development. The case remains pending trial, with a date for 2024 scheduled.

However, it can be costly and often fails to stop development.

“It’s David and Goliath here, we’re dealing with multi-billion dollar companies,” said Melody Lepine, director of government and industry relations for the Mikisew Cree First Nation. The regulatory process, she said, is built to approve the companies’ projects, even if it takes years. “It’s very, very difficult to get anybody to say, ‘No, you’re not going to get approved.’”

Each of the area’s First Nations has signed “impact benefit agreements” with the oil companies that can include limits on certain practices, like water withdrawals, quotas for hiring Indigenous people and direct payments to the nations. But even as the impact agreements have secured benefits for the First Nations, they’ve created a Devil’s bargain, deepening reliance on an industry that is consuming the land that was once the base of the Indigenous economy and culture. British sociologists Martin Crook (Damien Short), and Nigel South (Nigel South) have argued in support. that the concept of “ecocide” offers a “powerful tool” to recognize the particular damage caused by resource extraction to many Indigenous groups, because of their cultural, spiritual, and subsistence ties to ecosystems.

For three decades, Jim Boucher served as chief of Fort McKay First Nation. He managed partnerships with energy companies, which eventually brought in hundreds of millions of dollars for the community. Photo by Michael Kodas

Melody Lepine is the director of government relations and industry relations at the Mikisew Cree First Nation. She says that the regulatory process was designed to approve oil-and-gas projects. Photo by Michael Kodas

“They’re making us dependent on things that they make, things that they build,” L’Hommecourt said. “They want us to be dependent on those things so that we can give them our money, so we can give them our land and say, ‘Yeah, okay. I’ll trade it off.’”

L’Hommecourt, who is Boucher’s cousin, said she holds no resentment toward the former chief for tying their people’s fate to the industry.

“He did what he had to do, and as a chief I commend him,” L’Hommecourt said. “They call us the richest little First Nation in Canada.”

Boucher lost his grandfather’s cabin, where he learned to hunt and trap as a boy, to Syncrude’s mine. Boucher built a cabin to the north for his father. It now sits on a stamp of land that he said is surrounded by newer mines.

“It’s empty, that’s how the cabin is to me,” Boucher said. “So I don’t go there anymore. No joy.”

The mines are covered a staggeringly large area, but their impact on the environment reaches even farther.

Fort Chipewyan is located near the point where the Peace and Athabasca rivers flow into Lake Athabasca. It is approximately 90 miles from the nearest mine. The land here offers a glimpse into the past before oil and gas companies arrived. Except for a winter road that is difficult to maintain due to rising temperatures, there are no roads leading to the community. Indigenous residents can still hunt, trap, and trap in the unbroken boreal forest where wolves and wolverines roam and towering jack pines shade a thick and spongy mat lichens and moss below. The town abuts Canada’s largest national park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that is home to herds of wood bison and which the World Heritage Committee said in June was threatened by the expansion of the tar sands.

But while the nights are quiet and the air smells clean, the industry’s presence is strong even here. Kids zoom around town on ATVs, while the local supermarket displays boxes of 87” flatscreen TVs—“toys,” as some residents call them, that only those who work in the industry can afford to buy.

Despite being far from the development, the lake’s waters contain some of same compounds and heavy metals as those found in the upstream waste ponds.

Alice Rigney was a young girl when the waste ponds were not yet dug. Her family would go to their delta homestead before the freeze, and stay there until Christmas. She said that the men would trap the muskrats in the spring and the women would smoke the meat and dry the pelts. The spring bird hunt followed, with thousands of birds coming from the south.

In the late 1960s, however, the lake level dropped and the delta stopped flooding. A dam was built to fill the Peace River’s reservoir, and the Athabasca Tar Sands Development began. One day, she and her brother rode a snowmobile on the ice to go fishing in search of walleye. Then, they cooked their catch over an opened fire. The fish started to cook and the black grease began to seep out.

“The taste was gas or fuel,” Rigney said. She explained that they later learned that there had been a oil spillage upstream of the ice, and that the fishery had to close temporarily.

The tar sands mines have been poisoning the land and everything that it feeds for years. Everyone seems to know someone who has died of cancer or another disease—Rigney survived breast cancer, which ran in her family, and her husband survived colon cancer. However, the appearance of rare cancers in 2004 attracted more attention.

Rigney was working as a physical therapist’s assistant at the health clinic one day when a doctor approached her for help arranging travel, saying a jaundiced patient needed to be flown to Fort McMurray for treatment. The man’s illness was soon diagnosed as an aggressive type of bile duct cancer called cholangiocarcinoma. He died shortly thereafter.

Others developed the disease, which is rare in Canada. In 2010, there were a total of 58 cases. paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found elevated levels of numerous “priority pollutants,” including mercury, lead, nickel, and other heavy metals, in the river downstream of oil sands development, as well as in Lake Athabasca and in snow samples.

Three years later another study in the same journal examined lake sediments surrounding Fort McMurray and found that levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, a group of chemicals that includes cancer-causing compounds, started rising in the 1960s and 1970s, when oil sands development began. Researchers discovered elevated levels in a lake that was dozens of kilometres from the mines.

The Syncrude operation is north of Fort McMurray. Fort Chipewyan residents, located 90 miles downstream of the nearest mine, have suspected for years that the tar sands operations are poisoning their land. Photo by Michael Kodas

The Athabasca Chipewyan and Mikisew Cree First Nations commissioned Stéphane McLachlan, an environmental scientist at the University of Manitoba, to test the tissues of animals, and in 2014 he released a report, finding elevated levels of toxic pollutants — including arsenic, mercury, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons—in the flesh of moose, ducks, and muskrats in the region. The study found that community members were not exposed at levels sufficient to cause health problems. However, many people stopped eating wild game because they were afraid it might be contaminated.

Although the study couldn’t prove that the cancers resulted from pollution from the mines the researchers found a correlation between cancer rates in the community and working in the mines. They also found a correlation with eating more traditional foods, including fish.

Provincial officials acknowledge that the mines’ waste ponds leak into groundwater. To “limit the risk” that this seepage will spread farther, the Alberta Energy Regulator requires companies to install drains, wells, sumps, and underground walls to capture and contain the contamination, said Coldbeck, the agency spokeswoman.

Federal and provincial officials refute research linking groundwater contamination to waste ponds. They cite other studies that show the compounds may be naturally occurring in groundwater due to their presence in bitumen.

The Commission for Environmental Cooperation, an environment body, was created in conjunction with the North American Free Trade Agreement. assessed all the published studies of water contamination and concluded that there was “scientifically valid evidence” that the waste ponds were leaching contaminants into groundwater. The analysis found that some research had concluded that the contamination reached Athabasca River, but scientists were still debating these findings.

Asked about the report, Coldbeck said her agency “does not have any evidence to suggest” that contaminated groundwater has reached the Athabasca River. In response to a question about health concerns, she said that the agency “is committed to ensuring that Alberta’s oil sands are developed in a safe and responsible manner,” and referred questions to Alberta Health, the province’s public health agency.

To deter birds from landing on the toxic Syncrude tailings pool, workers use noise-making and scarecrows. Officials have acknowledged that these ponds can leach chemicals into the groundwater but the effects are still disputed.

Multiple requests for comment were not answered by a spokesperson from Alberta Health.

A spokesperson for the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers declined comment to this article. She pointed instead to reports that the group has published on its website. engagement with Indigenous communities and on greenhouse gas emissions.

Nevertheless, Fort Chipewyan’s 2009 and 2014 cancer surveys came back mixed results. Both showed higher than average rates of certain cancers, including those in the biliary tract. One study concluded that overall cancer rates were elevated. The other did not.

The most recent case of the bile duct cancer was diagnosed in 2017, when Rigney’s nephew fell ill. Warren Simpson battled the illness for two years, but died in November 2019.

Rigney blames the oil development for her nephew’s death and all the others, even as she acknowledges that there’s nothing to prove the connection. Simpson was, according to her, just the latest fragment of her life that industrialization took.

“The delta was such a vibrant place,” she said. “And they took it all away, I mean all.” She added, “What else is there to take?”

The global oil industry is increasingly under assault, and Canada’s tar sands, because of the developments’ high greenhouse gas emissions, are a prime target of climate activists. Many financial analysts believe the era is over for opening new mines because new tar-sands projects will require billions of dollar upfront.

Even if the production from the mines declines slowly or stays steady, their huge footprints will likely continue to grow for decades because companies have to continue to clear land in order to keep up production. It doesn’t matter whether land is lost or gained by a new mine.

The industry will have to decide what to do with the mines’ waste and how to pay to clean them up when they do start to decline. The provincial government secured $730 million from companies to help pay for the clean-up. However, that is not enough to cover the costs. While regulators’ official estimate of the current liability for Alberta’s mining industry is $27 billion, an internal report obtained in 2018 by Canadian journalists estimated clean-up costs of more than $100 billion. Although this includes coal mines they only account for a small fraction of the overall costs.

Over the years, the people of Fort McKay have discussed moving the entire community to their reserve at Moose Lake, about 40 miles northwest, to get away from the development—Alberta’s government recently agreed to restrict, but not prohibit, deep-extraction tar sands sites within a 6-mile buffer around the lake. Fort McKay will, for the moment, remain as it is.

L’Hommecourt said she is torn about whether she will remain here. “My heart is in the boreal forest,” she said.

Her kids want to leave, and she might too. More roads are being blocked as the mines get closer to the cabin.

Regulatory filings show that Imperial Oil plans eventually to reroute the creek that runs past her cabin to make way for its Kearl mine. If it did, the land that houses the cabin would be buried with land from other parts of the mine. A spokeswoman for Imperial, Exxon’s Canadian affiliate, declined to comment specifically on the filings, but said the company “has collaborative and unique relationship agreements with these local communities that provide mutual benefits.”

The cabin itself has been a symbol of L’Hommecourt’s resistance. It sits on an old trappers’ trail that Imperial’s workers began using about 10 years ago as an unpaved access road for exploration, marking it off with a “No Trespassing” sign. L’Hommecourt built her cabin in the middle of that road.

“I just said ‘I don’t care,’” L’Hommecourt said. “I’m gonna put my house right here and this is where it’s going to be.” When company workers come by, she said, “I just tell them, ‘turn around and go back, and if you have a problem with it, get your VP or whoever it is that you report to and then tell them to come and see me.”

No one has yet to show up.

The Fifth Crime is an ongoing series produced by Inside Climate News In collaboration with Undark and NBC, about the campaign to make “ecocide” an international crime. Continue reading here and here.